An exhibit to kvell over: Expansive new Amherst exhibit looks at the global impact of Yiddish

| Published: 10-27-2023 8:13 AM |

About five to six years ago, staff at the Yiddish Book Center began considering an expansive exhibit on Yiddish culture that would open in 2020 to mark the book center’s 40th anniversary.

The pandemic and a few other things prevented that from taking place. But three years later, that exhibit is now in place — and it’s one that’s been worth waiting for.

“Yiddish: A Global Culture” is the most expansive exhibition the Amherst center has ever staged, a sweeping exploration of modern Yiddish literature, theater, music, politics and more that flourished from the late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, linking communities from Warsaw to Vilna to New York to Buenos Aires.

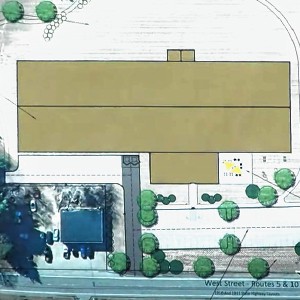

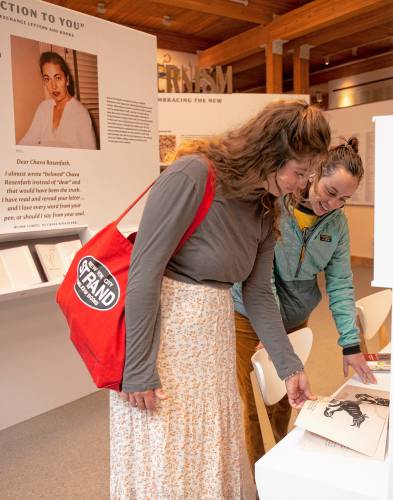

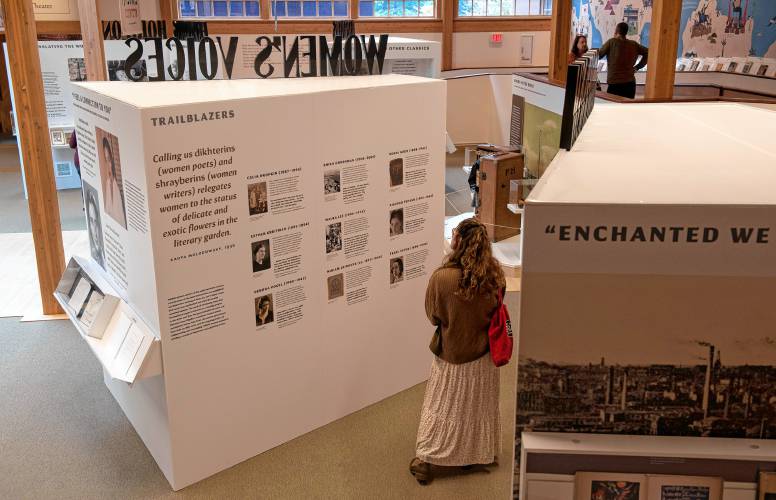

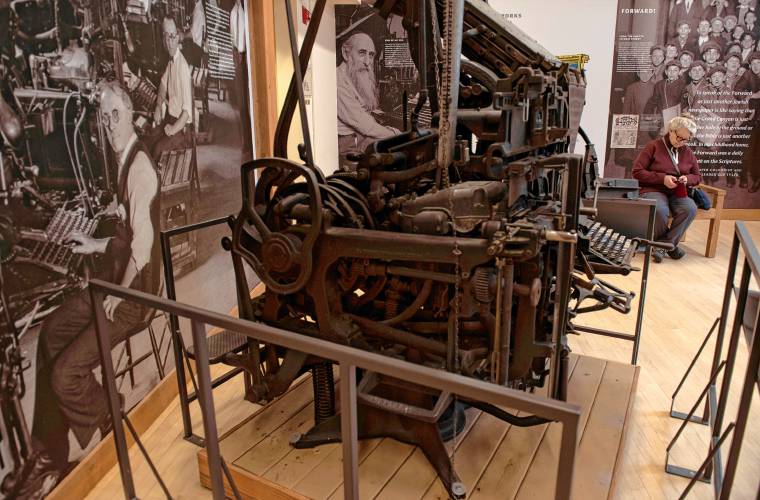

To accommodate some 350 objects, including rare books, photographs, theater posters, Yiddish typewriters, and other artifacts, the book center has reconfigured its main room, replacing a number of bookshelves with large kiosks and other displays.

Whereas most previous exhibits have been limited to one or two modest gallery spaces, “Yiddish: A Global Culture” occupies a much larger area, with themed sections such as women artists and Yiddish theater, and will now be a permanent part of the building. Most of the materials come from the center’s own collections.

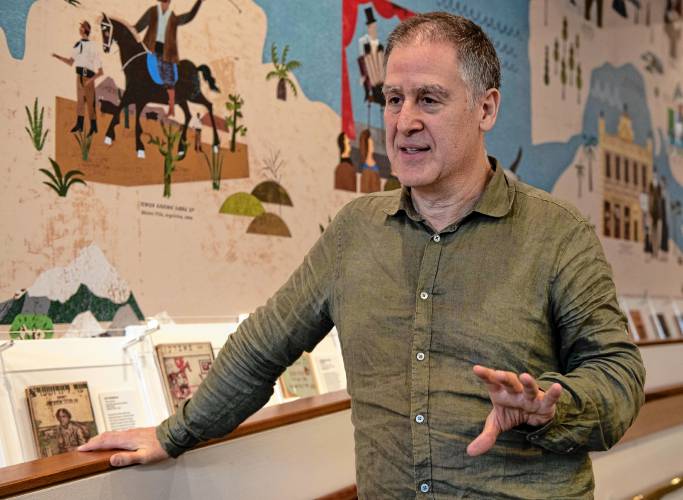

“We really needed the space to do justice to the subject,” said David Mazower, the exhibit’s chief curator; he’s also the book center’s research bibliographer and editorial director.

“Even with that, we had to make some tough decisions on what to leave out,” he said.

But what’s included is certainly rich, both from a broad historical perspective and in terms of personal stories.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

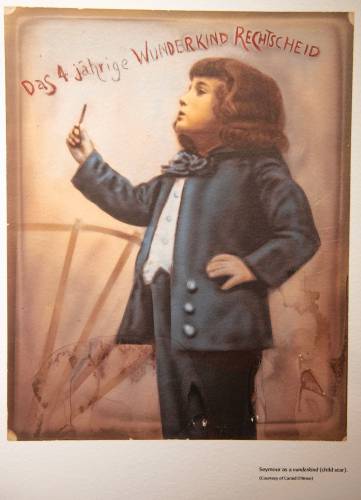

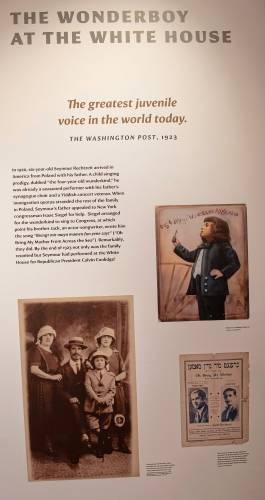

There’s Seymour Rechtzeit, for instance, a child singing prodigy who came to America from Poland with his father in 1920. Strict new U.S. immigration quotas left other family members stranded in Europe, so a New York congressman helped arrange for Rechtzeit, perhaps nine years old then, to perform for Congress.

The wunderkind, as exhibit notes put it, sang “Brengt Mir Mayn Mamen fun Yene Zayt” (“Oh Bring My Mother From Across the Sea”), a song written by an older brother, and so impressed members of congress (and later President Calvin Coolidge) that Rechtzeit’s other family members were able to come to the U.S. by the end of 1923. (Later changing his last name to Rexite, the singer had a highly successful career as an adult, too.)

Among a display of books that includes Yiddish versions of the first Harry Potter novel and “The Old Man and the Sea” (“Der alter un der yam”), there’s work by Yoyne (Jonas) Kreppel, who wrote a series of Yiddish detective novels in the early 20th century. The main character, Max Spitzkopf, was known as the “Viennese Sherlock Holmes.”

Mazower, who grew up in England, has a number of personal connections to the exhibit. His great-grandfather, Sholem Asch, born in Poland in 1880, was a prominent Yiddish playwright and novelist in the first part of the 20th century whose plays were staged in Germany, the U.S., and a number of other places; he also wrote for Yiddish newspapers in the U.S.

Having written widely about Yiddish culture himself, Mazower says the exhibit’s focus on Sholem Asch, Seymour Rechtzeit, and other cultural figures is designed to show that Yiddish was always more than simply a language spoken in Central and Eastern Europe and different enclaves, like New York.

“The idea is to kind of flip the switch on what people might have thought … and make the case for Yiddish as a really unique global culture,” he said. “In literature, in theater, in music, it’s something that can stand on its own, in many parts of the world.”

But as Yiddish was also the language of everyday life for millions of Jews, Mazower noted, many Yiddish speakers felt particularly close ties to Yiddish artists. Yiddish theater, especially, developed “an incredibly devoted following,” he said, notably among working class Jews.

Part of that stemmed from the sometimes ribald and colloquial topics that were presented on stage by Yiddish dramatists, who were known for their “incredible chutzpah and drive,” as Mazower puts it.

And when Sholem Aleichem, perhaps the most revered Yiddish writer of his day — “Fiddler on the Roof” is based on some of his stories — died in New York in 1916, as many as 250,000 people lined the streets to watch as his horse-drawn casket was transported from his Bronx home to a cemetery in Queens, the exhibit says.

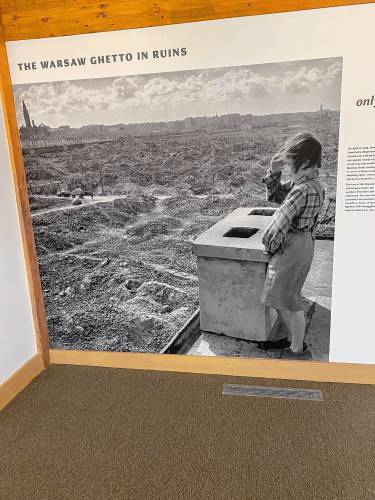

“Yiddish: A Global Culture” also looks at how Nazi Germany destroyed much of that vibrant Yiddish world, as most of the 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers.

A huge photograph symbolizes that loss, an image of a vast ocean of rubble in Warsaw taken during or shortly after WWII. It’s all that remains of the Warsaw Ghetto after the Nazis razed the buildings following a 1943 uprising there. A young girl, wearing mismatched, oversize shoes, stares out at the desolate scene.

Yiddish also began to disappear after the war in places like the U.S., Mazower notes, as later generations of Jews grew up speaking the language of their adopted countries. In Israel, Hebrew was the official language; Yiddish was considered best forgotten.

One of his grandparents spoke Yiddish, Mazower says, but he only learned the language as an adult after meeting some older Yiddish speakers, such as Harry Ariel, a Polish native who was active in Yiddish theater in London after WWII (his story is included in the exhibit).

Yet the Yiddish legacy has been felt in other ways. One exhibit section features digital portraits of well-known figures whose lives connected with Yiddish, sometimes in surprising ways — like Marlon Brando and Salma Hayek, of all people. It turns out both studied with Stella Adler, a legendary Yiddish actor turned influential acting teacher.

Then there’s a guy named George Gershwin (born Jacob Gershwin in Brooklyn, New York), who as a young man tried to get a job as a composer in Yiddish theater. He was turned down and instead went on to write some noteworthy tunes such as “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Another Yiddish mentor was I.L. Peretz, a writer and playwright who ran a popular salon out of his Warsaw apartment in the late 19th and early 20th century. Many aspiring writers would go there to try and get his blessing for their work.

“It was said his door could make or break you,” Mazower said with a laugh. “There are a lot of stories … of writers standing outside his apartment, trying to work up the nerve to ring the bell.”

Peretz’s apartment was “such a magical place,” Mazower added, where writers often congregated, that he and his exhibit co-designers recreated Peretz’s main room, including a style of wallpaper that matches the pattern they saw on an old photograph of the room.

This specially crafted space is filled with portraits of the many writers who first found their footing at Peretz’s apartment, including Sholem Asch, Mazower’s great-grandfather.

“Yiddish: A Global Culture” also makes the case that Yiddish is not just about the past. The Amherst book center continues to spearhead varied efforts to introduce the language and its cultural history to new students and scholars, and to preserve the stories and memories of older Yiddish speakers from around the world.

That’s a vital mission, Mazower says: “Yiddish has to be part of the modern Jewish story. Otherwise that story’s incomplete.”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley

Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses