Latest News

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Beacon Hill Roll Call, April 15-19

Beacon Hill Roll Call, April 15-19

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Reyes takes helm of UMass flagship amid pro-Palestinian protests

AMHERST — On a Friday morning filled with music, ceremony and speeches by state leaders to inaugurate Javier Reyes as the 31st leader of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and the first Hispanic chancellor of the flagship campus, protesters...

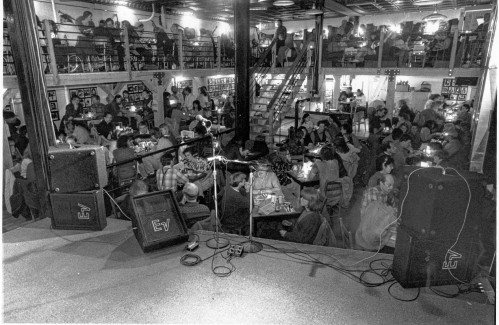

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

In late March, the fabled Iron Horse Music Hall, slated to reopen in mid May, was still a pretty raw construction site.Boards, pipes, boxes, and other materials were piled on the floors, along the walls, and on tables. Extension cords to power saws...

Most Read

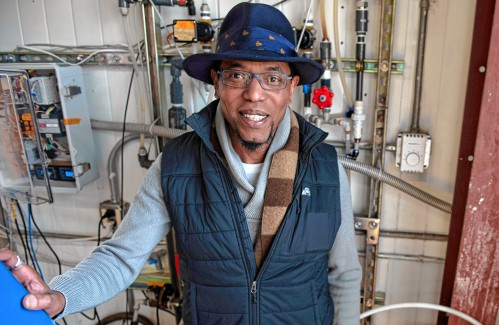

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Editors Picks

A Look Back, April 27

A Look Back, April 27

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

High schools: Furious fourth quarter rally falls just short for South Hadley boys lacrosse

SOUTH HADLEY – The South Hadley boys lacrosse team scored five unanswered goals in the fourth quarter to get within striking distance of Agawam (5-3), but the Tigers (4-5) comeback fell short in a 10-6 Valley League home loss on Friday afternoon.Solid...

Softball: Hampshire rallies from early deficit, slugs past Easthampton 10-4 (PHOTOS)

Softball: Hampshire rallies from early deficit, slugs past Easthampton 10-4 (PHOTOS)

2024 Gazette Girls Basketball Player of the Year: Ava Azzaro, Northampton

2024 Gazette Girls Basketball Player of the Year: Ava Azzaro, Northampton

Baseball: Chace Earle shuts down Easthampton in Hopkins Academy’s 13-0 win

Baseball: Chace Earle shuts down Easthampton in Hopkins Academy’s 13-0 win

Opinion

Charlene Galenski: Blake Gilmore, a strong candidate for Deerfield’s Selectboard

On May 6, Deerfield will have its annual election for local positions. Blake Gilmore is running as a candidate for Selectboard. Deerfield is facing some financially challenging times. Over the past few years, the town has voted to finance several...

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

Business

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

HOLYOKE — Like many people, Michael Garjian believes global warming is a pressing issue of our times.Unlike most, he’s putting his ideas for reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into practice — and at the same time bidding for a share of the $100...

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Among the many features that are part of 33 Hawley, the Northampton Community Arts Trust building that was finally completed in early January following 10 years of construction, there’s probably nothing more important to dancers than the floor of the...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Patricia Taylor

Patricia Taylor

Plymouth, MA - Pat, wife, mother, and grandmother, passed away on Saturday, April 20th after a long battle with cancer. Daughter of Valerian and Regina Latka, she leaves behind William, her husband of 54 years, her son Kevin and his par... remainder of obit for Patricia Taylor

Audrey McKemmie

Audrey McKemmie

Greenfield, MA - Audrey A. McKemmie of Greenfield and formerly of Amherst passed away on April 23, 2024, after a period of declining health. Born in Greenfield, December 12, 1930, she was the only child of John and Susie (Hayden) Kolink... remainder of obit for Audrey McKemmie

Donald E. Hooton

Donald E. Hooton

South Hadley, MA - South Hadley Donald E. Hooton, 91, passed away peacefully on Sunday, April 21 st , 2024, surrounded by his loving family. He was born in Holyoke to the late Eva (Utley) and Leonard Hooton. Donald moved to South ... remainder of obit for Donald E. Hooton

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

La Veracruzana, PHO-keh Bowl launch returnable container program

La Veracruzana, PHO-keh Bowl launch returnable container program

Amherst officials eye 2026 for 6th Grade Academy’s launch

Amherst officials eye 2026 for 6th Grade Academy’s launch

Amherst Regional School Committee proposes new budget that lowers assessments for towns

Amherst Regional School Committee proposes new budget that lowers assessments for towns

Is Steam Mill Road in Deerfield a public way? Land Court to decide as trial begins

Is Steam Mill Road in Deerfield a public way? Land Court to decide as trial begins

Around Amherst: Town cleanup day being organized for Saturday

Around Amherst: Town cleanup day being organized for Saturday

High schools: Ava Shea, Belchertown girls tennis get past South Hadley (PHOTOS)

High schools: Ava Shea, Belchertown girls tennis get past South Hadley (PHOTOS) Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever