Book Bag: ‘When the World Didn’t End’: Growing up in a cult, Guinevere Turner got a skewed view of the world

| Published: 09-08-2023 1:20 PM |

When the World Didn’t End

By Guinevere Turner

Crown

Reading Guinevere Turner’s affecting coming-of-age memoir, “When the World Didn’t End,” you’re left with one thought in particular: How did this woman endure years of emotional and psychological trauma and go on to forge a successful life and career as an adult?

Turner, an actor, screenwriter and director, spent the first 11-odd years of her life as a member of the Lyman “Family,” a doomsday cult led by U.S. musician and writer Melvin Lyman, who was convinced modern society was bankrupt and evil. He committed his flock to a life of isolation, away from “World People,” to await something better.

In fact, Lyman prophesied that on Jan. 5, 1975, life on Earth would end, but that members of his Family — scattered among different compounds in the U.S. — would be transported to Venus on a spaceship.

When the spaceship didn’t appear, Lyman said some of his followers were not spiritually ready for the journey. Turner, six years old at the time and living on a California compound with dozens of other children and adults, blamed herself for this failure: “I was certain it was me.”

That anecdote, which Turner relates at the beginning of her book, is just one of many instances in which she was full of self-recrimination as a child and then a young teen, convinced there was something wrong with her — when the real problems came from many of the adults in her life, who ranged from irresponsible to capricious to abusive.

Turner, 55, now splits her time between New York and Los Angeles. She wrote or co-wrote the screenplays for movies such as “American Psycho,” “The Notorious Bettie Page,” and “Charlie Says,” and she co-wrote and starred in the 1994 film “Go Fish,” a celebrated underground comedy about lesbian culture.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

In addition, Turner was a writer and story editor for Showtime’s “The L Word,” on which she played the recurring character Gabby Deveaux.

Turner will read from and discuss her memoir at Broadside Bookshop in Northampton Sept. 20 at 7 p.m.

She was born in Boston in 1968. Her 19-year-old mother, Bess, left college and joined the Lyman Family because she was alone (Turner’s birth father was never in the picture) and had nowhere to turn — something, Turner writes, that she didn’t learn until years later.

The Lyman Family believed children should be raised communally, so Turner spent most of her early years apart from Bess, living variously in the Fort Hill neighborhood in Boston — the original Lyman compound — and in Los Angeles, as well as on a farm in Kansas. (The Family also had a compound on Martha’s Vineyard.)

Writing about life on the Kansas farm, Turner sketches scenes that could come from a more pastoral era, with barefoot children shucking corn, weeding sorghum fields, and collecting chickens’ eggs; Turner also milked a goat.

At night there would be communal meals and time given to listening to music and watching movies on TV that were approved by Melvin Lyman. (The films were drawn from his “Lord’s List.”)

Turner, who based her memoir on extensive journals she kept while growing up — some passages are reproduced in the book — relates more disturbing aspects of the Lyman way of life, where “free love” was a mantra but men ruled the roost. Women and girls did all the cooking and housework, while the men sat around drinking and smoking (some took LSD).

Girls as young as 13 and 14 were “groomed” as future wives, she says.

“If a woman is really a woman,” Melvin Lyman once wrote, “than everything she does is for her man and her only satisfaction is in making her man a greater man.”

Lyman himself sired 13 children with six different women, Turner relates; one of his wives was Jessie, known as “The Queen.” The young Guinevere was bent on getting noticed by Jessie and winning her approval.

Turner finds some dark humor amid this weirdness, like the haphazard education the Lyman children received from the “erratic, often incoherent teachings of the adults who happened to be around.”

One history lesson, for instance, was based on examining the astrological charts of the U.S. presidents. Geography might consist of studying the places that Lyman, who died in 1978, had visited before he formed The Family.

Emotional support for children seemed fickle at best, and punishments could be cruel and arbitrary, like being locked in a closet, deprived of food, or being shunned for days by the community.

Yet young Guinevere felt a part of this world, and she was devastated when Jessie, who once had taken a shine to her, told her she didn’t love her anymore.

What came next was worse: Guinevere and her four-year-old half-sister, Annalee, were forced to leave The Family because their mother, Bess, and her boyfriend, identified only as FP, had left the group as well.

Going to live with Bess and FP created a whole new series of problems for Turner, then 11 years old, although again she’s able to relate some kernels of absurdist humor, such as when Bess registers her for sixth grade in the upstate New York town they’ve settled in.

“Where can we send for her school records?” asks an office secretary.

“Oh, the school burned down,” says Bess.

“I marveled at how easily my mother lied,” Turner writes. Bess also struggles for a moment to remember just how old her daughter is.

In fact, mother and daughter were strangers in many ways, making things worse when FP, a bullying, often violent man who expected subservience from all in the household, began sexually abusing Turner as she grew older. Turner felt she couldn’t share those horrors with her mother.

Bess remains a cipher in some ways. Years later, Turner asked her mother about the Lyman Family’s “spaceship to Venus” story, wondering how she could have believed anyone could live on a planet where temperatures reach 900 degrees Farenheit.

“It’s complicated,” Bess replied, then walked away.

Turner also had to learn the social cues and norms of living in this strange “outside world” that she’d always been warned about. Things got off to a rough start at school, Turner writes: “Within two weeks, I’d become the boys’ favorite person to make fun of.”

Some of them scratched out her name on her composition papers and tests and wrote “Guinaqueer” in its place.

What kept her going through years of tumult was reading and writing, says Turner, who graduated from Sarah Lawrence College, where she first came out as lesbian. “There have been points in my life when keeping a record of what was happening to me felt like the only power I had.”

In a few interviews this past spring, Turner said she’d contemplated writing about her childhood in the past but couldn’t bring herself to do it — not until after she wrote the screenplay for the 2019 film “Charlie Says,” about the women in the Manson Family.

“I’d spent my professional life pivoting away from questions about my childhood,” Turner told The New York Post. “But then when ‘Charlie Says’ came out, I was like, ‘No, it’s relevant.’”

In the end, “When the World Didn’t End” is a harrowing but moving story about how one woman overcame a childhood filled with trauma, loss, emotional isolation and more to find her way as an adult.

Turner will be joined by Valley author Andrea Lawlor at the Broadside Bookshop event on Sept. 20.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda

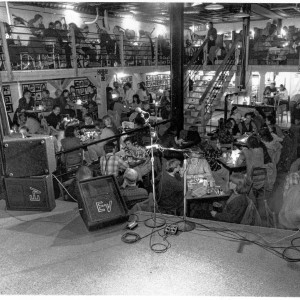

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15 The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor