Guest columnist Greg White: The ravages of the overpopulation argument

| Published: 06-09-2023 10:58 AM |

Barry Roth’s “The ravages of overpopulation” [column, June 2] is deeply problematic. He offers the argument that overpopulation is the greatest threat to “habitat destruction and over-exploitation” and, indeed, more of a threat than climate change.

He adds that overpopulation is at the heart of immigration pressures, producing “waves of immigration” to the U.S. And he also seeks to inoculate himself from criticism by saying that critics of overpopulation arguments unreasonably resort to charges of racism — making the topic of human numbers a “third rail” not to be touched, as well as “the nail in the coffin that end(s) honest discussion.”

Whether someone arguing that population growth causes biodiversity loss, overexploitation, environmental destruction, and immigration is an actual racist is hard to know. We do know, however, that many purveyors of the overpopulation thesis in the past — Thomas Robert Malthus, Madison Grant, John Muir, Garrett Hardin, John Tanton, etc. — were undeniably bigoted in their arguments and work.

For his part, Malthus famously argued in 1798 that population growth will outstrip food production. As an Anglican cleric, Malthus was deeply prejudiced against Irish Catholicism and lamented the fecundity of England’s colonial subjects in Ireland. Malthus also believed that native peoples in the Western Hemisphere were savages who needed, at a minimum, to be “civilized.”

Even if we were to set aside Malthus’ bigotry, his fundamental argument seems intuitive and remains beguilingly persuasive to this day. The world’s population has grown rapidly over time — especially in the first half of the 20th century. And there is so much hunger and poverty, habitat destruction, and, of course, significant and ongoing climate change.

But correlation isn’t causation. Indeed, the biggest problem with Malthus and neo-Malthusian arguments is not only that they can be bigoted, but they are also empirically wrong.

For more than 200 years population growth has increased, yes, but food production has increased even more. To be exact, birth rates have been slowing since the 1960s. They are still high in parts of the globe, including Africa. But in Africa the rates have declined in recent decades. Yes, there is famine and poverty. But food shortages are not primarily because there are too many people. They result from a wide array of complicated historical, social and economic issues including colonial and Cold War legacies, unjust distribution systems, unequal terms of trade, corruption, flawed financial markets that distort commodity prices, environmental pressures, and profound wealth inequality.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

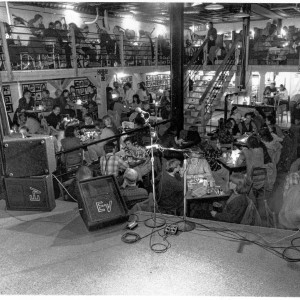

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Reyes takes helm of UMass flagship amid pro-Palestinian protests

Reyes takes helm of UMass flagship amid pro-Palestinian protests

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

In other words, there is more than enough food production in the world. What is fundamentally lacking is fair distribution. A few use far more than enough, while many have nothing.

With respect to climate change, Oxfam America released a 2022 report that demonstrated that from 1990 to 2015 the carbon emissions of the richest 1% of people globally were more than double the emissions of the poorest 50%. Put differently, the economic bottom half of the world’s population was responsible during that period for just 7% of emissions; the top 1 percent for 15%. The continent of Africa produces 4% of global carbon emissions. It seems inappropriate to blame poor people for their relatively meager environmental impact.

Contrary to Mr. Roth’s argument, overpopulation isn’t what is causing climate change or biodiversity loss or hunger. It is the economic behavior of affluent countries, firms, and individuals.

Mr. Roth also writes that the Sierra Club has banned discussions of population. In my view, the Sierra Club and other organizations in recent decades have sought to highlight the ways in which neo-Malthusian arguments have incorrectly diagnosed environmental problems and, yes, have often been framed by racist narratives.

To be clear, I would not argue that population growth is not a concern at all. I am deeply in favor of giving families — and especially girls and women — the education and resources necessary to make decisions concerning reproductive health and family planning. Reproductive justice must be at the heart of genuinely sustainable development.

But rather than dealing with the wicked complexities of distributive justice — and the fact that a small percentage of the world’s population consumes and pollutes far more than the vast majority — I fear that it is easier (perhaps) to exclaim that there are too many people. In the end, the overpopulation argument blames the wrong people.

Greg White is a professor of government at Smith College.

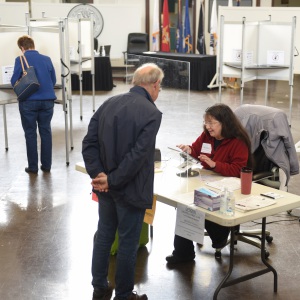

Charlene Galenski: Blake Gilmore, a strong candidate for Deerfield’s Selectboard

Charlene Galenski: Blake Gilmore, a strong candidate for Deerfield’s Selectboard Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran