Latest News

Hadley eyes smart growth zoning district

Hadley eyes smart growth zoning district

Extreme weather forces valley farmers to adapt

Extreme weather forces valley farmers to adapt

A Look Back, May 11

A Look Back, May 11

Northampton school budget: Tensions high awaiting mayor’s move

NORTHAMPTON — As the deadline for Mayor Gina-Louise Sciarra to a submit a budget proposal for the city draws near, an entrenched battle over the city’s public school budget is coming to a head.The Northampton School Committee defied the mayor’s...

A rocky ride on Easthampton’s Union Street: Businesses struggling with overhaul look forward to end result

EASTHAMPTON — Outside of Small Oven bakery on Union Street, customers walk carefully around puddles, leaving footprints in the muddy strip where the sidewalk had been just days before. Inside, a line still forms at the register, but according to owner...

Most Read

Northampton school budget: Tensions high awaiting mayor’s move

Northampton school budget: Tensions high awaiting mayor’s move

A rocky ride on Easthampton’s Union Street: Businesses struggling with overhaul look forward to end result

A rocky ride on Easthampton’s Union Street: Businesses struggling with overhaul look forward to end result

‘None of us deserved this’: Community members arrested at UMass Gaza protest critical of crackdown

‘None of us deserved this’: Community members arrested at UMass Gaza protest critical of crackdown

Guest columnist David Narkewicz: Fiscal Stability Plan beats school budget overreach

Guest columnist David Narkewicz: Fiscal Stability Plan beats school budget overreach

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field

Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field

Editors Picks

A Look Back, May 10

A Look Back, May 10

A lot of imagination: Hopkins seniors bring art to parking lot spots

A lot of imagination: Hopkins seniors bring art to parking lot spots

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia

Arts Briefs: Dance festival and a one-woman play in Northampton, summer music fests in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: Dance festival and a one-woman play in Northampton, summer music fests in Easthampton, and more

Sports

Boys lacrosse: Amherst’s Skyler Ferro records 200th career point in win over Pope Francis

Amherst boys lacrosse attack Skyler Ferro tallied his 200th career point on Friday night in a 9-4 win over Pope Francis.He needed just two points to reach the milestone, and finished with five – two goals and three assists. On his 200th career point,...

Opinion

Rebecca Lee: Counter corporate capture

In Olin Rose-Bardawil’s column “Corporate capture a grave threat to citizens” [Gazette, April 11], he argues that corporate involvement in agencies is determining federal regulations, which results in increased profits for industries, leaving people...

Jim Reis: Northampton school budget — What went wrong?

Jim Reis: Northampton school budget — What went wrong?

Columnist Olin Rose-Bardawil: American dream out of reach for many

Columnist Olin Rose-Bardawil: American dream out of reach for many

Martha Jorz: Stop supporting UMass and Raytheon

Martha Jorz: Stop supporting UMass and Raytheon

Tony Giardina: Faith and inclusion

Tony Giardina: Faith and inclusion

Business

Area property deed transfers, May 2

AMHERST Faheem Ibrahim Lt and Faheem Ibrahim to Nan Zhao and Zhihong Ni, 16 Arbor Way, $738,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 1, $218,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 2,...

Arts & Life

Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets

Local wool for your wardrobe … and for your garden?That’s the idea behind a new project from Western Massachusetts Fibershed, an organization working to strengthen our local fiber economy, right alongside our local food economy.Peggy Hart is a core...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Jean S. Miller

Jean S. Miller

Jean S Miller Southampton, MA - Jean Spink Miller, of Southampton, Massachusetts, passed away in her home on April 30, 2024. She was a graduate of Amherst High School (Class of 1970), after which Jean became an editor and technical write... remainder of obit for Jean S. Miller

Carol F. Keller

Carol F. Keller

Northampton, MA - Carol F. (Hirst) Keller passed away peacefully at home on May 7, 2024, surrounded by her loving family. Carol was born October 31, 1934, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the daughter of the late Carleton and Helen (Carro... remainder of obit for Carol F. Keller

Mark Woods Dowling

Mark Woods Dowling

Easthampton, MA - Mark Woods Dowling, 71, of Easthampton, Massachusetts, was called to his eternal home in heaven by his Savior and Lord Jesus Christ on April 25, 2024 following years of bravely battling cancer and the long-term effects... remainder of obit for Mark Woods Dowling

Northampton man held without bail in December shooting

Northampton man held without bail in December shooting

Hatfield Town Meeting to consider $1.4M for plant upgrades as part of 28-article warrant on Tuesday

Hatfield Town Meeting to consider $1.4M for plant upgrades as part of 28-article warrant on Tuesday

Area briefs: Hadley candidates forum slated for Monday

Area briefs: Hadley candidates forum slated for Monday

Columnist Bill Newman: Laurels and the laureate

Columnist Bill Newman: Laurels and the laureate

Big turnout expected Sunday for 14th annual WMass Mother’s Day Half Marathon in Whately

Big turnout expected Sunday for 14th annual WMass Mother’s Day Half Marathon in Whately Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field

Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field Mother's Day extra special for Northampton girls soccer coach Vanessa Butynski

Mother's Day extra special for Northampton girls soccer coach Vanessa Butynski South Hadley baseball gets past Hampshire Regional in Hartford: ‘it’s almost like the big leagues’ (PHOTOS)

South Hadley baseball gets past Hampshire Regional in Hartford: ‘it’s almost like the big leagues’ (PHOTOS) Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

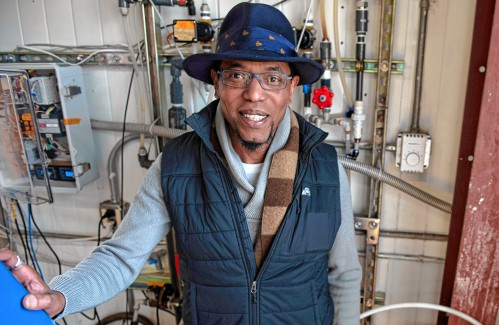

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city  Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season

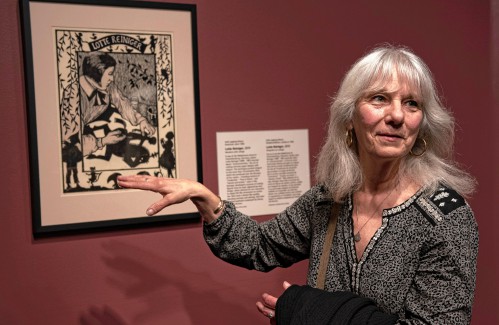

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past

Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body