Latest News

Filling the need: Volunteer Fair returns, giving those seeking to donate their time a chance to see what’s out there

NORTHAMPTON — The partnership between HEC Academy and Western Massachusetts Rabbit Rescue began when a non-verbal student wanted to get involved with the community.Many of the volunteer opportunities offered by the therapeutic public day school for...

Amherst officials outline vision for Hickory Ridge: fire station, community center, affordable housing among options

AMHERST — A fire station, possibly combined with a new community center, or an affordable housing development, are among the concepts unveiled for the front portion of the former Hickory Ridge Golf Course on West Pomeroy Lane, the 150-acre, town-owned...

Most Read

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Editors Picks

A Look Back, April 29

A Look Back, April 29

Photos: The growing season begins

Photos: The growing season begins

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

Connor Pignatello: Seeing Messi in person again sparked childhood memories

FOXBOROUGH – When I was 8 years old, a Spanish friend of my dad gave me a present. It was a Lionel Messi FC Barcelona No. 10 jersey, with the club’s classic blue and red vertical stripes and the UNICEF sponsor across the front.That jersey was my most...

Opinion

Guest columnist Marietta Pritchard: Landlines and more in our parallel universe

Recent news reports and events have reminded me that my husband and I are living in a parallel universe. We use a landline and we read print newspapers, which are delivered to our house daily.I have and use a cellphone, but my husband does not. He...

Guest columnist Dr. Meghan Gump: Dear Patients — We hear you!

Guest columnist Dr. Meghan Gump: Dear Patients — We hear you!

Jenny Fleming-Ives and Peter Ives: Community must come together to fairly fund schools, city services

Jenny Fleming-Ives and Peter Ives: Community must come together to fairly fund schools, city services

Daniel Barker: Time for peace in Ukraine

Daniel Barker: Time for peace in Ukraine

Business

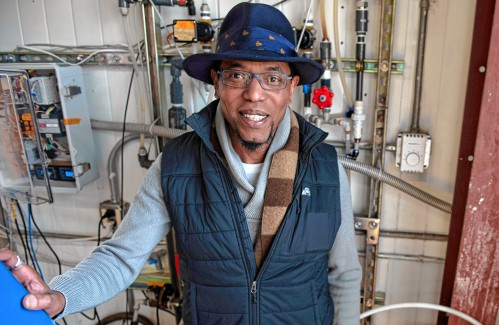

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

HOLYOKE — Like many people, Michael Garjian believes global warming is a pressing issue of our times.Unlike most, he’s putting his ideas for reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into practice — and at the same time bidding for a share of the $100...

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

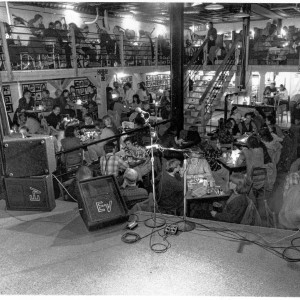

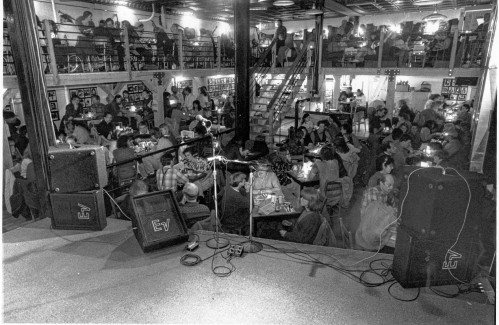

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

In late March, the fabled Iron Horse Music Hall, slated to reopen in mid May, was still a pretty raw construction site.Boards, pipes, boxes, and other materials were piled on the floors, along the walls, and on tables. Extension cords to power saws...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Elizabeth Merrill

Elizabeth Merrill

Elizabeth (Lisa) Merrill Northampton , MA - Lisa died peacefully in Hospice, attended by family, her longtime caregivers, and the wonderful staff at Linda Manor Assisted Living in Northampton, MA on April 15, 2024 at age 95. Lisa was bo... remainder of obit for Elizabeth Merrill

Mary F. R. Watson

Mary F. R. Watson

NORTHAMPTON, MA - Mary F.R. Watson, 77, formerly of Providence, R.I. , Boston, MA. and of Laurel Park in Northampton passed peacefully on Saturday, April 20, 2024. Friends of Mary may gather with her husband, Kevin Gilligan of Providenc... remainder of obit for Mary F. R. Watson

Mary J. Majeau-Koziol

Mary J. Majeau-Koziol

Mary J Majeau-Koziol Virginia Beach, VA - Mary 77, passed away peacefully on April 5, 2024. She was a wonderful person and will be deeply missed by her family and friends. To view her complete obituary and to offer condolences, please vi... remainder of obit for Mary J. Majeau-Koziol

Chance Encounters with Bob Flaherty: The coming of bees puts South Hadley man in high spirits

Chance Encounters with Bob Flaherty: The coming of bees puts South Hadley man in high spirits

Cannabis sales in Massachusetts top $1B for third straight year

Cannabis sales in Massachusetts top $1B for third straight year

Town election in Worthington features contest for Select Board seat

Town election in Worthington features contest for Select Board seat

Voters at Hadley Town Meeting to decide big capital projects on Thursday

Voters at Hadley Town Meeting to decide big capital projects on Thursday

Area briefs: Broad Brook Greenway parking; Northampton pickleball group to hold event; and more

Area briefs: Broad Brook Greenway parking; Northampton pickleball group to hold event; and more

Frontier Regional School students appeal to lower voting age

Frontier Regional School students appeal to lower voting age

Deerfield residents to decide personnel bylaw, tax bill at Monday’s annual Town Meeting

Deerfield residents to decide personnel bylaw, tax bill at Monday’s annual Town Meeting

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching High schools: Furious fourth quarter rally falls just short for South Hadley boys lacrosse

High schools: Furious fourth quarter rally falls just short for South Hadley boys lacrosse  Softball: Hampshire rallies from early deficit, slugs past Easthampton 10-4 (PHOTOS)

Softball: Hampshire rallies from early deficit, slugs past Easthampton 10-4 (PHOTOS) 2024 Gazette Girls Basketball Player of the Year: Ava Azzaro, Northampton

2024 Gazette Girls Basketball Player of the Year: Ava Azzaro, Northampton Guest columnist Lawrence Pareles: Make completing FAFSA form a high school graduation requirement

Guest columnist Lawrence Pareles: Make completing FAFSA form a high school graduation requirement Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more