A day under the hood with Baystate Medical Center surgeon John Romanelli

| Published: 09-20-2016 8:06 AM |

Hard rock music is cranked up in the operating room and the lights are dimmed. The patient, Eileen Conway, 63, is not conscious. Only a square of her stomach is exposed. The rest of her is under a sterile, blue gauze-like fabric.

This is the start of an hour-long journey for Dr. John Romanelli at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield to find and remove her gallbladder.

As he cuts into her abdomen, Guns N’ Roses belts out “take me down to paradise city where the grass is green and the girls are pretty.” Soon a camera descends into her gut and four screens at different angles around the bed show the view as it heads into her body, on what looks like a bloody roller coaster ride.

“The big difference between dentistry and surgery is that we listen to music that keeps us awake,” says Romanelli, who also plays electric guitar in a rock cover band called Plan B.

“Music and medicine are linked. If you do a functional MRI — the same parts of the brain light up — so there are a lot of doctors who are musicians,” he says.

It’s about 8 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, the busiest surgery day of the week for Romanelli, who specializes in minimally invasive abdominal surgery at Baystate. He will be performing three operations today, a typical workload for him. On non-surgery days, he divides his time among classes and conferences, patient appointments and bedside chats. On surgery days, those tasks get sprinkled in among the operations.

During Conway’s surgery, the light is dimmed to enhance the contrast on the screen, where Romanelli’s eyes are focused.

“I do my best work in the dark,” he says.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

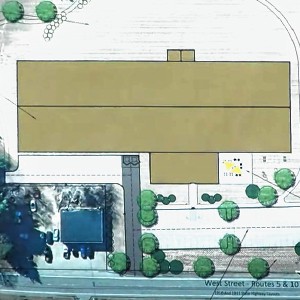

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

After the gallbladder is detached from the liver, he snags it with metal graspers and sticks it in what looks like a butterfly net, which is wrestled out of a small incision in Conway’s belly and placed into a dish. It resembles an uncooked breakfast sausage.

The gallbladder, which was filled with stones, had been causing Conway pain, says Romanelli, and had to come out. Now it’s off to pathology to be sliced and diced to make sure there is no hidden disease, he says.

The first surgery of the day is done by 8:50 a.m. and minutes later Romanelli is back in his office. Sunset photos he took in Greece and river views from the southwest of France are framed and mounted on the wall behind him.

He picks up the phone, leaning back in his chair behind his oversized L shaped desk, to call Conway’s husband, Jeff Passo.

“Hello Jeff,” he says softly. “It’s Dr. Romanelli. She did great.”

A happy tone of voice is key when calling loved ones after surgery, he says. Body language is just as important when it’s an in-person meeting.

If surgery went well, Romanelli is smiling when he walks into the family waiting room. “Even if it was a really hard case, you don’t go in there looking like you just won a war. That’s just not what they need to see,” he says.

“The memory they are going to take from that moment is the way you look. It doesn’t matter what you say after that, they know that their patient is going to be OK. They can see it in your face. You can’t fake that.”

If the news is bad, he sits with family members and looks them straight in the eyes. “I don’t beat around the bush or use unnecessary euphemisms.”

Only a few hours earlier, the sun was just starting to shine through the kitchen window at the Romanelli household in Westfield, where the doctor never drinks morning coffee.

Jittery hands are no good for a surgeon, he says.

Instead at 6:45 a.m., already smooth from head to toe wearing shiny leather shoes and a blue dress shirt under his black suit, he prepares breakfast in a blender.

A shake with two bananas, ice, low fat milk and chocolate protein powder will fuel him through the first half of his day.

He leans on the marble counter top and sips the drink out of a travel mug as his wife, Kirsten, packs three lunches for the kids, Julia, 14, Justin, 10, and Daniel, 7. The two boys are still asleep, but Julia is already getting ready for school.

Kirsten jots down an inspirational message on tiny pieces of paper and slips one in each lunch bag.

Romanelli takes a few more sips of breakfast before he kisses his wife goodbye, hops into the car and heads to Baystate.

Once there, he swaps his crisp suit for loosely fitting blue scrubs and slips on the navy blue Crocs that live under his desk.

“Every patient is like a jigsaw puzzle,” he says, as he walks through the maze of hallways and stairwells to meet his patient.

Nurses and doctors rush past him under the fluorescent lighting, wearing surgical masks and hairnets. Some are talking softly about patients, brainstorming about diagnoses or sharing angst about difficult cases.

They are pushing hospital beds and sitting at computers, logging in medical data.

Some sit near the water cooler in the surgeon’s lounge, with stethoscopes hanging around their necks, chatting about co-workers.

Four giant flat screen TV monitors hanging on the wall in a central location, show the doctors’ surgery schedules.

Romanelli gets to his second patient of the day, Nicole Cotto, 42, and pulls back the white curtain surrounding her hospital bed.

“Do you have any questions?” he asks.

“Did you get a good night’s sleep?” she responds.

“Yeah, I slept like a baby. I woke up every two hours crying, thinking about you,” he says with a smile.

Humor helps him break the ice.

Patients are usually nervous, he says, so he does what he can to make them laugh, help them relax and diffuse anxiety before the operation.

Romanelli says he tries to exude empathy and talks to them in language they will understand, avoiding medical jargon.

“They have to put their trust in me. They are asking me to cut their flesh open, use sharp tools to make a problem go away.” he said. “That trust doesn’t happen by magic, it happens by communicating on meaningful levels.”

When Romanelli walks into the operating room again, he is unflinchingly calm. Cotto is already under anesthesia.

There is a team of five people in the room, surrounding her on all sides.

“Alright, can we turn down the light to make it more romantic?” Romanelli asks.

The blood vessels in the tissues are magnified on the screen, rising and falling with every heartbeat.

The music is cranked up again, this time it’s “Come as You Are” by Nirvana. The doctor is humming along, sometimes nodding his head.

The mission this time its to remove a gastric lap band and Cotto’s gallbladder.

As Romanelli guides the camera mounted on a long, thin instrument though Cotto’s abdomen, yellow and pink tissues appear on the screen, forming seemingly never-ending nooks and crannies like rock formations or caves in the American Southwest.

Romanelli guides the movement of the other long, pencil-like tools inside the woman’s body— which are poking out from a few small incisions in her torso — with his hands.

The tools have tiny graspers on one end and a scissor-like handle on the other.

His only view of the area he is working on is on a screen just above him.

“Your mind’s eye has to convert that to 3D, so over years of training you learn depth,” he says. “You have to learn three dimensional space represented two dimensionally.”

A tiny hook-like instrument burns through the tissue and coagulates the blood as he digs out the lap band, which has embedded in the liver. He pulls out a port and tube which was connected to the lap band.

As the tissue burns, smoke clouds the screen, and a pungent smell fills the air.

This doesn’t faze the doctor. “It is up in your face, the smell of charred flesh,” he says, “It took me a year to get used to it.”

Lunch at the hospital cafeteria comes fast after surgery. He drizzles Italian dressing on the romaine leaves of his antipasto salad and munches through it quickly.

Salad is his usual choice if he has the time to stand in the salad line, he says.

“I try to eat as healthy as I can. I do believe that you should practice what you preach. I spend a lot of time telling obese patients to make better food choices.”

He washes it down with cranberry lime seltzer, while chatting about the national election coverage playing on the TV above.

He is a Republican, he says, but doesn’t really like either candidate. He’s leaning toward voting for Donald Trump.

By 3 p.m. a third belly is waiting on the operating room table.

It belongs to Robert Cichocki, 74, who is getting a hernia repaired. His abdomen is puffed out, inflated with carbon dioxide, which helps the doctor see and maneuver through Cichocki’s body.

As in the first two surgeries, the camera takes a plunge into an incision, and then moves through the tissue, revealing an alien landscape.

Somewhere in there, Romanelli finds the hernia, a bulge where fat has pushed through the abdominal wall. He patches it with a piece of mesh.

“We roll it up like a window shade,” he says.

When he has finished Cichocki’s operation, he has been working for a total of seven hours.

Smiling as promised, he breezes into the family waiting room to greet the patient’s wife, Florence.

“It was great, no problem,” he says, placing his hand on her shoulder.

“No driving for a week. (Have him) take the pain medication. He doesn’t get gold stars for suffering.”

Romanelli says he initially went into medicine to become a neurologist at the Medical College of Pennsylvania after watching his mother suffer from multiple sclerosis. But he fell in love with surgery during his student rotations at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh. Neurology came easy to him, he says, and he was disappointed when he didn’t find the material challenging enough. He remembers thinking that he was peaking in his chosen field at age 22.

He remembers thinking, “If I’m good at this now, then what? It freaked me out.”

He also was frustrated with neurology when he had to diagnose and deliver bad news, often without any way to fix the problems.

He wanted to offer solutions, he says, not just identify issues.

Other areas of medicine also left him disappointed. “I did pediatrics. I hated it in 30 seconds. I did psychiatrics. I almost became a patient,” he says.

“When I did surgery, the light bulb turned on for me,” he says. “I thought, ‘Wow, we are really helping these people.”

Romanelli specializes in all types of abdominal surgery and is the medical director of the Weight Loss Surgery Program at Baystate. “I like the anatomy and pathophysiology of digestive disease, which is why I went that route,” he says. “...you have to be fascinated by the disease processes you treat, or you will end up unhappy and unfilled.”

Now, after years of practicing as a surgeon he says he is still learning at age 46. “I think I’ll peak when I am 55.”

Cichocki is his last surgical patient of the day. After finishing up some more business and participating in a long conference call, Romanelli pulls into his driveway shortly before 8 p.m. The sun has already gone down and his family is there to greet him.

His children have eaten dinner and will be heading to bed soon. There is laughter and conversation as Romanelli asks each of them about his or her day. One bit of excitement: Justin, the 10-year-old, got a new flute and Romanelli takes a turn blowing it.

Once the children have gone off to bed, he sits down with Kirsten to eat the dinner she has prepared — Greek salad with chicken.

It’s been a long, busy day, but, Romanelli is content as he reflects: “...All things considered, that was an easy day for me.”

Lisa Spear can be reached at lspear@gazettenet.com.

Valley Bounty: Grass-fed animals that feed the grass: Gwydyr Farm in Southampton focuses on ‘restoring the connection between land, food and people’

Valley Bounty: Grass-fed animals that feed the grass: Gwydyr Farm in Southampton focuses on ‘restoring the connection between land, food and people’ Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton  Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night

Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances

Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances