My Turn: When volunteer lawyers saved us from Prohibition

| Published: 12-04-2023 4:20 PM |

Today, Dec. 5, 2023, is the 90th anniversary of a remarkable — and rarely remarked upon — episode in American history, having enormous consequences in law, in commerce, in families and in culture. More remarkable was its path, perhaps the best-kept secret in American constitutional law.

On this date in 1933, a constitutional convention in Utah voted to ratify the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, repealing the 18th Amendment and thus ending the Prohibition era. The convention’s proceedings were broadcast on the radio; when the vote was announced, a cheer could be heard from coast to coast.

It was a surprise to no one that the public was ready to heave Prohibition into the dustbin of history. Indeed, within days leading up the Utah vote, our state Legislature enacted a bevy of new laws to go into effect once federal barriers were out of the way.

That the amendment repealed a previous one is an anomaly that might make a good “Jeopardy!” question, but the real story is how, not why, it happened.

Article V of the U.S. Constitution provides that an amendment may be ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states or by “conventions in three fourths thereof.” Every amendment had been ratified by legislatures. Advocates for repeal saw that path as futile, as state legislatures were dominated by rural, fundamental interests, who were not about to yield to demon rum. The Supreme Court’s decision in Baker v. Carr, mandating proportional representation in statehouses, would not become law for another 30 years.

“Conventions?” Who would organize them? Where would they be held? How would delegates be chosen? Who would preside? Would debate be allowed? No state had any laws governing how it would respond if Congress proposed an amendment and was calling for ratification by conventions in the states.

Enter an amazing committee of lawyers, operating as volunteers and calling themselves, appropriately, the Voluntary Committee of Lawyers (VCL). They had organized in 1927 for the purpose of promoting debate within local bar associations about the criminalization of commerce in alcohol, as misgivings about it were typically whispered.

During the 1932 contest for the presidency, both the incumbent, Herbert Hoover, and the challenger, Franklin D. Roosevelt, made little mention of the issue, but enough to make it clear that a vote for Roosevelt was a vote for repeal, and a vote for Hoover was a vote for the status quo.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

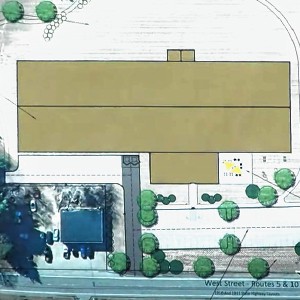

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

FDR won in a landslide. At the same time a dozen states passed voter initiatives repealing their state prohibition laws. (Massachusetts voters, with 63.8% support, had repealed ours in 1930.) The election of 1932 showed unambiguously that the nation was ready to ditch national prohibition. The lame-duck Congress proposed a repeal amendment, tossing ratification to state conventions.

By this time the VCL was ready. For several years they had been assiduously developing a model statute for adoption in the states, addressing the organizational questions. The model was almost universally adopted, in one form or another.

The most brilliant feature of the VCL-drafted law was how delegates to the convention were to be chosen. To ensure the vote would be “truly representative,” all candidates had to declare whether they were “wet” (for repeal) or “dry” (against repeal). Thus the final selection of delegates perfectly mirrored the preferences of voters as expressed in the privacy of a voting booth, where whispering was unnecessary.

Thanks to the legal infrastructure provided by the VCL, delegates were elected, conventions were held, and votes were taken in less than 10 months, second only in ratification time to the 26th Amendment (lowering the voting age from 21 to 18), adopted by the requisite 38 states in slightly over three months in 1971.

That the Constitution can be amended by voters, not only elected representatives, remains an underappreciated feature of American democracy. The contributions of the volunteer lawyers similarly remain underappreciated. “Search all the parks in all the cities,” G.K. Chesterton observed, “and you’ll find no statues of committees.” Alas.

Dick Evans is a Northampton lawyer.

Guest column: Serving educational needs shouldn’t be ‘aspirational’

Guest column: Serving educational needs shouldn’t be ‘aspirational’ My Turn: Gaza and lies

My Turn: Gaza and lies Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know