Comerford’s ‘blue envelope’ bill clears Senate; would guide how police interact with people with autism

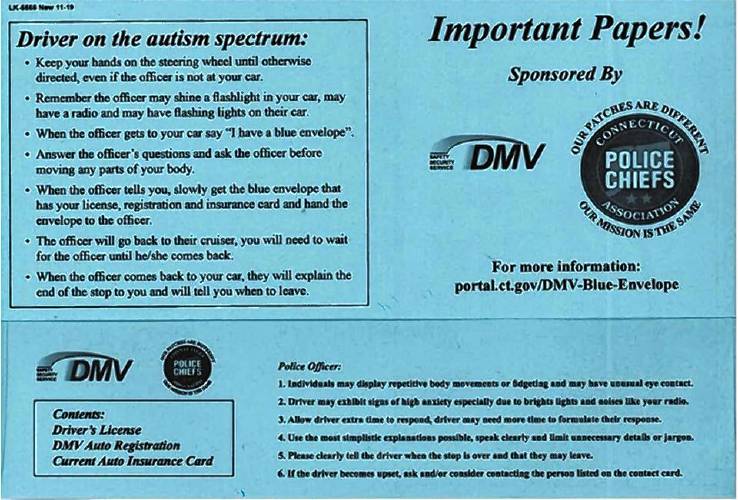

The Massachusetts Senate on Thursday approved the “blue envelope” bill sponsored by state Sen. Jo Comerford, D-Northampton. The voluntary program would make available “blue envelope” to hold the driver’s license, registration and insurance cards of a driver with autism. Connecticut has a similar program shown here. CONN.GOV

| Published: 01-04-2024 4:33 PM |

BOSTON — The Massachusetts Senate unanimously passed three bills during its first formal session of 2024 on Thursday, including the one dubbed “blue envelope” filed by Sen. Jo Comerford that would require new guidance on how police officers should interact with people with autism.

The other bills would make fentanyl test strips legal as a way to protect people from what state public health officials have said is a “poisoned” drug supply, and an expansion of wheelchair warranty protections for people with disabilities.

Comerford’s bill (S 2204 / H 2259), co-sponsored by Rep. Kay Kahn, would create a voluntary program to make available “blue envelope” to hold the driver’s license, registration and insurance cards of a driver with autism. The bill also tasks advocates, chiefs of police, and the Registry of Motor Vehicles to create guidance for officers that will appear on the outside of the envelope.

Other states, including Connecticut, have similar programs.

Drivers with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have a particularly challenging time during police stops and can end up in dangerous situations, disability advocates say.

Autism is associated with communication and social interaction difficulties. Some people on the autism spectrum exhibit repetitive behaviors, sometimes called “stimming,” such as hand-flapping, body rocking or repeating certain phrases. These behaviors can escalate if a person is agitated or anxious.

Without training, police officers can misread the actions of an individual on the autism spectrum and use force in a situation where it could have been avoided, advocates say.

Marie Zullo, a Norfolk mother of an adult child with autism, recounted a story of her son being pulled over to lawmakers during a June hearing.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Pro-Palestinian protesters set up encampment at UMass flagship, joining growing national movement

Pro-Palestinian protesters set up encampment at UMass flagship, joining growing national movement

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Island superintendent picked to lead Amherst-Pelham region schools

Sole over-budget bid could doom Jones Library expansion project

Sole over-budget bid could doom Jones Library expansion project

State fines Southampton’s ex-water chief for accepting lodging and meals at ski resort, golf outing from vendor

State fines Southampton’s ex-water chief for accepting lodging and meals at ski resort, golf outing from vendor

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

2024 Gazette Boys Basketball Player of the Year: Marcielo Aquino, Amherst

2024 Gazette Boys Basketball Player of the Year: Marcielo Aquino, Amherst

“Dominic is a safe, conscientious driver, but we worry the unexpected may be his undoing,” Zullo said.

She said her son could panic and become dysregulated, and hit himself or make dramatic statements in a situation with police. He could also have trouble processing what a police officer is saying to him.

“Last June, Dominic was rear-ended in an accident. In a panic, he started to apologize for an accident that was not his fault. He paced toward the highway traffic, his voice getting louder as he became dysregulated,” Zullo said. “Fortunately, my husband was with my son and was able to keep him safe, though was having trouble calming him.”

Her husband told the officer at the scene that Dominic was on the autism spectrum, and the police helped calm her son down and understand what had happened, Zullo said.

The Massachusetts State Police Association and a representative of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association testified in favor of the bill during the June hearing.

“Massachusetts police officers conduct thousands of traffic stops each year. While most of these interactions are relatively routine, officers do not know who they are interacting with before the traffic stop so they proceed with caution,” UMass Amherst Police Chief Tyrone Parham said in a statement about the bill.

He continued, “The introduction of the blue envelope under these stressful interactions will provide immediate information and context to the officer as they begin to communicate. Traffic stops are some of the most dangerous citizen interactions by police and this additional informative information gleaned by the blue [envelope] will be extremely helpful.”

Comerford said some police departments began using the blue envelopes in their towns after local advocate Max Callahan, who has autism, began pushing for Massachusetts to start the program. Deerfield Police Chief John Paciorek “took it into his own hands” to use the system after meeting with Callahan, Comerford said.

This is the second time she has filed the bill, but the Northampton Democrat said “it’s an idea whose time has come in Massachusetts.”

“Having a visual reminder that someone may communicate in different ways and that someone can’t just jump to an assumption about behavior, communication, eye contact or body language ... this could help both first responders and people with autism have an understanding and see each other as more human,” Comerford said.

The bill has wide support from Autism Spectrum Disorder advocates around the state, including the Arc of Massachusetts and Advocates for Autism of Massachusetts (AFAM).

“This bill will ease interactions between police and autistic drivers, ” said Maura Sullivan, director of government affairs for The Arc of Massachusetts. “We know these situations can escalate and become traumatic or even dangerous.”

Ilyse Levine-Kanji, an executive committee member of Advocates for Autism of Massachusetts (AFAM), called the bill a game-changer.

“Like many people with autism, my 25-year-old son Sam does not have any physical characteristics that indicate he has autism,” she said. “In a stressful situation, where split second decisions must be made, I’m relieved that a police officer could see a blue envelope in Sam’s car and immediately understand that any unusual behavior or speech pattern is a result of autism.”

Sen. Cynthia Creem said the chief of police in her hometown of Newton first approached her about fentanyl test strips, saying that they are an important overdose prevention resource but are illegal in the state.

“They’re highly effective, easy to carry around, everything is right, except it’s considered drug paraphernalia in Massachusetts,” Creem said.

The testing strips can warn people if drugs or pills they plan to use contain the potentially deadly synthetic opiate that has infiltrated drug supplies across the country, fentanyl.

To test for fentanyl, a person can dissolve a small amount of cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin or other drug in water, then dip a test strip in the solution. Results take two to five minutes, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Fentanyl is similar to morphine but 50 to 100 times more powerful, the National Institute on Drug Abuse said, and oftentimes people do not realize it is in the drugs they are using. The synthetic opioid began being recorded as responsible for an increased amount of drug-related deaths about a decade ago.

Individual test strips are about $1 each, but states where they are legal also commonly have community programs that give the test strips out for free. Since 2022, 16 states have legalized the tool, Creem said.

Under Massachusetts law, possession or sale of drug paraphernalia is punishable by up to two years in prison or a fine of $500. The definition specifically includes “testing equipment used, primarily intended for use or designed for use in identifying or in analyzing the strength, effectiveness or purity of controlled substances.”

Creem’s bill also includes an explicit good samaritan provision that exempts criminal or civil liability for “any person who, in good faith provides, administers, or utilizes fentanyl test strips or any testing equipment or devices solely used, intended for use, or designed to be used to determine whether a substance contains fentanyl or its analogues.”

The wheelchair warranty bill would require every wheelchair sold or leased in Massachusetts to come with at least a two-year warranty. During the warranty period, manufacturers would be required to provide a remote assessment for a defective wheelchair within three business days and an in-person assessment four business days after that. If an individual needs a temporary loaner wheelchair, the manufacturer would also have to provide one within a few days.

This bill would catch Massachusetts up with other states, Cronin said. Rhode Island and Connecticut require two-year warranties for wheelchairs. Massachusetts currently has a law requiring manufacturers to provide warranties to some individuals, but it is limited in scope. It only mandates a year-long warranty, doesn’t apply to all wheelchairs, and there are no current requirements on how quickly manufacturers must respond.

“It’s a bread and butter consumer protection bill that is going to be impactful for a population that is really vulnerable and the laws need to be strengthened to protect right now,” Cronin said.

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue

Pro-Palestinian encampment disperses at UMass, but protests continue Amherst council confirms Gabriel Ting as police chief

Amherst council confirms Gabriel Ting as police chief Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city

Music key to Northampton’s downtown revival: State’s top economic development leader tours city