Latest News

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

AMHERST — A day after 132 people were arrested in pro-Palestinian protests on the University of Massachusetts campus, the university’s student government Wednesday night formally declared it had no confidence in Chancellor Javier Reyes and his...

‘Knitting treasure’ of the Valley: Northampton Wools owner spreads passion for ancient pastime

NORTHAMPTON — Above the rows of shelves at Northampton Wools, amid all of the yarn of different colors, materials and thickness that fill every cubby in sight, sits a famous sweater worn by Charlize Theron in the Academy Award-winning film “The Cider...

Most Read

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Public gets a look at progress on Northampton Resilience Hub

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

Northampton bans auto dealerships near downtown; zone change won’t affect Volvo operation on King Street

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Town manager’s plan shorts Amherst Regional Schools’ budget

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Police respond to alcohol-fueled incidents in Amherst

Editors Picks

A Look Back, May 9

A Look Back, May 9

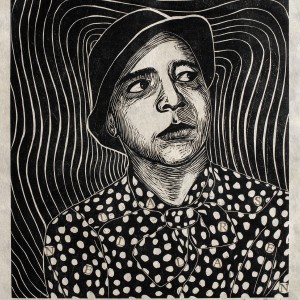

Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past

Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past

Karen Gardner: We all deserve a break

Karen Gardner: We all deserve a break

Arts Briefs: Dance festival and a one-woman play in Northampton, summer music fests in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: Dance festival and a one-woman play in Northampton, summer music fests in Easthampton, and more

Sports

Boys volleyball: Granby cruises to 3-0 sweep over Athol (PHOTOS)

GRANBY – Michael Swanigan and Braeden Gallagher had just taken the volleyball net down from another win Wednesday night, but they weren’t ready to pack up the balls just yet.The two went off to the side of the gym and began hitting at each other,...

Opinion

Martha Jorz: Stop supporting UMass and Raytheon

To those protesting the war and genocide in Gaza, refusing to support those institutions with monetary gifts is also an option. If we stop financially supporting and investing in those institutions that make the production of weapons of war possible...

Tony Giardina: Faith and inclusion

Tony Giardina: Faith and inclusion

John Frey: School Committee must practice prudent fiscal management

John Frey: School Committee must practice prudent fiscal management

Doron Goldman: Israel's situation is complicated

Doron Goldman: Israel's situation is complicated

Jeanne Horrigan: Amherst seniors grateful for ARPA support

Jeanne Horrigan: Amherst seniors grateful for ARPA support

Business

Area property deed transfers, May 2

AMHERST Faheem Ibrahim Lt and Faheem Ibrahim to Nan Zhao and Zhihong Ni, 16 Arbor Way, $738,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 1, $218,000 Richard B. Spurgin to Yg Pleasant LLC, East Pleasant Street, Lot 2,...

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

We’ve reached that point in the school year when it is actually painful (I mean physically painful) for me to leave my yard in the morning. May is the true month of the reawakening and blooming of Nature’s splendor and last week she was in full...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Lori E. Christenson

Lori E. Christenson

Winston-Salem, NC - To my family and friends: With great sadness, I wish to announce the passing of Lori Christenson, my beloved wife of 40 years, who died peacefully at our home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina on February 20th, 2024. ... remainder of obit for Lori E. Christenson

Helen Czelusniak

Helen Czelusniak

South Kingstown, RI - Helen A. (Fil) Czelusniak formerly of Easthampton, died on March 22, 2024 at South County Hospital in South Kingstown, RI. Born in Hadley, she was 97 years old. Helen graduated from Hopkins Academy and Northampton... remainder of obit for Helen Czelusniak

Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Wilford J. Morton, Jr. Belchertown, MA - Wilford J. Morton, Jr., beloved husband, father, and friend, passed away peacefully on April 14, 2024, at the age of 85. Wilford was born on September 17, 1938, in Waltham, Massachusetts, to his p... remainder of obit for Wilford J. Morton Jr.

Columnist Olin Rose-Bardawil: American dream out of reach for many

Columnist Olin Rose-Bardawil: American dream out of reach for many

VA preps for birthday bash: Leeds medical center to mark 100 with circus acts, games and visits by prominent leaders

VA preps for birthday bash: Leeds medical center to mark 100 with circus acts, games and visits by prominent leaders

Chesterfield budget, up 4.5%, faces Town Meeting vote Monday

Chesterfield budget, up 4.5%, faces Town Meeting vote Monday

No contested seats in Southampton election May 21

No contested seats in Southampton election May 21

Health board seat sole contested race in Pelham election Tuesday

Health board seat sole contested race in Pelham election Tuesday

Area briefs: Walk for peace in Gaza; high blood pressure support group forms; Velis honor work recovery work

Area briefs: Walk for peace in Gaza; high blood pressure support group forms; Velis honor work recovery work

Guest columnist Josh Silver: Northampton school budget — Let’s start with kindness, accuracy and respect

Guest columnist Josh Silver: Northampton school budget — Let’s start with kindness, accuracy and respect

With Jones project in question, Amherst won’t sign lease for temporary digs

With Jones project in question, Amherst won’t sign lease for temporary digs

Amherst College faculty join students in urging divestment from military suppliers to Israel

Amherst College faculty join students in urging divestment from military suppliers to Israel

Baseball: Hampshire, South Hadley to ‘get a little taste of what it’s like to be a pro’ at Dunkin’ Park

Baseball: Hampshire, South Hadley to ‘get a little taste of what it’s like to be a pro’ at Dunkin’ Park Belchertown Twirlers capture first place at Northeast Regional Championships

Belchertown Twirlers capture first place at Northeast Regional Championships UMass basketball: Minutemen nab another transfer in Arizona State forward Akil Watson

UMass basketball: Minutemen nab another transfer in Arizona State forward Akil Watson UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason

UMass basketball: Bryant forward Daniel Rivera to be Minutemen’s first transfer of the offseason Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

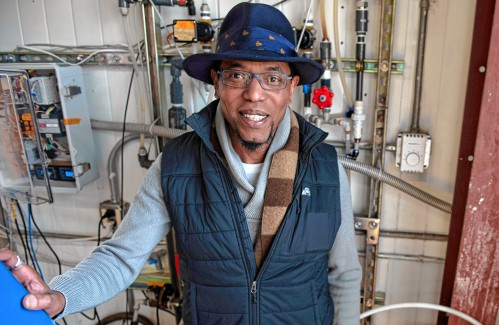

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city  Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body

Easthampton author Emily Nagoski has done the research: It’s OK to love your body Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley

Earth Matters: Honoring a local hero: After 40 years, Hitchcock Center bids farewell to educator and creative leader, Colleen Kelley Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier

Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier