Columnist Olin Rose-Bardawil: Demonization won’t help heal divisions

Olin Rose-Bardawil STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

|

Published: 03-18-2024 4:50 PM

Modified: 03-18-2024 8:06 PM |

By OLIN ROSE-BARDAWIL

In recent years, there has been a substantial shift in the way politicians talk about the polarization in our nation.

Just a few years ago, leading up to the 2020 election and before that, politicians, pundits, and everyday Americans frequently lamented the divisions that have caused so much anger in this country. These issues were so frequently discussed, I believe, because we had a collective understanding that we had to quickly course-correct to heal the social wounds opened during the Trump administration.

Unlike today, the state of division between Republicans and Democrats — and more deeply between two dueling visions for America — was treated as a temporary condition; not a permanent fate. We thought division was something we would get through, just as we had done during many other times throughout our enduring history.

It was in this context that many of the Democratic candidates who ran for president in 2020 made unifying the country a major part of their platform. This was notable for Joe Biden, who entered the race as a moderate hoping to restore the “soul of America.” Biden carried this message explicitly all the way up to the start of his presidency, when he often reaffirmed his pledge to govern beyond party politics: “I will work to be a president who seeks not to divide but unify. I won’t see red states and blue states, I will always see the United States,” Biden stated during his inaugural address.

However, as he began his presidency this message seemed to fade. It was as if once he was actually confronted with the issues at hand his plan to unify Americans on issues of policy and principle was no longer tenable.

Now we are more than halfway through Biden’s first term, with the next election fast approaching. Talking about unity as a goal for the near future is beginning to seem not only untenable but almost stupidly cliche. Candidates on both sides called 2020 the “most consequential election of our lives” but are using this very same language for what is before us in 2024.

Politicians, at least from what I have observed, have stopped talking about unification altogether. Biden himself does not seem to be prioritizing national unity going into the election, rather, he seems focused on stopping the “MAGA Republican extremists.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

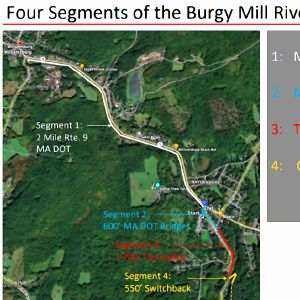

Haydenville residents resist Greenway trail plan, float alternative design

Haydenville residents resist Greenway trail plan, float alternative design

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

I agree that stopping Donald Trump is a driving issue in this election. However, the fact that we seem to have stopped talking about the very divisions his candidacy represents and the means by which we can address them raises some very concerning questions.

Are we too far gone? Has irreparable damage been done? If we are judging by the rhetoric around “unity” by politicians and journalists alike, then the answer probably would be yes.

Yet I do not believe that it has to be. Many on the left will blame our divisions on right-wing extremists, claiming that it is impossible to talk to Trump supporters because they deny election results or hold fascist beliefs. And it is this mindset, actually, that reinforces the environment of division.

While condemning some Trump supporters’ extreme beliefs is one thing, dismissing the needs and concerns that drive their beliefs is another. If anything, ostracizing political adversaries fosters more extremism than it prevents.

The journalist Jeff Sharlet puts this phenomenon on full display in his book “The Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War,” which documents the movement of far-right, Trump-inspired extremism unfolding across the nation that Sharlet believes poses a real threat to our democracy. His reporting illuminates that this movement is not taking place unprovoked — there are millions of working-class, rural Americans who currently feel desperately disenfranchised by the American establishment and pushed to poles of extremism by a society they believe no longer cares for them.

I think more and more Americans are implicitly waking up to the futility of making politics about the demonization of the other side. This is why we have been hearing more about issues like the economy and the border, which an increasing number of Americans from both sides of the political spectrum have real concerns about.

Simply attacking Trump’s disregard for the law has proved to be not enough to sway voters in Biden’s favor, and there seems to be an emerging faction of American voters who are getting tired of the partisanship that has dominated the discourse.

I have observed that people in my age group, including those who may soon be voting for the first time, are tired of the current climate and just feel disengaged.

This theme transcends political divisions: Americans can agree that this political reality is not working. Democrats need to develop and sell a vision for the future that is about more than just keeping Trump’s extremism at bay. And Republicans, conversely, will have to return to true conservative policy proposals in place of their current recklessness if they want to remain a party.

In the Valley, where liberals don’t often hear viewpoints that differ much from their own, it can become easy to demonize the other side almost without second thought.

We don’t have to live in an atmosphere where the main political goal is to dismiss those with whom we disagree as “extremists.” We can instead make efforts to engage with curiosity about the needs and struggles that motivate peoples’ positions. Because a country that does not talk is not a country for very long. And, as Sharlet points out, the longer we refuse to engage, the closer to civil war we will come. We can do better.

Olin Rose-Bardawil of Florence is a new columnist whose writings from a youth perspective will appear monthly in the Gazette. He is a student at the Williston Northampton School and the editor in chief of the school’s newspaper, The Willistonian.

Charlene Galenski: Blake Gilmore, a strong candidate for Deerfield’s Selectboard

Charlene Galenski: Blake Gilmore, a strong candidate for Deerfield’s Selectboard Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran