New reports inform emissions-fighting debate: Forests play a key role

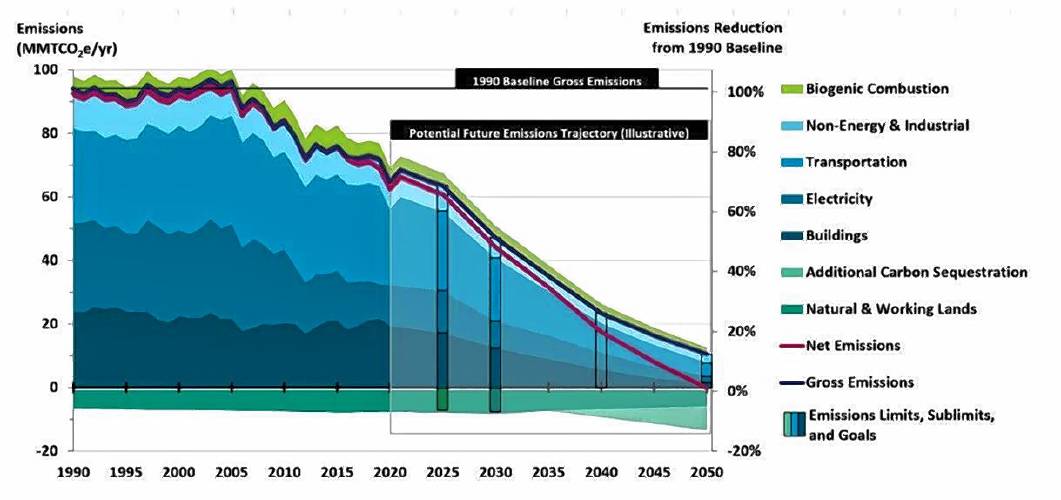

Massachusetts has committed to achieving declining greenhouse gas emission targets, including a minimum 85% reduction (compared to 1990 levels) by 2050. Climate Forestry Committee report

| Published: 01-04-2024 9:53 AM |

BOSTON — A pair of reports made public this week illustrate the variety of efforts that are underway to position Massachusetts to live up to its legal requirement to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

In addition to a minimum 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, Massachusetts law requires the state to reduce emissions by at least 75% by 2040 and at least 85% by 2050. To get there, the state needs to scale back emissions from power generation, as well as from transportation, building heating and the rest of the economy.

Progress on that front was announced Wednesday morning, when the developers behind the Vineyard Wind 1 project said the state’s first offshore wind project had delivered its first green electrons to the grid.

Tag-along policies like carbon sequestration are expected to help the state get the rest of the way to net-zero emissions by 2050. That was the focus of a new report released by the Healey administration Wednesday looking at how the state and private forest owners can deploy climate-oriented forest management practices.

The Climate Forestry Committee’s report, assembled by a panel of 12 scientific experts, urges the state to sharpen its land management focus on climate change mitigation and adaptation and contains recommendations to the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs.

“Forests are an essential component of the earth’s operating system and will be affected by climate change as well as play a vital role in addressing its causes and adapting to its effects,” the report said.

“Globally, forests have the capacity to remove substantial amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, serving as partial mitigation for GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions that cannot otherwise be eliminated. This includes forests in Massachusetts, which currently store regionally significant quantities of carbon and can continue sequestering and storing substantially more, with climate change potentially improving growing conditions through mid-century.”

The committee focused its recommendations around the idea that forest management practices fall along a spectrum from the most passive, hands-off approach — where nature takes it course — to active management, where interventions are targeted to advance specific forest conditions. While members of the climate committee agreed that carbon storage is greatest in older forests, the report concluded that “the state should allow forests to grow old while balancing goals for active management.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

It also recommended strategies for pursuing active forest management in a climate-focused manner.

“The Committee generally agreed that passive management would confer greater increases in carbon stocks compared with active management. That is, allowing forests to grow and age through passive management is typically the best approach for maximizing carbon storage,” the report said.

“However, there may be exceptions to this, and the CFC recognizes that the Commonwealth has additional values and objectives, such as the creation of early successional habitat for biodiversity or managing for wood production, that warrant more active forms of management.”

The committee’s report says Massachusetts is “one of the most highly forested states in the nation.” Forests cover almost 3 million acres of Massachusetts, or about 56% of the state’s land. Massachusetts forests contain more than 1.5 billion live trees.

Forest ecosystems in Massachusetts currently contain carbon stocks equal to roughly 1.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide, “or the past 15 years of statewide GHG emissions,” the report said. And Bay State forests are estimated to sequester carbon at a rate of 4.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year, with net sequestration from forestland uses equaling just more than 10% of the state’s annual emissions.

Sixty-four percent of Massachusetts forest land is owned privately, 17% is controlled by the state, 16% is held by municipalities and 3% is owned by the federal government.

The Clean Energy Transmission Working Group, created by the Legislature in its 2022 climate law, also recently wrapped up its work. In a report filed with the Senate clerk’s office Tuesday, the group laid out its view of the transmission infrastructure upgrades that may be required to support the deployment of the clean energy projects, including offshore wind, that will be key to Massachusetts’ mid-century climate goals.

Notably absent from the working group’s recommendations was anything specific around siting and permitting challenges, an issue that utility companies and others have said could determine whether Massachusetts makes good on its commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

“Existing authorities and processes applicable to siting and permitting of electric transmission in the Commonwealth pose multiple challenges to the timely development of new or upgraded transmission infrastructure,” the report said.

There is general agreement among utility companies, environmental activists and others that the energy project permitting and siting process as it exists today is a poor model. It often takes a long time to get a project through the process, it can be overly complicated for members of the public to follow proceedings, and it does not always incorporate feedback from impacted communities.

The Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy heard testimony in June on legislation related to clean energy permitting and siting, and co-chair Sen. Michael Barrett said the issue “is likely to be a major preoccupation of the Legislature.”

In September, Healey created by executive order the Commission on Clean Energy Infrastructure Siting and Permitting (CEISP). She tasked that group with giving her recommendations “concerning the reform of state and local permitting and siting processes for energy related infrastructure including, for example, options to accelerate the deployment of clean energy generation and electric distribution and transmission infrastructure while ensuring that communities have adequate input into the siting and permitting processes for said infrastructure.”

In its report, the Clean Energy Transmission Working Group “recommends that the CEISP consider the conclusions regarding siting and permitting challenges to electric transmission infrastructure addressed in this report.”

State Senate budget funds free community college for all

State Senate budget funds free community college for all ‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride

‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride Doors open at Tilton Library’s temporary home at South Deerfield Congregational Church

Doors open at Tilton Library’s temporary home at South Deerfield Congregational Church Area property deed transfers, May 2

Area property deed transfers, May 2