State is a ‘pioneer’ in life sciences, but experts say more help needed to maintain industry leader status

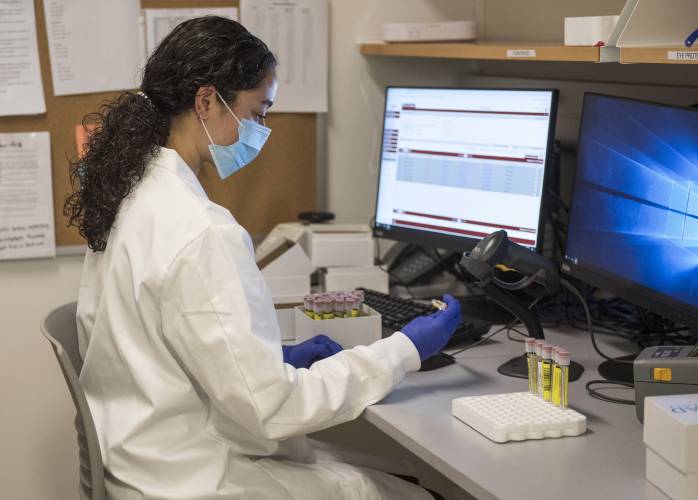

University of Massachusetts Amherst biology major logs COVID-19 test samples in the accessioning room of the Institute for Applied Life Sciences Clinical Testing Center, or ICTC, in 2021. GAZETTE FILE PHOTO

| Published: 11-26-2023 3:00 PM |

Laura Kleiman was running a research center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute when her mother was diagnosed with cancer.

In exploring potential treatment options, Kleiman said she discovered that repurposing drugs — particularly generic ones that are already widely available — could be key to developing affordable cancer treatments.

Kleiman then quit her job at the institute and launched Reboot Rx, a nonprofit health tech startup that aims to fast-track cancer treatments.

Reboot Rx is just one startup that is part of Massachusetts’ “vibrant community” of research.

“It’s clearly one of the most exciting regions of the country, if not the most exciting to be able to do research and develop new treatments for patients,” Kleiman said.

Reports show targeted and intentional investments into Massachusetts’ life sciences sector make the state a leader in the industry. But experts say continued leadership depends on help in boosting startups over logistical hurdles like high real estate costs and transportation woes.

Massachusetts’ biomanufacturing workforce experienced a year-over-year growth of 6.3%, outpacing New York and California, according to MassBio 2023 Industry Snapshot.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

Services being held Thursday for Greenfield homicide victim

Services being held Thursday for Greenfield homicide victim

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Area property deed transfers, May 2

Granby Bow and Gun Club says stray bullets that hit homes in Belchertown did not come from its range

Granby Bow and Gun Club says stray bullets that hit homes in Belchertown did not come from its range

3-unit, 10-bed house in backyard called too much for Amherst historic district

3-unit, 10-bed house in backyard called too much for Amherst historic district

“While we all know biotech experienced a period of cooling after a red hot few years, our workforce growth, lab space expansion, large share of overall national [venture capital] investments, and strong government relationships make me hopeful for a strong 2024 and beyond,” MassBio CEO and President Kendalle Burlin O’Connell wrote in a statement.

Boston University Questrom School of Business Professor Avi Seidmann said Massachusetts has been a “pioneer” in life sciences.

“We integrate academic excellence with world class hospitals,” Seidmann said. “We have an ecosystem which has been extremely successful.”

Over the last 10 years, graduates from biotech-related academic programs increased by over 50% and master’s degrees increased by 100%, according to the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center.

The National Institutes of Health granted $1.48 billion to Massachusetts higher education and research institutes and hospitals received 51% of all NIH funding in 2022, according to the MassBio report.

In addition to support from universities and hospitals, NanoView Biosciences co-founder David Freedman said large companies in the state are also beneficial for startups.

“Having that network of companies in the general vicinity is really valuable,” he said. “They can get training, or they can potentially be customers or collaborators with your startups.”

Freedman said Massachusetts has made it a goal to “create a life sciences hub here.”

“I think it’s been a very deliberate process in Massachusetts,” Freedman said. “Now it feels like it’s just a natural part of the ecosystem here, but I think that’s because people continue to emphasize it.”

In 2008, former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick signed a 10-year, $1 billion investment in Massachusetts’ life sciences industry.

The MLSC — governed by a board of state officials and industry leaders — was given the responsibility of expanding the life sciences industry through innovation infrastructure, targeted capital programs and tax incentives facilitating job creation.

Freedman said his company participated in the MLSC’s internship program which gives startups funding to hire interns.

“It helped, especially in the early stage when we had no money,” he said. “It helped supplement the work we were doing.”

Kleiman said she also participated in the internship program which allowed her nonprofit to “tap into the young talent in the state” and took part in the Massachusetts Next Generation Initiative which provides leadership coaching and networking.

Seidmann said other states like New York, which also has prestigious hospitals, are investing more money in biotech startups in an effort to “mimic” Boston’s success.

In 2022, NIH allotted roughly $157.8 million more in aggregate funding to New York, but Massachusetts received $295 more in per capita funding.

Although New York has access to more monetary funding, Boston University Questrom School of Business Lecturer Patrick Abouchalache said it does not put Massachusetts at a disadvantage.

“[The industry] is still more supply driven from the talent, from the research, from the data, than the capital side,” he said.

Industry investor Bruce Booth said over the past couple of years, the number of new startups in the industry in Boston has gone down, leaving the city with surplus real estate space designed for the industry.

“Today, we actually have more space than the ecosystem can sufficiently handle right now,” Booth, who is a partner at Atlas Venture, said. “I think it’s gonna take a few years to grow into all of the available space options.”

Twelve million square feet of space is expected to be completed by 2024, with over nine million square feet vacant for prospective tenants, according to a Cushman & Wakefield report. Roughly 36% is pre-leased.

“If supply is coming on faster than you demand from the startup level, you’re going to have the same types of vacancies that we’ve had through the pandemic for commercial real estate downtown Boston,” Abouchalache said.

High real estate costs have made sustaining young talent more difficult, Seidmann said.

“When you’re a young scientist, real estate is a big part of your monthly expenditure,” he said. “The government should find ways to help companies defray those costs for the academics.”

Seidmann said Massachusetts can support startups by choosing sub-segments of biotech to specialize in and increasing the number of incubators and accelerators in the state.

Kleiman said her startup would appreciate support from the state to bolster her startup’s policy initiatives.

“I think having a line of communication would be helpful,” she said. “It would be really helpful to have a conversation with anyone from Massachusetts who might be able to help drive those initiatives forward.”

Booth said improving the state’s transportation infrastructure to improve worker’s commutes would be beneficial for the industry at large.

“It is incredibly challenging and certainly one of the biggest impediments to the continued growth and acceleration,” he said. “That’s a space where some more thoughtful urban planning and economic development such would be very welcomed by the biotech ecosystem.”

Despite these concerns, Booth said Massachusetts’ “huge concentration” of companies sets it apart from other states and “enables risk taking.”

“There’s so many companies, so if your science in your company doesn’t work, you can typically move to another company relatively quickly, because there’s so many other opportunities,” he said. “It enables people to be bolder about the kinds of science and medicine that we would like to do.”

Lindsay Shachnow writes for the Gazette from the Boston University Statehouse Program.

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue Amherst council confirms Gabriel Ting as police chief

Amherst council confirms Gabriel Ting as police chief Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city