Chalk Talk: When kids turn work in late: Navigating the tricky balance of deadlines and support for students

Nicole Godard is a district instructional coach and AP Literature & Composition teacher at Hampden Charter School of Science. CONTRIBUTED

| Published: 02-29-2024 2:20 PM |

It’s March again, which means that in many high schools a new semester is well underway. At the end of every grading period, the same conversation starts making the rounds in teaching circles, on social media, in the teacher’s lounge, all sharing a similar anecdote: “So-and-so just turned in work weeks after it was due!” “So-and-so finally decided to ask about their failing grade — too little too late!”

Each conversation is tinged with some outrage and even more desperation. As teachers, how do we make the kids care about their assignments? How do we protect our own boundaries when the onslaught of late work comes in? And, particularly for teachers of high school students, how do we handle the sinking feeling that we’re failing to teach our students some kind of important lesson about deadlines and timeliness?

There are no easy answers. Some schools have their own late policies enacted district-wide, while others leave teachers to create their own policies ranging from late penalties imposing rapidly decreasing maximum credit to fully non-negotiable deadlines. As an instructional coach, my early career colleagues often ask me about my late policy or what I think they should do about theirs, and my answer usually frustrates them. Well, it depends.

I encourage my colleagues to ask themselves a few questions when evaluating their gradebooks and their students’ work.

■What is this assignment for?

■What do I want this assignment’s grade to communicate to my student?

■Why do I think my student turned in this work late?

Is every assignment worthy of an appearance in the gradebook? Does every piece of classwork, bellringer, exit ticket, or class discussion require a grade? If it is a summative assignment, one that represents cumulative work and mastery of skills, what will this final grade tell me when I put it into the gradebook? Am I measuring content mastery or compliance? And finally — do I believe my students are failing to turn in work out of laziness? Defiance? Personal spite?

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

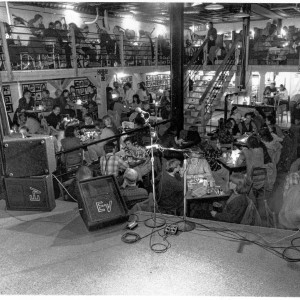

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Amherst council hears call to scale back Jones work

Amherst council hears call to scale back Jones work

Over the last decade of my teaching career, from middle school to high school, I’ve tried it all. I’ve staunchly refused assignments over a week late. I’ve taken off five points for every day past due. I’ve taken anything turned in up until the eleventh hour. Do I feel like I’ve figured it out? No — but here are a few things that I have.

Late work comes with its own natural consequences.

We’ve all missed a deadline, whether for paying a bill, filing taxes, or showing up for a doctor’s appointment, and we know well the profound anxiety that accompanies these missteps. Though seeing through a teenager’s affect can be difficult, our students feel the same way. Missed deadlines and piles of late work carry with them their own consequences — students feel stressed, they don’t benefit from our feedback on drafts, they have to cram their work into a sleepless night as the quarter comes to an end, and they are almost always unable to produce their best work. In the end, I often find that no late penalty is necessary — the circumstances of the assignment completion are penalty enough.

Students will do well if they can; they often just need help.

American psychologist Ross Greene said that “Kids will do well … when they can.” He urged psychologists, parents, and educators to reconsider whether a child was “just” lazy, or disinterested, or unmotivated. Rather, he argued that a child’s behavior is communicating a need that has not been met or a skill that has not been developed.

Our struggling student’s unmet needs (i.e., time to work, a context for their learning, a well-crafted assignment) and undeveloped skills (i.e., time management, self-regulation, executive functioning) create a perfect storm for unfinished work. As teachers, our job is to help mitigate those challenges to give them a chance to finish that learning. In my own school community, teachers offer daily study hall tutoring, after-school help, online office hours on Zoom, and Saturday school to provide students with secondary spaces to do work. I hold weekly “Get Stuff Done Hours” online with my students, offering a “body double” for my students who need another person present to keep them accountable and undistracted. While this doesn’t fulfill every student’s need, it does provide another access point for students who are struggling to complete their class work.

I don’t have to work miracles; I just need to have a system.

May no reader mistake me — I believe in boundaries and deadlines. But I also know our kids have sports, band, Boy Scouts, jobs, and a thousand other things that get between them and the work we assign them. And while I do not believe any of us are responsible for working miracles for our students who are overextended or underprepared, we are responsible for implementing a system that makes sense to our students. I tell my students that there’s a hard deadline for me at the end of every marking period, so in turn I need to establish my own deadlines to make sure I can complete my work on time. I model for my students the time management I expect them to develop, and I extend grace to my students when they struggle to navigate that system.

Life is pretty hard already; as we move into Semester 2, let’s work with our students to help make it easier for all of us.

Nicole Godard is a district instructional coach and AP Literature & Composition teacher at Hampden Charter School of Science.

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15 The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor