Chalk Talk: Park ranger brings beard and much more to classroom

| Published: 12-14-2023 11:21 AM |

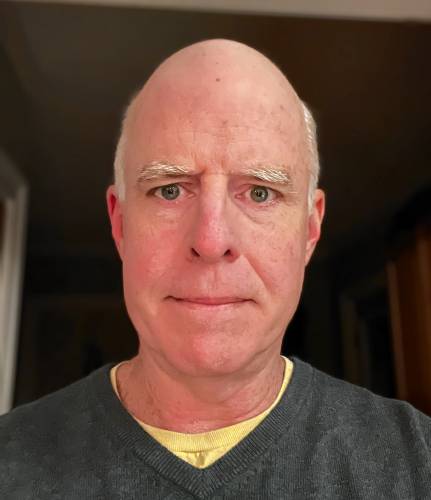

The moment he steps into the classroom, his beard attracts attention. It couldn’t be otherwise, really, given the length, depth and visibility of it.

Even the shyest students are intrigued, as they pepper him with questions such as how long it has taken to grow the beard, whether he ever wears a ribbon in it, if it’s hot in the summer, and so on.

These moments always make me chuckle, but I also know that the beard of National Park Ranger Scott Gausen is just one of the many intentional ways he lowers the barrier between his work as an interpretative park ranger and the young people he is trying to reach.

The near-instant connection he establishes in these interactions quickly leads to valuable learning time when Ranger Scott, as he likes to be known, launches into a topic he is deeply versed in and passionate about in his job at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site: the mission of the National Park Service to preserve and celebrate natural and cultural resources of the United States.

I’ve been fortunate, along with fellow Western Massachusetts Writing Project colleague Harriet Kulig, to work with Ranger Scott on any number of projects for the past seven years. The three of us, along with other partners, have run graduate-level courses with local history themes; facilitated youth summer writing camps at the Springfield Armory and inside Springfield public schools; hosted workshops at various WMWP events for other teachers; presented our work to a wider audience at National Writing Project events; and more.

But it’s watching Ranger Scott’s impact on my own sixth grade students that gives me the most satisfaction. Each year, during the annual Write Out event — which takes place in October, lasting for two weeks, as a partnership between the National Writing Project and the National Park Service — Ranger Scott comes to my classroom in Southampton to share information about the 400-plus National Park Service sites and to spark interest in place-based learning.

This year, Ranger Scott spent the day of Oct. 20 — the National Day on Writing — with my sixth grade writers, engaging them in deep inquiry about the history of the National Park Service, the symbolic elements of the park service emblem and badge, and the value of not just the large park sites like Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, but the smaller sites nestled inside urban centers and designated areas including national seashores (such as Cape Cod), national lakeshores (such as along Lake Michigan), trails (including the Appalachian Trail), and recreation areas.

My students were in the midst of their own research projects about a national park site when Ranger Scott visited, and his wealth of insights and information about parks helped deepen their understanding of the places they were learning more about through online work, and would soon be presenting to the classes.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

For all my work as a resource to my students, there’s real magic in having a park ranger right in front of them, answering questions and regaling them with stories of parks where he has worked (Oregon Caves National Park was his first job) and visited (Crater Lake National Park is his favorite).

Most years, when Ranger Scott visits, we head outside for part of the class — writing outside is a key component of the Write Out initiative, which features video writing prompts from national park rangers from sites across the country, with invitations into writing activities — in order for my students to do a tree mapping activity, in which they mark out every single tree growing on our school property.

This gives them a new appreciation for the trees they see every day but rarely notice, and also a sense of where shade trees have been planted and why. Alas, Mother Nature’s rainy nature arrived this year, keeping us indoors, which allowed Ranger Scott more time to interact with my students.

Other writing activities we engaged in with Write Out this year included gathering sensory imagery and turning those into haiku poems; using a single found leaf as inspiration for story writing and for creating a map, with the stem and veins of the leaf becoming roads and rivers for an imaginary place; composing six-word stories of a place; and writing dialogue between trees, after watching another ranger video from Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park in California.

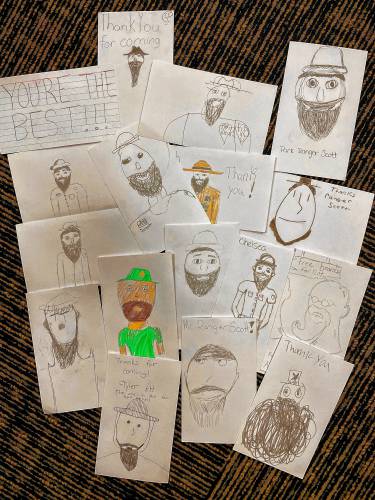

Yet, it’s always the beard they will remember most fondly, and after Ranger Scott has gone on his way, my students get down to work on one final bit of Write Out writing: a thank-you note to the ranger, complete with individual sketch drawings of his legendary beard.

The things they draw would make you laugh, and that joy of connection is a critical point of bringing expert visitors to the classroom, after all.

Kevin Hodgson is a sixth grade teacher at William E. Norris Elementary School in Southampton and a teacher-consultant with the Western Massachusetts Writing Project.

Valley Bounty: Grass-fed animals that feed the grass: Gwydyr Farm in Southampton focuses on ‘restoring the connection between land, food and people’

Valley Bounty: Grass-fed animals that feed the grass: Gwydyr Farm in Southampton focuses on ‘restoring the connection between land, food and people’ Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton  Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night

Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances

Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances