Slow-moving disaster looms: UMass experts contribute to cryosphere report on display at COP28

| Published: 12-11-2023 7:03 PM |

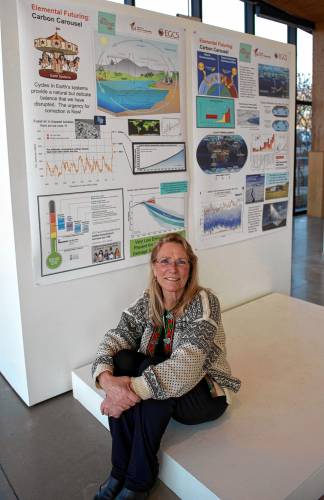

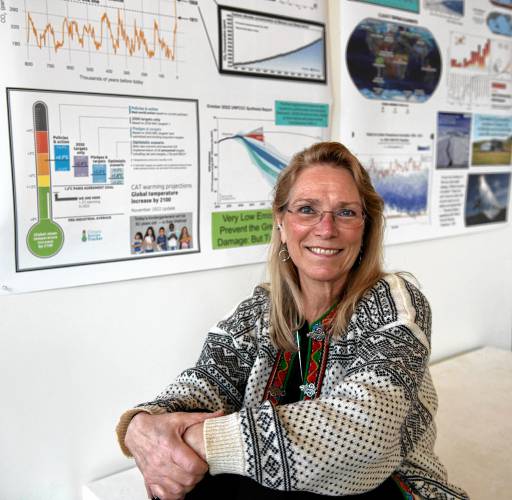

AMHERST — Ice once both founded and hindered research for glacial geologist Julie Brigham-Grette.

As a graduate student working off the coast of Alaska four decades ago, loose sea ice would accumulate onto the shores of Brigham-Grette’s campsite and barricade her 16-foot inflatable boat with a large ice puzzle. Hindered from gathering data, she’d wait out the wind, hoping a change in direction would create a path to sea.

Around 20 years later, Brigham-Grette learned from her mistake in graduate school and rode on an icebreaker ship in the Chukchi Sea, a body of water just above the Bering Strait, expecting to run into sea ice.

Only she never saw ice. It had shrunk and retreated 200 meters north.

“In the 40 years of my career, I’ve seen huge changes in the extent of ice in summer and it is no longer a barrier,” Brigham-Grette said.

Brigham-Grette, who directs the University of Massachusetts Geosciences Graduate Program, specializes in glaciers and sea level rise, topics inversely interconnected since shrinking glaciers contribute to sea level rise. She studies ancient Arctic environments by extracting parts of Earth’s crust or ice sheet and analyzing the layers to glimpse into past warming periods caused by Earth’s orbit. Through her research, Brigham-Grette can predict the effects of a warmer global temperature based on the Earth’s past reactions.

“So we know when it gets warmer, either because of orbital changes or CO2, the response is going to be similar, right, warming is warming,” Brigham-Grette said. “So I know of places in Alaska where because of those orbital changes, places today that were just tundra had trees.”

Even at its warmest, Earth’s atmosphere has never held this much CO2. Her research, along with hundreds of other studies by scientists studying the frozen areas of Earth, demonstrates the disastrous impact of climate change on the cryosphere, a term for all the frozen areas of Earth.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

Proposed Hatfield pickleball/tennis building raising eyebrows

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

South Hadley man killed in I-91 crash

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Some of that research is on display at the United Nation’s climate conference in Dubai this week, in the form of the State of the Cryosphere 2023 report, a document detailing the impacts of rising global temperatures on sea ice, ice sheets, glaciers, permafrost and ocean acidification.

Brigham-Grette and UMass colleague Rob DeConto contributed to and helped edit the report from the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, which seeks to demonstrate to delegates at the Conference of the Parties, or COP28, the catastrophic effect on the planet’s frozen areas for every 10th of a degree the Earth warms past pre-industrial temperatures.

The report concludes that the cryosphere will shrink dramatically under the 2°C target put forward by the 2015 Paris agreement. In fact, even a 1°C or 1.5°C is past the tipping point for certain areas. Arctic sea ice, according to the report, will completely disappear during summer months for at least a few weeks at 1.5°C. Greenland and parts of Antarctica face detrimental melting at the same temperature. The West Antarctic ice sheet, for instance, has a threshold of 0.8°C, a tipping point humanity has already passed.

“Over time, we’ve realized that the actual Earth is so sensitive to even a 1 or 2 degree temperature change that we’ve had to ratchet back what we can tolerate in terms of an increase in the planet,” the UMass scientist said.

But since temperatures have already climbed to 1.2°C past pre-industrial levels, Brigham-Grette agreed with the cryosphere report: A limit of 1.6°C is the only option.

The loss of snow and ice on Earth snowballs quickly and irreversibly. The cryosphere regulates solar radiation from the sun due to the highly reflective surfaces of snow and ice. As less snow falls and ice shrinks, more dark open ocean and bare mountains absorb the heat from sunlight and carbon dioxide from fossil fuel emissions, increasing the temperature and acidity of the ocean.

Warmer waters mean faster melting and less ice reformation, expanding the surface area that’s absorbing more heat. This negative reaction creates what scientists call a positive feedback loop, an effect Brigham-Grette said will occur during the Arctic’s ice-free summers.

“But we’re facing an ice-free Arctic inevitably,” she said. “Once you lose the reflectivity, you turn the white ice-covered Arctic into a dark, open ocean, you’re then absorbing that much more heat, which makes it even more difficult.”

Brigham-Grette’s research has not only allowed her to witness climate change’s impacts on nature firsthand, but its impact on people. According to the studies in the State of the Cryosphere Report, the continued melting of ice sheets and sea ice result in sea-level rise anywhere between 12 and 20 meters when global temperatures hit 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

Brigham-Grette works with indigenous villages on the coast of Alaska who may be pushed out of their ancestral lands by higher sea levels.

“We tend to hear people at COP talk about Bangladesh, but if you look at Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, Florida, there are anywhere from 6 to 10 million people estimated to need to move in the next couple decades,” she said. “And where are they gonna move? Who’s gonna build the schools for them? Where are they all going to get jobs? It’s a slow-moving disaster.”

The State of the Cryosphere Report explains that as the Arctic Ocean warms, it thaws coastal permafrost. A frozen layer of rock, gravel, stone and ice, permafrost harbors carbon from millions of years worth of dead biomass, too frozen to decompose and release carbon dioxide. As the soil defrosts from higher global temperatures and warmer coastal waters, the dead matter breaks down and releases carbon dioxide and methane.

At 2°C, the permafrost will emit enough greenhouse gases to match the entire European Union’s emissions from 2019 every year for the next one to two centuries. If humanity continues to burn fossil fuels at the current rate, 70% of the permafrost will thaw by 2100.

These findings are only the report’s tip of the iceberg. At 2°C, tropical and mountain glaciers important for agricultural and drinking water will melt in High Mountain Asia and Peru, deeming some areas inhabitable. When these glaciers melt and turn into lakes, an estimated 15 million people will become vulnerable to glacier lake outburst floods.

Snow cover will both decrease and oscillate between little snowfall and snow-heavy winters. Snow will melt faster and earlier, preventing snowpack and harming agricultural and power systems dependent on snow runoff.

While damage to the cryosphere from current carbon emission levels is unavoidable, curbing fossil fuel use will save most of this climate system, The State of the Cryosphere states. It outlines a “very low emissions” pathway to peak global temperature rise at 1.6°C and then begin a steady decline of temperature at 2100. This plan reduces greenhouse gas to 43% of the 2019 levels by 2030, reaches carbon neutrality by 2050, and begins carbon drawdown and carbon capture afterward. Brigham-Grette said to regrow glaciers, the carbon levels in the atmosphere would need to return to below 300 parts per million.

It starts with an acute cut of fossil fuel usage — an action, according to Reuters, currently on the negotiating table at COP28 for the first time in 30 years of international climate talks.

UMass Environmental Conservation Professor Anita Milman said countries don’t disagree that climate change is an issue, but rather on actions required, the severity of those actions, and who takes responsibility for that action. At the U.N. Climate Conference, for instance, countries are divided on whether to phase out fossil fuels or simply reduce pollution, two completely different actions.

“We need to reach an agreement on what pathways, whose going to decide on those pathways and how to make those pathways happen. And governments don’t have enough power to do that necessarily,” Millman said.

Yet Brigham-Grette remains hopeful.

“Everything’s possible, it’s whether we’ll do it. I think we have to only try. We may not make it but we have to try. We have to be able to look back and have that ‘no regrets,’” she said.

Emilee Klein can be reached at eklein@gazettenet.com.

State Senate budget funds free community college for all

State Senate budget funds free community college for all ‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride

‘We can just be who we are’: Thousands show support for LGBTQ community at Hampshire Pride Doors open at Tilton Library’s temporary home at South Deerfield Congregational Church

Doors open at Tilton Library’s temporary home at South Deerfield Congregational Church Area property deed transfers, May 2

Area property deed transfers, May 2