Columnist Razvan Sibii: Immigration myths: Part 1 — The ‘brokenness’ of the system

| Published: 01-16-2023 5:24 PM |

For more than two years now, my MO for this column has been this: I pick a topic related to incarceration or immigration that I think is important and interesting, I research it, I interview experts and people affected by the issue, and then I write the column.

At the beginning of this new year, however, I’ve decided to take a short break from these deep-dives and instead remind myself and my readers of the red thread that underscores many of my columns: The field of immigration is riddled with misconceptions, disinformation and outright myths that cause unnecessary suffering to some and make others into fearful angry xenophobes.

In this column and a few more after it, I will review some of the most harmful myths plaguing Americans’ understanding of who the undocumented immigrants are, how they got to be here, and what the current situation at the southern border is. In addition to reviewing some of the information that I’ve used in my previous columns, I will also be drawing on 21 interviews that I’ve conducted in the past month, by Zoom, phone and email, with representatives of 19 immigrant rights organizations from around the country.

While many, if not most, Americans agree that the U.S. immigration system is “broken,” what they’re usually thinking of is the failure of the system to deliver their desired final outcome: either higher acceptance rates and amnesty for undocumented immigrants or lower acceptance rates and the interdiction of undocumented immigrants.

The immigrant rights people whom I recently spoke to, however, have something else in mind when they talk about the immigration system as being “broken”: its unnecessary complexity, its discouraging difficulty, its maddening arbitrariness and prejudice, and its hopeless inadequacy and inefficiency. In other words, the system doesn’t do anything particularly well, other than making everyone involved (immigrants, lawyers, judges, border guards, NGOs and immigration scholars) utterly miserable.

“Immigration law is one of the most complex, baroque and outdated areas of American law. I’ve heard it compared to tax law,” Bonita Gutierrez, a founding member of Open Immigration Legal Services in Oakland, California, told me. “Immigration is governed by three agencies under the Department of Homeland Security, and they all have their own written and unwritten rules. They’re not things you can figure out from first principle. You know them by being connected with other immigration lawyers who have been doing this for longer than you so that you can ask them, ‘How does this work?’ Because you can’t read about them anywhere. And then there’s the immigration court system, the fourth agency that is under the Department of Justice, separate from the DHS. They’re very, very behind. They’re understaffed. They have a rotating cast of staff. It’s a very difficult job that really burns folks out. So nobody has institutional knowledge there.”

If it’s that hard for an immigration professional to figure out how things work, imagine what it’s like for an immigrant who is traumatized, doesn’t speak English, and is perhaps not literate in any language. And yes, many American citizens deal with these challenges every day in the country’s regular criminal courts. But here’s what separates immigrants from other people forced to plead their case in front of impatient and stressed-out authorities: Immigrants are not guaranteed access to an attorney.

If they have no money and are not lucky enough to have their case picked up by a lawyer employed by a non-profit organization or doing pro bono work in the weekends, they’re expected to make sense of Americans laws and all those agency rules, written and unwritten, on their own — and do it quickly, too. This applies even to unaccompanied minors who find themselves in front of an immigration judge.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

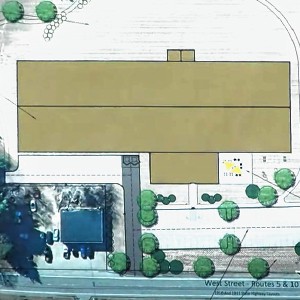

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

“In 2012, I saw for the first time in court a little kid defending himself,” said Claudia Abasto of LATINAN, a San Francisco-based organization that provides legal immigration services. “It blew my mind. Also in 2012, I heard a judge say that a 4-year-old is perfectly capable of understanding what is happening in court, that they can provide their name and the information that they need.”

And even when refugees are able to get legal representation, they remain at the mercy of a highly capricious adjudication system. The laws regulating the granting of asylum haven’t changed in decades, but their application varies wildly across the years, across immigration facilities, and even across the country’s cadre of immigration judges.

For example, according to a 2018 Southern Poverty Law Center report, some judges in the Deep South deny close to 100% of the requests for asylum that they hear, while some judges in Miami only deny about half the requests that they get. In one notable case from 2016, two brothers with the same story of persecution were handed out starkly different decisions by judges theoretically working with the same legal protocols.

The American immigration system is indeed broken. But so is our understanding of it, and that guarantees that policy-makers continue to operate under misguided pressures and unrealistic expectations. Next month’s column will map out other pernicious myths that get in the way of genuine immigration reform.

Razvan Sibii is a senior lecturer of journalism at UMass Amherst. He writes a monthly column on immigration and incarceration. He can be contacted at razvan@umass.edu.]]>

Guest column: Serving educational needs shouldn’t be ‘aspirational’

Guest column: Serving educational needs shouldn’t be ‘aspirational’ My Turn: Gaza and lies

My Turn: Gaza and lies Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Pride and prejudice Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know