Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: What good is an herbarium? Herbariums, like Emily Dickinson’s, are an essential resource for scientists

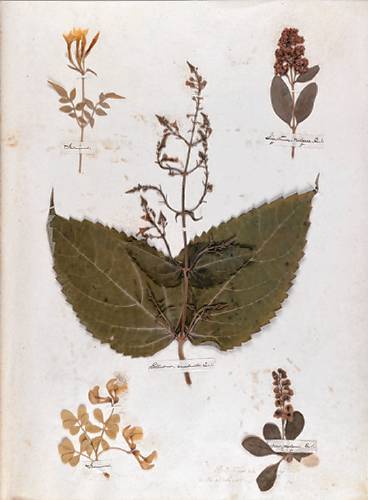

A page from Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. HARVARD UNIVERSITY/HOUGHTON LIBRARY

| Published: 04-05-2024 2:01 PM |

The word “herbarium” sounds a bit quaint, even antiquated. We may think of Emily Dickinson’s herbarium, which she created during her year at Mount Holyoke in 1847-48. Although she had begun studying plants at age 9 and was helping her mother in the garden at 12, it wasn’t until she went away to school that she started a serious study of plants. At Mount Holyoke, compiling an herbarium was a required part of the botany curriculum until 1910. Students were expected to collect at least 300 different specimens. These were dried and mounted on stiff paper, with their names, location and other pertinent details affixed. Collecting plants was one of the only activities students were permitted to do while taking their daily, mandatory one-mile walk. Mount Holyoke founder Mary Lyon kept an herbarium, along with botany professors Lydia Shattuck and Henrietta Hooker, both Mount Holyoke graduates.

Dickinson’s herbarium was particularly fine. She collected and pressed samples of 424 local plants, which she called “beautiful children of spring,” and pasted them artfully across the 66 pages of her leatherbound album. She added labels for each with their common and scientific names. As anyone familiar with Dickinson’s poetry knows, plants were a lifelong source of inspiration for her. The herbarium is now locked in a vault at Houghton Library at Harvard University. It’s so fragile that it’s off limits to almost everyone. But owing to the widespread interest in the Amherst poet’s herbarium, Harvard had it digitized in 2006. It can be viewed at: https://library.harvard.edu/collections/emily-dickinson-collection

But herbariums are not just hobbies for plant enthusiasts. They have been around for hundreds of years, often created by botanists who go on expeditions to collect new plants, seeds and stems to study and preserve for future research. Because herbariums contain plants collected over long periods of time, they provide valuable information about the effects of human activity on the environment. Of particular significance these days, herbariums are an essential resource for scientists seeking to understand threats to biodiversity, preserve endangered species and respond to the many threats of climate change.

Herbariums have become even more useful as technology has advanced. DNA sequencing has allowed researchers to extract genetic material from dried specimens, enabling them to trace plants back through the millennia. Some collections have shown that plants have shifted their ranges to adapt to a warming climate. And herbariums continue to add to their collections, often preserving endangered species that are facing extinction.

Given the increasing value of herbariums in our environmentally challenged world, the scientific community was shocked and dismayed by the recent news that Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, is planning to close its herbarium, one of the biggest and most diverse in the country. Established in 1921, the Duke herbarium has 825,000 samples of plants, algae and fungi. Duke, which has an endowment of $11.6 billion, claims it can no longer afford to maintain the herbarium and is looking for a new home for the collection.

Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done. “There are no herbariums that could absorb something like this,” said Kathleen Pryer, the director of the Duke University herbarium, in a New York Times interview. “I’m very concerned that it will end up in a warehouse somewhere and become forgotten.” Given the fragility of dried plant materials, that would likely be a death sentence.

It’s true that maintaining an herbarium as large as Duke’s is a costly enterprise, but scientists everywhere agree that Duke’s cost-cutting decision will have serious repercussions for Duke’s well-established academic research on the diversity of plants. It’s an about-face for the university, according to the Times, which reported that as recently as last March, the university boasted about the climate research performed at the herbarium in a promotional video.

And Duke isn’t the only university to close its herbarium. In 2017, the University of Louisiana Monroe cleared out half a million specimens to make space for new sports facilities. These were saved at the last minute when various collections offered to take them.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Scientists and scientific societies have protested this development. “Duke’s decision to forgo responsibility of their herbarium specimens sets a terrible precedent,” the Natural Science Collections Alliance wrote in a letter to the university. According to the Times, this alliance, along with six other scientific societies, has endorsed a petition asking Duke to reconsider closing the herbarium. As of March 20, it had gained over 17,000 signatures of the 25,000 it hopes to gather. (If you’d like to add your name to the petition, click on the link above.) We can only hope that Duke will do the right thing and continue to support its world-class herbarium, not just for scientific posterity but for the future of the planet.

Mickey Rathbun is an Amherst-based writer whose new book, “The Real Gatsby: George Gordon Moore, A Granddaughter’s Memoir,” has recently been published by White River Press.

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College

The power of poetry: U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón to speak at Smith College Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how