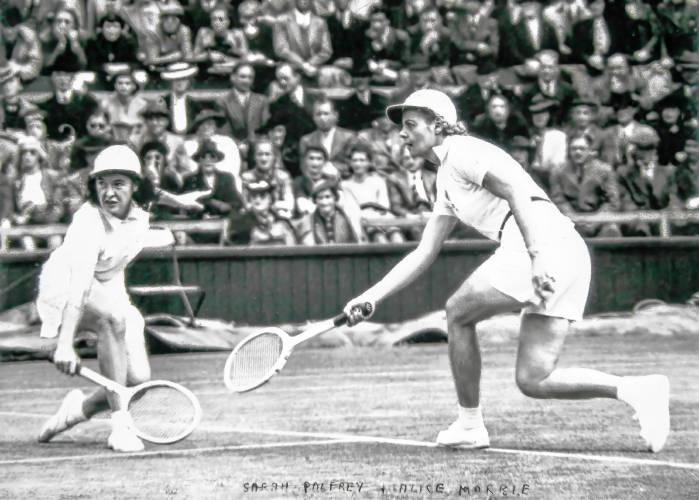

‘Queen of the Court’: Madeleine Blais’ new book takes a fresh look at tennis star Alice Marble of the 1930s

| Published: 10-23-2023 10:27 AM |

Tennis star. Tennis innovator. A celebrity in her day who appeared on the cover of LIFE magazine. A woman who also sang professionally, designed clothes, worked as a sports columnist, hobnobbed with movie stars, and rebuilt her tennis career after a crippling illness threatened to end it.

But Madeleine Blais, in her newest book, contends that Alice Marble is largely forgotten today, even though she pushed for more equal pay and treatment of female athletes and helped break the color barrier in tennis in the early 1950s.

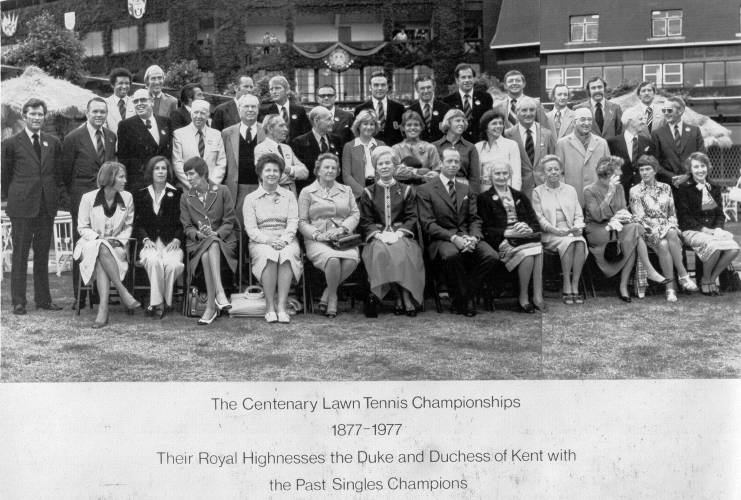

“Queen of the Court: The Many Lives of Alice Marble” aims to bring the former Wimbledon and U.S. Open winner back to the limelight. This deeply researched biography offers an illuminating look at a major star of her era — but it also portrays a woman whose later life was marked increasingly by loneliness, economic hardship, and perhaps some self-delusion.

Blais, the Pulitzer Prize winning writer and professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, says an editor suggested several years ago that Marble, the women’s Wimbledon and U.S. Open champion of 1939, could be a good topic for a book.

In a recent phone interview, Blais said she was somewhat familiar with Marble’s name; her late mother, who was born the same year (1913) as Marble, sometimes talked about her. But that was about the extent of her knowledge, Blais noted.

Once she began looking into Marble’s story, though, “I was hooked,” she said. “The more I learned, the more interesting it became.”

Marble’s life, Blais notes, “is really the story of the 20th century.”

For starters, she came from a working class background to excel at a sport that “mostly catered to the elite,” as Blais puts it, and she became a household name during the dark days of the Great Depression, when people turned to sports for distraction and some positive news.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Northampton school budget: Tensions high awaiting mayor’s move

Northampton school budget: Tensions high awaiting mayor’s move

A rocky ride on Easthampton’s Union Street: Businesses struggling with overhaul look forward to end result

A rocky ride on Easthampton’s Union Street: Businesses struggling with overhaul look forward to end result

‘None of us deserved this’: Community members arrested at UMass Gaza protest critical of crackdown

‘None of us deserved this’: Community members arrested at UMass Gaza protest critical of crackdown

Guest columnist David Narkewicz: Fiscal Stability Plan beats school budget overreach

Guest columnist David Narkewicz: Fiscal Stability Plan beats school budget overreach

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field

Northampton’s lacrosse mom: Melissa Power-Greene supporting Blue Devils on and off the field

Reporters loved Marble’s athleticism and sunny California looks, employing plenty of comically sexist copy in their stories, like one that called her “the fair-haired, green-eyed queen of American tennis … one lady athlete who is a sight for sore eyes.”

Marble’s career was largely derailed by history’s greatest conflict, as WWII shut down competitive tennis for several years, just as she had reached the top of her game; she did play exhibition matches, often for U.S. troops, during the war.

And after the war, though she had successful stints as a public speaker, tennis columnist, and clothing designer, Marble was eventually forced to take on more routine work — including a stint as a bartender — to make ends meet, at least in part because of limited job opportunities for women.

“She didn’t have a lot of resources to fall back on,” said Blais. “She was single, and she was a woman, and that just made things harder.”

Marble would distinguish herself in other ways, though, most notably through an open letter she wrote in 1950 in a tennis publication in which she called for a promising African-American player, Althea Neale Gibson, to be allowed to compete in the U.S. Open, which had never included Black players. (Gibson went on to win several major tennis titles and was named Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press in 1957 and 1958.)

Marble also revolutionized tennis for women, pioneering an aggressive, serve-and-volley style of game that made her, as one newspaper wrote in 1939, “the first woman to play tennis like a man.”

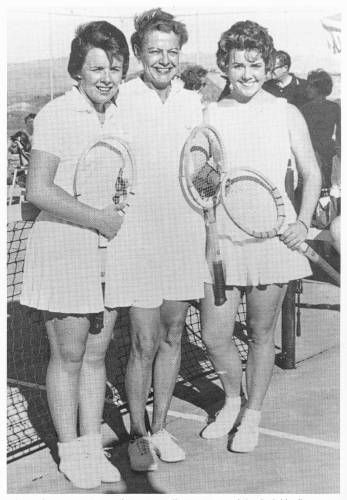

Years later she would coach a teenage Billie Jean King, who remembered Marble as a big influence on her own style. “Alice Marble was a picture of unrestrained athleticism,” King said.

“Queen of the Court” also offers an intriguing look at tennis in the early 20th century — an era when there was no prize money for winning tournaments — with mini-portraits of players like Bill Tilden, a young Bobby Riggs, and Marble’s chief competitors such as Helen Jacobs.

But at its heart is Alice Marble, a charismatic figure who in her later years told stories about her background that seemed to raise questions about her truthfulness, perhaps because, as Blais notes, she was trying to hang on to the vestiges of her celebrity, or deflect questions about her sexuality.

“She lived many different lives, and she had many contradictions,” said Blais. “She was strong and tough in a lot of ways, but she also had a lot of fragility.”

Marble, born in rural California in 1913 but raised primarily in San Francisco, faced lean times growing up. Her father died when she was six, leaving her and three of her siblings to be raised by her mother and her oldest brother, Dan, who left school at 13 to support the family.

The tomboyish Marble excelled at sports, first in baseball and then in tennis after Dan convinced her playing tennis would be more feminine. She quickly won notice as a talented though sometimes headstrong and undisciplined regional player.

That changed after she met tennis coach Eleanor “Teach” Tennant when she was about 17. Tennant took Marble on as a kind of personal project, greatly improving her playing but also strictly controlling her life, almost like a chaperone.

Since Tennant also gave noted movie actors tennis lessons, the young Marble was introduced to stars such as Carole Lombard, who became a good friend (Marble also once had a Hollywood screen test). Yet her social development may have been hampered by her celebrity-colored but closely controlled life, Blais notes.

“I could never decide if Teach was ultimately a good or bad influence on Alice,” she said. (Marble would part company with Tennant in the mid 1940s, writing later that she told her coach “I’m a person, not a trophy for you to show off.”)

Yet some of these accounts, many of which appeared in a 1991 memoir, “Courting Danger,” that Marble crafted with journalist Dale Leatherman, have left lingering questions. (Marble died in 1990, not long before the book appeared.)

For one, Marble said she had either been engaged to or had married a man identified only as Joe, a reported U.S. Army intelligence officer who Marble said had died in Europe at the end of WWII. In some of her accounts, she also said she’d suffered a miscarriage during their time together, or that a child they had adopted died in early adulthood.

Marble also claimed she’d served as a spy for the U.S. in Europe at the end of the war, investigating Nazi plunder allegedly being passed through Switzerland. The former tennis star said she’d been shot in the back doing this work, narrowly escaping death.

It’s a story, Blais says, that doesn’t seem to hold up to scrutiny but can’t be disproved outright, either.

“It’s hard to prove a negative,” said Blais, who notes that Marble seemed to embellish other parts of her background as she got older. “The best I can do is leave this as a nuanced discussion for readers.”

Marble’s story ended on a sad note, as she died alone in a small, nondescript house in Palms Springs, California after many years of heavy smoking and drinking.

As Blais writes, “History never favored Marble. Not after she became the most decorated woman in tennis for her time — just as the whole world went dark.”

But “Queen of the Court” is full of indelible scenes of just how lively and unconventional a person she could be. Billie Jean King recalled Marble teaching her when she was a teen, offering her valuable corrections and tips on court — in between puffs on a cigarette.

In an essay she wrote for the online news site AIR MAIL, Blais says her feelings about Marble ranged widely while working on her biography, from “awe to frustration, from an impulse of protectiveness to wanting to shake some sense into her.”

But, Blais adds, “Deep admiration won out in the end. The more I learned about this complicated, fragile, accomplished, witty, resilient, brilliant, talented woman, the more I wanted to know.”

Madeleine Blais will discuss “Queen of the Court” at Amherst Books on Nov. 6 at 6 p.m.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

![Publisher’s Weekly calls Madeleine Blais’ “Queen of the Court” an “enthralling biography … [that] will likely stand as the definitive account of Marble’s life.” Publisher’s Weekly calls Madeleine Blais’ “Queen of the Court” an “enthralling biography … [that] will likely stand as the definitive account of Marble’s life.”](/attachments/43/42045043.jpg)

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets

Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season

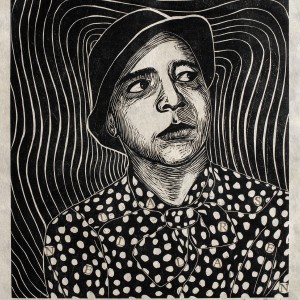

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past

Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past