More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Editor’s note: This story will be updated.AMHERST — More than 130 people were arrested on the University of Massachusetts campus Tuesday night after those who set up a pro-Palestinian encampment on the South Lawn of the Student Union refused to...

Sharing a few notes: High schoolers coaching younger string players one on one

AMHERST — Carefully holding and balancing his violin, 12-year-old Heedo Noh, a Fort River School sixth grader, gets a suggestion for positioning the bow so it runs straight across the strings as he practices G.F. Handel’s “Chorus from Judas...

Most Read

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

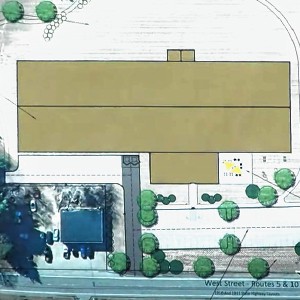

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Editors Picks

A Look Back, May 8

A Look Back, May 8

Guest columnist Cathy McNally: Northampton School Committee standing up for children

Guest columnist Cathy McNally: Northampton School Committee standing up for children

Karen Gardner: We all deserve a break

Karen Gardner: We all deserve a break

The Beat Goes On: A trombone celebration in Holyoke, Lord Russ shifts gears, and the Hampshire Young People’s Chorus turns 25

The Beat Goes On: A trombone celebration in Holyoke, Lord Russ shifts gears, and the Hampshire Young People’s Chorus turns 25

Sports

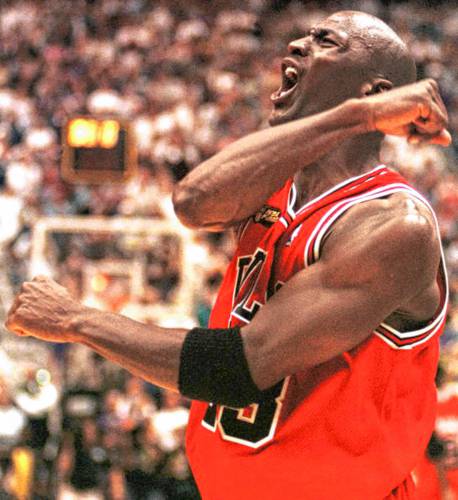

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

Just days after UMass forward Matt Cross announced his transfer to SMU – the fourth player to transfer away from the program this offseason – the Minutemen finally added their first piece to the 2024 roster on Tuesday night.Bryant’s Daniel Rivera...

Opinion

Guest column: Serving educational needs shouldn’t be ‘aspirational’

The School Committee recently passed a level services budget requiring an increase in its share of the city’s budget. My colleagues and I voted 8-1 — with the mayor abstaining — to pass this budget. We did so because we understand the challenges...

My Turn: Gaza and lies

My Turn: Gaza and lies

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Jennifer Dieringer: Budget must serve whole city

Jennifer Dieringer: Budget must serve whole city

Business

Area property deed transfers, May 2

AMHERST Faheem Ibrahim Lt and Faheem Ibrahim to Nan Zhao and Zhihong Ni, 16 Arbor Way, $738,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 1, $218,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 2,...

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

We’ve reached that point in the school year when it is actually painful (I mean physically painful) for me to leave my yard in the morning. May is the true month of the reawakening and blooming of Nature’s splendor and last week she was in full...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Wilford J. Morton, Jr. Belchertown, MA - Wilford J. Morton, Jr., beloved husband, father, and friend, passed away peacefully on April 14, 2024, at the age of 85. Wilford was born on September 17, 1938, in Waltham, Massachusetts, to his p... remainder of obit for Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Gary L. Campbell

Gary L. Campbell

South Hadley, MA - Gary L. Campbell, 70, of South Hadley, passed away surrounded by his loving family on Wednesday, May 1, 2024, in Sarasota, FL. Born in Holyoke, Gary was the son of the late Doris (Burnett) and John Campbell. He spent ... remainder of obit for Gary L. Campbell

Joyce Marion Orzel

Joyce Marion Orzel

Easthampton, MA - It only makes sense that the word "joy" sits at the beginning of her name. Joyce Marion Orzel passed away on April 25, 2024. Bringing joy to the everyday was her superpower. She was born in Holyoke on January 26, 1946... remainder of obit for Joyce Marion Orzel

Area property deed transfers, May 9

Area property deed transfers, May 9

Solar project to top docket at Westhampton Town Meeting on Saturday

Solar project to top docket at Westhampton Town Meeting on Saturday

Easthampton to use built-up reserves to help cover $57.1M budget next year

Easthampton to use built-up reserves to help cover $57.1M budget next year

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Fuller fends off challenge, wins 10th term on Chesterfield Select Board

Fuller fends off challenge, wins 10th term on Chesterfield Select Board

School assessment, electricity program among items on Pelham Town Meeting docket

School assessment, electricity program among items on Pelham Town Meeting docket

Easthampton native named Whately town administrator

Easthampton native named Whately town administrator

High schools: Ana Growhoski records 100th career hit in Easthampton softball’s win over East Longmeadow

High schools: Ana Growhoski records 100th career hit in Easthampton softball’s win over East Longmeadow Softball: Willow Hicks, Angela Magyar power Gateway past Amherst 8-1

Softball: Willow Hicks, Angela Magyar power Gateway past Amherst 8-1 Boys volleyball: Carey twins help power Frontier past Belchertown in straight sets (PHOTOS)

Boys volleyball: Carey twins help power Frontier past Belchertown in straight sets (PHOTOS) Baseball: Smith Academy edged by Logan Moore, Mohawk Trail in 1-0 loss (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Smith Academy edged by Logan Moore, Mohawk Trail in 1-0 loss (PHOTOS) Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

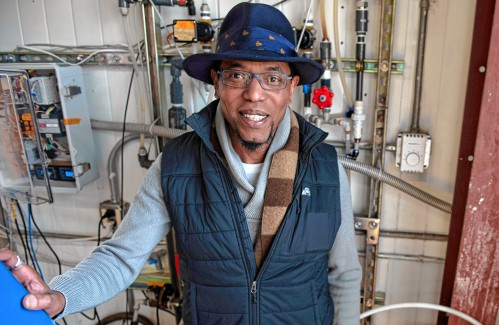

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city  Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley

Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier

Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier