Latest News

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

No contests on ballot for Willisamsburg election

No contests on ballot for Willisamsburg election

Contested races shaping up in Chesterfield

Contested races shaping up in Chesterfield

Granby Bow and Gun Club says stray bullets that hit homes in Belchertown did not come from its range

BELCHERTOWN — The president of the Granby Bow and Gun Club insists that stray bullets that hit two homes and a shed in the Turkey Hill area of town did not originate from the club’s long range.Club President Ryan Downing read a statement at the...

Change in federal drug classification could help cannabis shops

NORTHAMPTON — In the wake of the Justice Department’s proposal to reclassify cannabis as a less dangerous drug, dispensary owners say the change would help their business, especially on taxes.“The immediate impact would be for the government to treat...

Most Read

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Amherst council hears call to scale back Jones work

Amherst council hears call to scale back Jones work

Editors Picks

A Look Back, May 2

A Look Back, May 2

Photos: Special connection

Photos: Special connection

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

Boys tennis: Sixth grader Lee Ferguson key cog in PVCICS’ win over Belchertown, undefeated start to the season (PHOTOS)

BELCHERTOWN — Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School boys tennis coach Mike Locher has a Star Wars character assigned to each player on his team.After every match, he sends his players a game recap, along with a YouTube video of their Star...

South Hadley boys volleyball team making strides in first season as program

South Hadley boys volleyball team making strides in first season as program

2024 Gazette Boys Swimmer of the Year: Luke Giguere, Belchertown

2024 Gazette Boys Swimmer of the Year: Luke Giguere, Belchertown

Opinion

Jennifer Dieringer: Budget must serve whole city

I am the parent of a Northampton High School student. I have been fortunate enough to have had the capacity and time to be engaged in the schools my son has attended, serving on the PTO since he was at Bridge Street Elementary School. (Pro tip: If you...

Nancy E. Grove: Landlines are the best

Nancy E. Grove: Landlines are the best

Sage Cooper-Clermont: A well-deserved thank you for chain of help

Sage Cooper-Clermont: A well-deserved thank you for chain of help

Ken Rosenthal: Time to change direction on Jones Library

Ken Rosenthal: Time to change direction on Jones Library

Joshua Singer: Friends of the trails could use a hand

Joshua Singer: Friends of the trails could use a hand

Business

Area property deed transfers, May 2

AMHERST Faheem Ibrahim Lt and Faheem Ibrahim to Nan Zhao and Zhihong Ni, 16 Arbor Way, $738,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 1, $218,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 2,...

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda

It was the morning of April 16 and I was up early. It seems to be impossible for me to sleep late at this time of year because I am so excited about seeing the first birds of the season, but this particular morning was a little different. It was the...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Andre Nolet

Andre Nolet

Holyoke, MA - Holyoke- Andre E. Nolet, a resident of Holyoke, passed away at home on April 28, 2024 at the age of 74. One of six children to the late J. Leo Nolet and Rose (Roy) Harker, Andre was born in Holyoke on October 6, 1949. He a... remainder of obit for Andre Nolet

Marion Shea

Marion Shea

(1919 - 2024) NORTHAMPTON, MA - Marion Catherine (Osepowicz) Shea, of Northampton passed away at her home peacefully with family members and support by the nurses from the Hospice of the Fisher Home, Amherst, Massachusetts on Saturday, ... remainder of obit for Marion Shea

Ronald O'brien

Ronald O'brien

Northampton, MA - Ronald Paul O'Brien, 76, passed away peacefully at Cooley Dickinson Hospital after a brief illness. Born in St. Stephens New Brunswick, Canada, the O'Briens immigrated to the United States where Ronald grew up and atte... remainder of obit for Ronald O'brien

Services being held Thursday for Greenfield homicide victim

Services being held Thursday for Greenfield homicide victim

Former Chicopee superintendent sentenced to year probation for lying to FBI

Former Chicopee superintendent sentenced to year probation for lying to FBI

Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author Colson Whitehead to speak at UMass commencement

Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author Colson Whitehead to speak at UMass commencement

Healey expects $16B return on climate tech investment

Healey expects $16B return on climate tech investment

Glitz, glamour and all that jazz: ‘Chicago’ takes stage at Easthampton High starting Thursday

Glitz, glamour and all that jazz: ‘Chicago’ takes stage at Easthampton High starting Thursday

Girls lacrosse: Amherst stays undefeated, runs away from Granby for second win in as many days (PHOTOS)

Girls lacrosse: Amherst stays undefeated, runs away from Granby for second win in as many days (PHOTOS) Softball: Ella Schaeffer’s walk-off hit lifts South Hadley to 1-0 extra-inning win over Easthampton

Softball: Ella Schaeffer’s walk-off hit lifts South Hadley to 1-0 extra-inning win over Easthampton Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

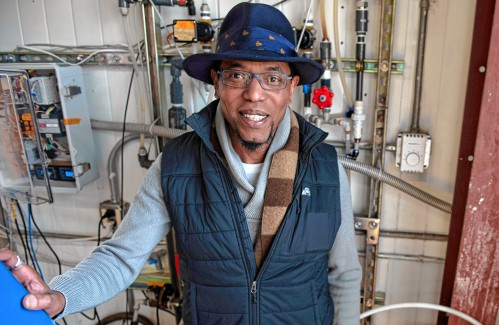

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city  Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

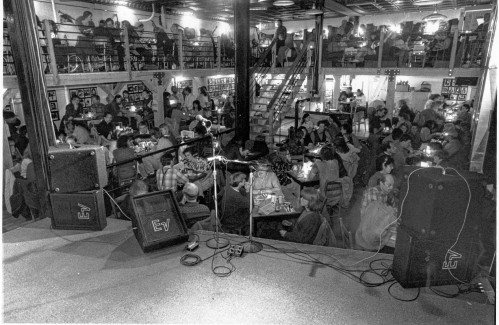

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15 Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week