Latest News

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

SUNDERLAND — Police located a cabin in the woods around Clark Mountain Road Thursday afternoon believed to belong to Taaniel Herberger-Brown, the suspect accused of murdering a man at 92 Chapman St. and storing his body in a plastic barrel for an...

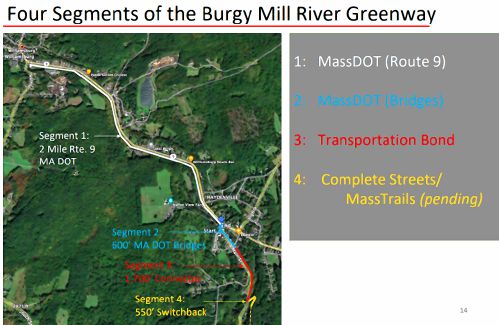

Haydenville residents resist Greenway trail plan, float alternative design

WILLIAMSBURG — With decision time nearing on the first section of the long-planned Mill River Greenway that will one day create a trail connection from Northampton to Williamsburg, a dispute over the project’s design through Haydenville’s residential...

Most Read

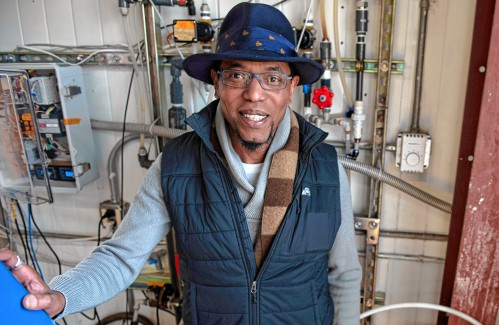

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Editors Picks

A Look Back, April 26

A Look Back, April 26

Photos: Roofing Rigger

Photos: Roofing Rigger

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

High schools: Ava Shea, Belchertown girls tennis get past South Hadley (PHOTOS)

Ava Shea continued her dominant season at No. 1 singles, helping the Belchertown girls tennis team to a 4-1 victory over South Hadley during independent action on Thursday at Mount Holyoke College.Shea notched a 6-0, 6-0 win over South...

Baseball: Chace Earle shuts down Easthampton in Hopkins Academy’s 13-0 win

Baseball: Chace Earle shuts down Easthampton in Hopkins Academy’s 13-0 win

2024 Gazette Ice Hockey Player of the Year: Cooper Beckwith, Amherst

2024 Gazette Ice Hockey Player of the Year: Cooper Beckwith, Amherst

Opinion

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

Both the Iranian government’s bombing of Israel and the Israeli government’s bombing of Iran are extremely perilous for the Middle East and the United States. That is why the dangerously one-sided U.S. congressional resolution, H.Res. 1143,...

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

Richard Clifford: We all need to look in a mirror first

Richard Clifford: We all need to look in a mirror first

Business

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

HOLYOKE — Like many people, Michael Garjian believes global warming is a pressing issue of our times.Unlike most, he’s putting his ideas for reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into practice — and at the same time bidding for a share of the $100...

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Among the many features that are part of 33 Hawley, the Northampton Community Arts Trust building that was finally completed in early January following 10 years of construction, there’s probably nothing more important to dancers than the floor of the...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Patricia Taylor

Patricia Taylor

Plymouth, MA - Pat, wife, mother, and grandmother, passed away on Saturday, April 20th after a long battle with cancer. Daughter of Valerian and Regina Latka, she leaves behind William, her husband of 54 years, her son Kevin and his par... remainder of obit for Patricia Taylor

Audrey McKemmie

Audrey McKemmie

Greenfield, MA - Audrey A. McKemmie of Greenfield and formerly of Amherst passed away on April 23, 2024, after a period of declining health. Born in Greenfield, December 12, 1930, she was the only child of John and Susie (Hayden) Kolink... remainder of obit for Audrey McKemmie

Donald E. Hooton

Donald E. Hooton

South Hadley, MA - South Hadley Donald E. Hooton, 91, passed away peacefully on Sunday, April 21 st , 2024, surrounded by his loving family. He was born in Holyoke to the late Eva (Utley) and Leonard Hooton. Donald moved to South ... remainder of obit for Donald E. Hooton

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Amherst Regional School Committee proposes new budget that lowers assessments for towns

Amherst Regional School Committee proposes new budget that lowers assessments for towns

Is Steam Mill Road in Deerfield a public way? Land Court to decide as trial begins

Is Steam Mill Road in Deerfield a public way? Land Court to decide as trial begins

Around Amherst: Town cleanup day being organized for Saturday

Around Amherst: Town cleanup day being organized for Saturday

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

Supreme Court seems skeptical of Trump’s claim of absolute immunity but decision's timing is unclear

Supreme Court seems skeptical of Trump’s claim of absolute immunity but decision's timing is unclear

Hatfield eyes reserves to cover unexpected spike in payments to Smith Vocational

Hatfield eyes reserves to cover unexpected spike in payments to Smith Vocational

High schools: Northampton boys tennis takes down Amherst in rain-shortened title-game rematch (PHOTOS)

High schools: Northampton boys tennis takes down Amherst in rain-shortened title-game rematch (PHOTOS) High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby

High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever