The night that changed Deerfield forever: New book gives a comprehensive look at the infamous Deerfield Massacre of 1704

| Published: 02-29-2024 2:26 PM |

If you’re from the region, you’ve probably come across the story of the 1704 attack on Deerfield, or, at least one of the many monuments placed around the county commemorating the English colonists.

But how much do you really know of this time period, where the early English settlers of Deerfield dealt with harsh winters, surprise raids, and the specter of witches?

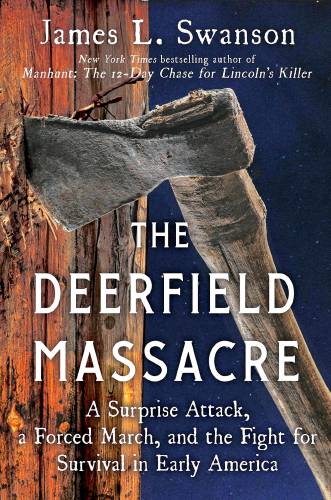

In James L. Swanson’s new book, “The Deerfield Massacre: A Surprise Attack, a Forced March, and the Fight for Survival in Early America,” which went on sale Feb. 27, the sense of paranoia and unease jumps off the pages, as the author weaves hundreds of years of history together from the Battle of Bloody Brook and the eponymous 1704 attack on Deerfield through the founding of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association in the 1800s and Historic Deerfield in the 20th century.

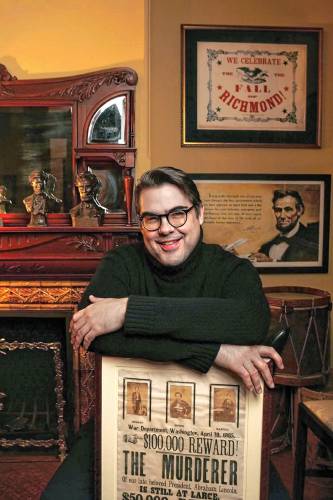

Swanson, whose previous work includes “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer” – which is being turned into an Apple+ series – said the story of Deerfield has always called to him since he attended Historic Deerfield’s summer fellowship program in 1980, calling this new book about Deerfield one of his life’s works.

“All of my books have been about moments of dramatic change in American history,” Swanson said in an interview, as he has written about both Abraham Lincoln’s and John F. Kennedy’s assassinations in the past. “People have often teased me that all of my books seem to be about death, assassination and murder … My obsession is truly about moments of dramatic change in American history, when something might change overnight in a dramatic way.”

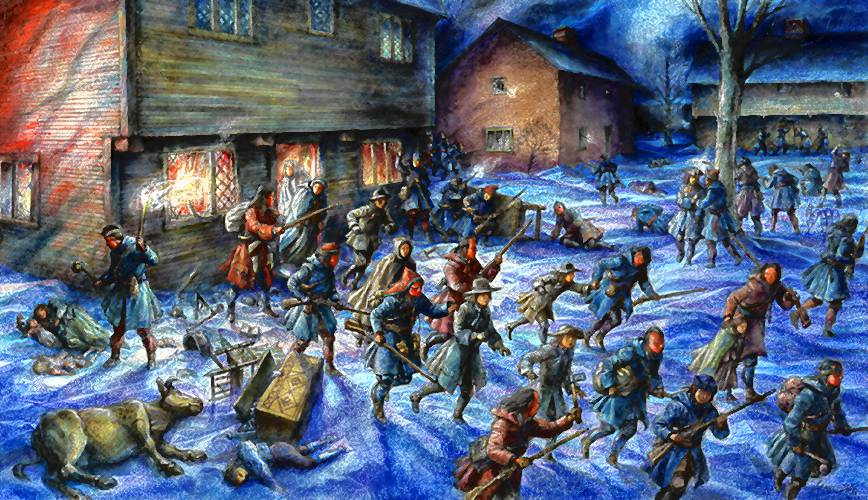

It might even be an understatement to say things dramatically changed in Deerfield in the early hours of Feb. 29, 1704. As the early settlers of Deerfield were sleeping, probably around 3 or 4 a.m., a war party of French and Native American men left their encampment, hopped over the walls of the settlement and unlocked the gate, opening the door for death and destruction.

When it was all said and done, more than 40 colonists, including children, were killed in town and more than 100 were taken captive with the intention of marching them back up to French and Native territory in Canada, where those who survived the 300-mile trek either tried to make their way back to Deerfield or they chose to remain in Quebec or join Native tribes.

“My Deerfield book really fits in with the overall theme of moments of dramatic and instant change in the American past,” Swanson said, noting the early stages of this book are a far earlier time period than his books on presidential assassinations and the Civil War. “One of the many things that captivated me about Deerfield is that this is an America we don’t recognize today … This is the vast, early America, so Deerfield is not the pretty Colonial town of the American Revolution era that it looks like today.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

A Waterfront revival: Two years after buying closed tavern, Holyoke couple set to open new event venue

‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride

‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride

3-unit, 10-bed house in backyard called too much for Amherst historic district

3-unit, 10-bed house in backyard called too much for Amherst historic district

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

UMass basketball: Matt Cross announces he’s transferring to SMU for final year of eligibility

UMass basketball: Matt Cross announces he’s transferring to SMU for final year of eligibility

Retired superintendent to lead Hampshire Regional Schools on interim basis while search for permanent boss continues

Retired superintendent to lead Hampshire Regional Schools on interim basis while search for permanent boss continues

In the era where the Salem Witch Trials were still a fresh memory and intense religious faith combined with the fear of Native attacks, Deerfield, as well as the rest of early America, was a far different place than it would be 100 or 200 years in the future.

“All the houses and structures of Deerfield are long post-massacre. The massacre happened 75 years before the American Revolution,” Swanson continued, noting the attack occurred decades before historical figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were born. “This is a time where we don’t recognize those people and they certainly wouldn’t recognize us. I really wanted to learn more and write about the early colonial time, of that vast, early America that we don’t remember or recognize anymore.”

PVMA Executive Director Tim Neumann, who worked with Swanson throughout the process, said the attack on Deerfield truly left a mark on the frontier town and that’s the most intriguing part of it.

“What I like about the story of 1704 is how it just superimposed itself on this little town and it became an icon of their experience,” Neumann said, echoing Swanson’s thoughts about connecting modern times to those settling in the Pioneer Valley. “It’s hard for a lot of 21st-century people to get into the mind of the settlers coming here.”

To tell this story, Swanson dives into numerous sources, with many being housed right here in Franklin County at PVMA and Historic Deerfield. Much of the early part of the book follows the writings and observations of Rev. John Williams, who was the town’s spiritual leader for decades and was one of the captives who survived the march up to Canada.

While survivor accounts and other literary works were retained, the only remaining relic of that cold Feb. 29 morning, is the Old Indian Door, which was a part of the Sheldon House and survived the Native and French assault that evening. The hatchet scars on the door and the hole in the middle are the only surviving reminders of the attack on Deerfield, which Swanson said came to symbolize the raid.

While the house around it was torn down in the mid-1800s — an incompetent town committee waged an unsuccessful campaign to save it — residents managed to save the door, although it had briefly moved to Chestnut Hill for a period of time before its buyer had a change of heart, which is recounted in a humorous story later in the book.

As the timeline heads into the 19th and 20th centuries, Swanson turned toward George Sheldon, the legendary Deerfield historian whose obsession with history led him to publish “A History of Deerfield, Massachusetts,” and PVMA. Those two sources, as well as Historic Deerfield, newspaper articles and other contemporary accounts allow Swanson to tell a comprehensive story of this small New England town.

“There’s less sources for the Deerfield story than, perhaps, the Kennedy assassination, but there’s lots of colonial documents,” Swanson said. “Deerfield itself, I think, is one of the best documented early American towns in history. From the beginning, people seemed obsessed with saving things, with documenting things, whether it was furniture, possessions and documents.”

The book also touches on the commercialization of the attack, which began to pick up steam about 100 years afterward, and how it came to be known as a “massacre,” despite the fact that nobody who lived through the event ever called it anything like that.

Neumann said the name of the attack is often a point of discussion and calling it a “massacre” takes the French participation out of it, while also discrediting the sophistication of the Native tribes involved in the raid.

“We’ve been among the people who have been trying to change the name to raid … the view of the attack as an Indian attack and then calling it a massacre demeans the military achievement it was,” Neumann said, emphasizing it often comes down to “settlers and the Indians,” despite the fact that it was part of a larger, drawn-out conflict between the English and French, and Native tribes had their own autonomy. “The Native groups were not duped into it, they found it served their purposes.”

It should be noted that for as thorough as Sheldon, and others, were, many historical accounts may cast a blind eye to underrepresented narratives, such as Native or Black perspectives. In the modern era, Swanson said folks like Neumann have led the charge in ensuring a more inclusive — and accurate — history is told.

“Listening is part of it,” Neumann said, emphasizing that just because something is written down, doesn’t mean it’s true. Oral traditions, he added, are such an important part of history too. “I’ve never felt that my job was to tell the truth — that doesn’t make me a liar by the way — things happened and they were interpreted by people differently.”

In Swanson’s numerous returns to Deerfield, he has observed that historical obsession still runs through residents today, especially among the many he’s had the pleasure to work with, including Neumann and Joseph Peter Spang III, the founding curator of Historic Deerfield (Swanson wrote that Spang “embodied the spirit of Old Deerfield as deeply as John Williams”).

“I think the legacy of Deerfield has been kept alive and passed on. Not just through the museums and through the artifacts and the furniture and relics, it’s somehow passed on through the communal memory of the people who live in Deerfield,” Swanson said. “Deerfield lives also in this people, not just in the stuff.”

As part of the book’s release and the 320th anniversary of the attack on Deerfield — which can actually be commemorated this year because it is a leap year — Swanson will return to town on March 3 to deliver a lecture on “The Deerfield Massacre in Memory and Myth,” which will start with the Battle of Bloody Brook and trace through the topics touched on the book.

“I like that it’s going to be at the academy,” Swanson said. “There stood the house of John Williams, there stood the Stebbins House … Essentially, the lecture is going to literally be on the site of the old palisade and on the site of the historic houses.”

The event is free and open to the public and will be held in Deerfield Academy’s Hess Auditorium, 7 Boyden Lane, at 2 p.m. Northampton’s Broadside Bookshop will be on hand to sell copies of the book and Swanson will sign books following his lecture.

PVMA’s Memorial Hall Museum will also be open from 11 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and from 3:30 to 4 p.m. on March 3, where people can get the chance to see redesigned portions of the 1704 Memorial Gallery.

“The Deerfield Massacre,” which is published by Scribner, went on sale Tuesday, Feb. 27 and can be purchased on Amazon and at regional bookshops. Additionally, the Apple+ adaptation of “Manhunt” premieres on March 15 and features Patton Oswalt, Lili Taylor, Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle.

For a taste of the deep history behind the 1704 attack on Deerfield before reading Swanson’s book, visit PVMA’s website for the attack at 1704.deerfield.history.museum.

Chris Larabee can be reached at clarabee@recorder.com.

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley

Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier

Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier