The gang trap: Two stories of striving to make a life in and out of gangs, jail and prison

| Published: 07-06-2016 3:32 PM |

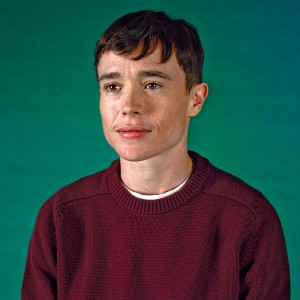

Ricky Aviles and Christian Lopez, two men with histories of gang activity in Holyoke, were recently released from jail in Franklin County. They spoke of their lives and challenges with Gazette collaborator Revan Schendler.

When I was around 8 years old, I was coming from my aunt’s house, we were driving down the street and my mother was talking about all the gangs. She was saying that it wasn’t a life, carrying a gun every day, looking around to see if someone was going to shoot you.

And as she’s talking, we see this guy wearing all red. He has a hat on, and when he turns his face to look at the car, he has a tattoo on his face that says ADR, Amor de Rey, and he has a spider on the other side of his face, tattooed, and he has this big lump on his waist. He’s just walking down the street. And my mother’s telling me not to look, to look away. And we continue to drive off.

That was the first time I encountered Ricky. — Christian Lopez

...

Recently I had a visit from my father. It blew me away to see him. I haven’t seen him for two years. I had so many questions, so many things I wanted to ask him about, but I just took that moment and enjoyed it. I didn’t think about nothing negative, I was happy he was there, we talked, we laughed, it was cool. I didn’t want to spoil the moment. I tend to spoil moments instead of cherishing them.

When I was growing up, we weren’t close. It’s a relationship I don’t want to have with my own kids. I don’t want them to be distant. I’m taking a Nurturing Fathers class at the Recover Project in Greenfield, and one thing I’m really getting out of it is how to be patient with my kids as a father, to listen to them. To make our relationship about them, find out what issues they may have, even if it’s about how I am as a father.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College

South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College

LightHouse Holyoke to buy Gateway City Arts, expand offerings and enrollment at alternative school

LightHouse Holyoke to buy Gateway City Arts, expand offerings and enrollment at alternative school

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

South Hadley man fatally shot in attempted robbery

South Hadley man fatally shot in attempted robbery

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

Area briefs: Transhealth to celebrate 3 year; Holyoke to plant tree at museum; Documentary film about reparations focus of Unitarian talk

Area briefs: Transhealth to celebrate 3 year; Holyoke to plant tree at museum; Documentary film about reparations focus of Unitarian talk

I haven’t really had a chance to do that, to be with them much, because I’ve been locked up for so long. Basically how to communicate, like how to get out of them how they’re doing. You ask and they’re like, fine. No, how are you doing? What was your day like today? What if anything bothered you today? Just learning how to communicate and be patient with them.

As a kid I never sat down with my mother and told her how I felt. I never reached out to my dad and told him how I felt. I kept my feelings to myself and searched in the streets for a way to fill the emptiness. You have to have an open line of communication with your parents, but it’s hard. You feel like you’re grown, but you’re not, you’re 13 or 14. — Ricky Aviles

...

Christian Lopez: My father being incarcerated for 15 years—that really affected me. When I was about a year old, he got caught with my mother. My mother ended up doing a month in jail. I ended up living with my sister at my aunt’s house. My dad got ratted out by his cousin, so they took by dad away from me. I had older brothers, but they didn’t treat me like family, so I didn’t have a male figure there for me.

My father was more of a hustler type. He was humble, just trying to make a living selling drugs. I thought my father was this big macho man in the street, but when I found out what he was I didn’t want to be like that, I didn’t want to be taken advantage of, period. I wanted people to know I meant business.

...

Ricky Aviles: Growing up in Chicago, all I could hear was gun shots, fighting, rumbles. It was all gang-related situations. And I learned my father’s youngest brother was gangbanging, so I tried to figure out how I can be around my uncle more, find out what he’s doing, without him trying to jump down my throat. He lived with my grandmother, and I was just a nosey kid, so every time I was at my grandmother’s house, I’d rummage through his stuff and see his tags, his gang name, on his notebooks and stuff, and that’s when I got concrete evidence.

My uncle does not know that I followed in his footsteps, that he’s the reason I became who I am. I’ve never shared it with him. It would be a burden. He’d probably feel guilty as hell right now if he were to know the reason I turned out this way. I was always locked up. The times that I got shot or when I was the victimizer, or the times I was selling drugs and gangbanging, was because I wanted to emulate him. I wanted to look in the mirror and find him on the other side.

I wouldn’t want him to be like, you destroyed your whole life because you wanted to be me? We’re going to have that conversation, we’re going to sit down, but it’ll be a conversation where I get to thank him for unintentionally showing me that life, because had I not known that, where would I be today? I feel like I had to live that life in order to be able to tell a story that would change the minds of these youngsters who think that gangbanging is cool. I’m trying to change who I am.

I had this big reputation. At the end of the day, I would change it all.

...

Christian Lopez: As a kid, I loved school and I was smart. I wanted to be a scientist. I loved science, chemistry and stuff. I played sports. I was going to after-school programs. Once I turned 15, everything went downhill. I tried to go back the third time to do the freshman year, but I knew I was done. I was making more money than what the teachers made. Even though I didn’t have a license or registration, I had a nice car. I was doing good, according to my eyes.

...

Ricky Aviles: In my teens I ended up moving away from Chicago, so there was no more uncle. It was a real culture shock for me to move to Northampton. I’m a city boy. My family broke up and all of a sudden there was just me. My twin brother’s living in Connecticut with our father, I’m living with my mom in Northampton, my other brother is living with his grandmother in Puerto Rico, my other brother’s living with his godmother in Puerto Rico. I was the only kid in the house and I was bored, so I hit the streets to look for things to do, people to hang out with. My mother couldn’t deal with me. I was disrespectful and didn’t care.

Soon as I moved out here in the summer of ’93, when I was 13, I started getting into trouble. By ’94 I was already getting locked up, and once I got locked up, that was it. And that’s what my whole life’s been, up until today. I’ve been in so many situations, I’m lucky to be alive.

A good friend of mine took me for the first time from Northampton to Holyoke—on a bike! I went with him not knowing where we were going. That was the worst ride ever. But when I got to Holyoke, it caught my attention. It was mad ghetto, the hood. That’s what I’m used to, the ghetto and the craziness. And I thought, I got to come here more. My friend is doing a life sentence in prison today.

...

Christian Lopez: Everybody I care about, really, except my mother and my sisters, every male figure I’ve cared about in my life is in jail or prison, or has led a life that has led them to jail repeatedly. So we find ourselves in the streets after jail and we’re talking about jail. I guess this is the only place we can live, really. Some people turn to gang life, some people turn to addiction, more turn to hustling. We don’t have time to talk about life, talk about what we want to do, because we’re so caught up in what we’re doing now, trying to survive.

I have a bunch of cousins upstate doing life. They did all that in the ’90s. And I’ve got my Cambodian cousins, and they’re doing life as well, 16, 17 years.

...

Ricky Aviles: I found myself going to Holyoke, and that’s when I got involved. I assured myself, if I can’t be who my uncle is, I can be better and bigger, and I succeeded. I’m very competitive, even things that have nothing to do with sports. Once I got that feeling, that these are my brothers, they’re my people, they’re always going to have my back, I started having this sense of power, and I had my chest out, like I’m the man. And I didn’t want that to go away, who does, when you’re growing up and you feel like you’re the man, you’re the one. Nobody could take that away from me.

My best friend, Johnny Blaze, got killed in March 1998, in Holyoke. That messed me up. He was 18. I was 17.

...

Christian Lopez: I met this old Rastafarian dude from Connecticut, and he had all these tattoos of the Black Panthers. He’s like a freedom fighter. He was explaining to me that before it broke into two street gangs, the Bloods and the Crips, in the 1960s, it was a political party. It was about fighting oppression. Breakfast programs for kids, health clinics, all for poor people. This was a beautiful thing that people turned into something that was wrong. I was mesmerized.

Then he told me the savage part of it, that they’re known for their brutality, they’re always low in numbers and always outnumbered, which is what makes them vicious and cunning and everybody be afraid of them, and that’s what really sparked my inspiration, everybody being afraid.

I was into being a macho man. That’s what I saw in Ricky. I knew from my mother—the way she was talking about him that day when I was a kid in the car, how she told me to look away, she didn’t want me to look at him, like basically shade your eyes, look away—I knew he was the one.

...

Ricky Aviles: I never had no one to tell me, yo, what are you getting out of that? Instead, there was always encouragement. You’re the man! Take over! So I was into all that. And really, I couldn’t be told nothing.

Every day I regret what I’ve done gangbanging and running them streets. It took from me the ability to be a good father, a good son, to be somebody. Of the last 22 years I have spent roughly 16 inside. This has made me institutionalized. I tell myself that my experience of being locked up for so long has some value if I can help someone avoid the life I have lived.

I’m sure there are a lot of programs out there that provide for young people, but not everyone has access to them. Many people in the corrections system grew up in broken homes or the foster system. It’s easy to blame abusive or neglectful parents, people who have a bad influence, or the neighborhood. I think the real blame should be placed on communities who don’t care about our youth.

...

Christian Lopez: I was smoking with some guys when I was around 14, and there was an off smell in the room but I didn’t think too much of it—I thought it’s probably just some regular stuff that stinks nasty. And then it hit me. My face got numb, my hands got numb, everything got numb and I couldn’t feel if I was high or not, didn’t know if I was high or not.

It was soaked in PCP, embalming fluid. On that drug you don’t feel any emotion—none of the remorse or the love or anything that you feel for somebody. So it was like, I can do anything without emotion.

I was a machine, basically. When I found out what it was, I just kept smoking it and then after I kept smoking it I saw the effects, like I can’t feel my face, I can’t feel my arm, I hurt myself, couldn’t feel it, I’d slam my hand into a door, I couldn’t feel it. I couldn’t feel anything.

And then I’d do things, and I wouldn’t feel it, I wouldn’t feel that rush of adrenaline, I wouldn’t feel anything. So this is what I could do to people now, and I didn’t feel anything about it.

I was addicted to it. What I loved was the no emotion part of it. I have no emotions. I can’t feel any pain. You can do anything to me and I won’t feel it. I can die and not feel it. If I could die right now, I wouldn’t feel it.

I guess I wanted to die, by the actions I was taking. I never thought I’d make it to 22.

...

Ricky Aviles: You find yourself alone inside, you got no money, you’re striving, sometimes you’re hungry at night and you miss your kids, you start missing your family, you have your regrets. That’s the only time I find myself vulnerable, but I can’t show it.

...

Christian Lopez: The second time I met Ricky I was 15, we’re in this bar in Holyoke. His brother works with my father. I was hanging out with him and I see this guy walking towards us. He’s wearing a hoodie, holding his waist, and my father says, that’s Ricky.

We go to my father’s and we’re sitting there talking, me and Ricky, I’m telling him who I hang out with, I’m telling him what I’m doing. I show him my gun, like I got a gun too, I’m beefing with a couple of dudes.

And he’s saying to me, take care, wear a vest. He was trying to basically school me. We hung out for a while, and he sent me on my way. This is the last time I’m going to see him. Next time, we’re not going to stop and talk to each other. Different streets, different gangs. He’s a stickup kid and I’m a stickup kid. He’s perfected his game and I’m still learning. He’s going for the big fish and I’m going for the fish under him.

When I turned 16 my name started to ring bells.

...

Ricky Aviles: When it comes to Christian, I had no idea. I hadn’t seen him in a few years. He had changed, got older. I went up to him and said, you look familiar. And he’s like, are you serious? Yo, it’s Christian! I gave him a hug and said, you lost weight! When he was younger he was chunky. He doesn’t like me to tease him about that.

We started talking and I sat him down, I started telling him about what I was doing there, that I don’t gangbang no more, and I was trying to change my life. He was like, word? It took him off guard.

And I remember asking him, how did you get into gangbanging, like where did this come from?

And he looked at me and he said, what do you mean? I’m following you. You’re a legend in Holyoke. All the youngsters want to be you.

I thought I had caught him off guard, but he surprised the hell out of me with that one. It brought me back to remembering how much I wanted to be like my uncle. There’s always one generation looking up to another one. That’s the first time that I realized that my ways and my reputation and who I was in that life affected others trying to do the same thing, ruining their lives.

...

Christian Lopez: When I met Ricky in jail, he was walking around I was looking at him and he was looking at me and I’m like, yo, you know me, and he’s like, where do I know you from? And I told him my father’s name.

We went into this side room and he put on this CD with beats on it and we started listening to the beats and we just started talking, and I told him how his format and the way he did things was the way I was trying to be, was how I had become. I had attained it.

Ricky was like the LeBron James of gangbanging. He was the one who was doing things. He was feared but he was also loved. He’d say something and the next day or the next minute it would be happening. I like that decisiveness, that cunning, that planning ahead.

I was learning from him on the streets and I’m still learning from him.

...

Ricky Aviles: My last state bid I wrapped up June 28, 2013. I was only out for 49 days. It’s hard for me to talk about, because I don’t like to admit it. When I’m locked up I don’t think I have a problem. When I get out, I’m aight, but then I’m not aight, because I fill out job applications and the first thing they do when they see me is wonder what I’m doing there, covered head to toe in tattoos. So I can’t find a job, I start stressing, I go back to selling drugs, and when I sell them I start doing them too, because they’re right in front of me.

So that time, I was triggered, started using drugs again. I didn’t care about nothing, not even my kids, I didn’t care about myself, got rid of my phone. I didn’t want no contact with nobody. I just wanted to get high.

They gave me a year for the violation, and in that year I thought about the time I had spent with my kids. I wasn’t thinking about my recovery as an addict. That only started when I got here. I’m scared to get out, actually.

I have taken advantage of every program while incarcerated at the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office, including college classes and treatment for drug addiction. My mindset has made a tremendous change I thought would never happen and I am 35 years old. It took me a while to get the hint.

But I’m still scared.

...

Christian Lopez: He told me, I’ve been through everything you’ve been through, and look at me now. I don’t have a dollar from then, I don’t have a car from then. Nobody comes to see me. They don’t help my mother out. There’s no point in this. This gang life is worth nothing. Me and you have wasted almost 60 years of our lives doing nothing. It’s not worth it. We’re fighting for a cause that’s never going to do anything for us. The block, the street that can never be yours, a color that can always be disrespected and can always be thrown on the ground, something than can never be uplifted: that’s the cause we’re fighting for.

Doing all those stunts on the street, Ricky said, now I have to look over my shoulder. And if I’m not looking over my shoulder, I’m making the next person look over his shoulder. I’m living in fear, and the next person is living in fear because I’m around.

Look at me now, he said. I have a bunch of tattoos on my face, I can’t get them off. I don’t regret it, because there’s no point. They’re there. I did it for a reason at the time.

All that really hit me.

...

Ricky Aviles: What can I do? I showed him the way in. Now how do I show him a way out? Forget everything you’ve ever known.

In the life, it’s all about getting that money, being with the boys, the girls. How can I come in the middle of that and be like, no, you got to get a job, you got to go to school, you got to live your life this way? Everyone needs models to look up to as you strive to figure out who you are, a feeling of hope and belonging. If you can’t find hope and love in your own family, maybe you’ll look for it in a gang, crew, or other organization. I found it in a gang.

Christian says to me, you did it all these years and you’re saying I shouldn’t do it? Are you a hypocrite? Other times he listens, and he agrees, but I can see right through him. That kid scares me.

Sometimes I catch him saying stupid stuff. It pisses me off and I say to him, stop letting that stuff entice you! You get all amped up talking about the street. You can’t do that stuff! And he’s like, I know, I know, but—

But nothing. You got to stop that now.

I get it. Sometimes that stuff entices me, too.

He says, yo, I want to do the same thing you’re doing. I want to go to school with you. Do you know how many youngsters follow you today? If you go out there with this, you are going to be the reason things change out there.

I tell him, I can try, but right now I’m working on you. I tell him, stay working. Go to college or something with me, man.

Ever since he said he’s trying to follow me, I’ve been like, well then you’re stuck with me. I’m not going to let you continue on. I stopped. Something happens to you, I’m going to feel like it was my fault.

That’s why I never told my uncle. I don’t want him to feel the way I feel right now. I’ll tell him now that I’m older, and changing my life, and I’m different, and I can actually be honest but also let him know what good came out of that, as opposed to Christian telling me, and then staying in. Now I have to think about that, carry that burden around.

...

Christian Lopez: I felt let down, disappointed, like I just did all this for nothing, I ruined my life for no reason. I tried to give myself a reason, like I wanted to be that person, the top dog, I wanted to be the one everybody feared.

Ricky kept talking. He was like, what did you get out of that, everybody being scared of you and one day someone coming up to you and shooting you out of fear?

I was hot and sweaty. I couldn’t believe it. My mind was racing and I was starting to get frustrated.

And he’s like, there’s no need to get frustrated. You can go through it, but there’s no need to be frustrated. Me and you are talking about it so we can get it out here, right now. I’m telling you it wasn’t worth it, so you just need to let it out.

So I told him how I felt.

...

Ricky Aviles: I think it has to do with poverty, lack of opportunity, why we all got involved. And then it’s like everybody’s mind is made up. Doors are closed. This group is racist and there’s no changing that. This group stereotypes people. Everybody’s stuck in their certain way. ...

If we are a country that values equality we should do something about the lack of opportunities for young people from poor families. We should give young people the support every person needs to find their way in life, not push them into the system and forget about them. We need more role models, more interacting with others, more schools, more sports and recreational activities, more opportunities to see a world outside the bubble, the violence. Without opportunity you can end up in prison or dead, especially if you are poor or a young person of color.

Schools know which kids are doing good, and they know which kids are acting out for that attention. They have to grab those kids in elementary school and give them the support they need. Don’t lock them up! That’s how I met some of my boys: in juvie.

...

Christian Lopez: I have this little kid who looks up to me. I love this little kid to death. I’ve watched him grow up. And he ended up getting down with my gang, and for some crude reason I was happy for him, like yes, this is the right choice for you. But after seeing what’s been going on with him, it’s like, this was never meant for you, I mean, I should never have told you to get down.

Now he’s out there just trying his best to stay alive. He’s a fighter kid. He’s going through it out there, and he has no mother. His mother deserted him. His sister’s trying to keep the family together the best she can. His little brother is following in the same route. This little kid is very smart, and they’re just out there living from house to house.

I feel like I caused that. I feel like it was my fault. Even though the situation with his mother would have already happened, it could have been better for him. He didn’t have to be a gang member. He didn’t have to look over his shoulder. He could have gone to his boxing class without having to be scared of dying. He’s out there right now with nowhere to live, sleeping on someone’s couch.

He says, I’m just looking up to you, I’m doing what you’re doing, this is what you wanted to do, and I want to do what you did. And if I try to say anything to him, he throws that in my face. Like you did it, why can’t I? That really hurts me.

And I’m realizing, I’m going through the same situation with him as Ricky is going through with me.

...

Ricky Aviles: My best friend who was killed when he was 18 was a good kid. Smart. Didn’t have kids. He left three brothers and two sisters. The smallest one I used to see running around barefoot, hyper as hell. I’m like, can you put on some shoes on and stay still?! He was upstate with me, how about that, doing seven years. Stuff like that messes with me, how time goes by and all the years I’ve been locked up and here I’m seeing the younger generation coming up, and they’re all gangbanging.

I try to stay away from thinking about those I have lost to violence. There are too many of them. Willie, Timmy, Minus—haven’t thought about them in a while—Greg, Xavi. I was watching the news when that one popped up. Kayla, Lissy. There are so many more.

...

Christian Lopez: Recently my cousin was shot five times. He felt the first one, but the rest knocked him out. He said he lost a couple quarts of blood, so he’s really skinny. He’s still got two bullets lodged in his back. I asked him, is revenge in your plans, or are you just going to let it rock? He’s like, really, dude? I got PTSD, I’m going to a shrink, I can’t see cars pass by me. I said, I love you dude, it’s either one or the other, either we get out of the game now, or we continue to play the game. He just stood quiet. He didn’t really have an answer.

...

Ricky Aviles: I got stabbed four times on one occasion. Two years later I get shot. Two years later I get shot again. Two years later I got shot again! All from 17 to 23. Six years I went through that.

Look at Christian’s cousin, shot five times, lucky he’s walking around. Paranoid, skinny as hell, scared, thinks he’s going to get shot. It’s sad. He’s traumatized, messed up in the head.

I say to Christian, take heed, man. Don’t think you’re invincible, unstoppable. Next time, one bullet might be enough.

...

Christian Lopez: A gangbanger is someone who’s out there trying to make a name for himself, a name that will never amount to anything, never get you a dollar, never get you your family back, never get the time you spent in jail back, none of that. My name is worthless.

It takes a toll on you, gangbanging and hustling and trying to get money to take care of your family. When you’re by yourself you’re thinking about everything that’s happening and your emotions take over and you’re sitting there stressing and you have to go out in the world and be heartless. You’ve got to dodge other gangs, be stone cold. When you want to be vulnerable, you can’t be. You always have to be on top of your game or you’ll get killed.

Basically in the front of my mind is, Trying to change, trying to change, trying to change, but in the back of my mind it feels like I’m going to go out there and do the same thing again, like I’m trapped in this life that isn’t a life. ... Next time I see my so-called brothers, they’re going to tell me, your work isn’t done. You have your whole life ahead of you. You can stop when you’re old.

That’s what they’re going to tell me. You stop when you’re old and we can’t use you no more.

...

Ricky Aviles: When I’m locked up, I’m bummed out. I think life is unfair and unjust—it is—and that’s what goes through my mind. Right now I’m in prerelease, where we can cook our own food. I cooked some French toast the other day, and being able to do that was like, damn.

To sit down and put some butter on it and cut it up into pieces and put syrup on it and eat it, be excited to tell my mom, Mom, I made some breakfast today—that was crazy! That’s when you know when you’re taking life for granted. I could be out there doing this for me and my kids.

And my mom says, for real? I can’t wait for you to make French toast for me. Every time I tell her something she’s so excited. Today I feel life is precious. The little things that I’ve taken for granted, that’s what makes me realize how good life is, in a free way.

Revan Schendler of Greenfield is an

oral historian, writer and editor. She collaborated last with the Gazette on the project “Letters from Inside,” published Dec. 2

and 3.

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis Lora Sandhusen: Discourage ultra-wealthy consumption habits with carbon tax

Lora Sandhusen: Discourage ultra-wealthy consumption habits with carbon tax Guest columnist Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Guest columnist Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said