Organizers ramping up for bigger Northampton Pride this year

NORTHAMPTON — Under new organizers and a nine-week planning schedule, Pride returned to the queer capital of Northampton last year after a three-year hiatus, and it’s back to stay.Hampshire Pride, the nonprofit that revived Pride in the Pioneer Valley...

Crocker School kids draw on historical picture books for library banner project

AMHERST — An unfolded brown paper bag is being transformed, through use of crayons, pencils and paint markers, into a banner showcasing an acclaimed American naturalist, artist and academic.“I think Anna Comstock was very impressive in her work,” says...

Most Read

Editors Picks

All about conviction: PVPA team wins state, heads to nationals of Mock Trial Championship

All about conviction: PVPA team wins state, heads to nationals of Mock Trial Championship

Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries

Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries

News Briefs: Roadwork in Plainfield; bake sale in Hadley

News Briefs: Roadwork in Plainfield; bake sale in Hadley

Three Amherst Regional Middle School counselors absolved of Title IX offenses

Three Amherst Regional Middle School counselors absolved of Title IX offenses

Sports

Jiri Smejkal gets 1st goal, Senators beat Bruins 3-1 in regular-season finale

BOSTON — Jiri Smejkal scored his first career goal midway through the second period and Jakob Chychrun scored less than a minute later as the Ottawa Senators beat the Boston Bruins 3-1 on Tuesday night in the regular-season finale for both teams.Artem...

High schools: Belchertown, Easthampton split dual track meet (PHOTOS)

High schools: Belchertown, Easthampton split dual track meet (PHOTOS)

High school ultimate preview: Amherst, Northampton hoping for big seasons

High school ultimate preview: Amherst, Northampton hoping for big seasons

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

Opinion

Toni Doherty: 2020s essential workers: Oxymoron?

As a school employee, I’ve hesitated to write, expecting judgment for being self-serving. Here’s what kicked me into gear: Jim Bridgman’s March 5 “A Look Back,” 50 years ago: “Salaries at the University of Massachusetts continued to increase at a...

Rachel Vigderman: Area women ending silence over weaponization of rape

Rachel Vigderman: Area women ending silence over weaponization of rape

Timmon Wallis: More funding for Ukraine not the answer

Timmon Wallis: More funding for Ukraine not the answer

Guest columnist Jay Fleitman: Can’t leave Hamas intact

Guest columnist Jay Fleitman: Can’t leave Hamas intact

Business

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

WHATELY — Tea Guys LLC must pay more than $2 million to a Baltimore tea company due to a breach of contract, a Franklin County Superior Court judge has ruled.The small business in Whately was sued last summer by Zest Tea LLC and had two bank accounts...

Black business group presses demand for Amherst relief funds

Black business group presses demand for Amherst relief funds

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

I have just about reached the end of my patience with the winter of 2024. I realize that this may sound a bit strange, especially because we are now in the beginning of spring, but those of us who bore the brunt of the April snowstorm may sympathize...

Obituaries

Geraldine Packard

Geraldine Packard

Northampton, MA - Geraldine Packard, 87, passed away at her home in Northampton on April 13, 2024. Born to Curtis and Mildred (Smith) Chase on September 23, 1936 in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire... remainder of obit for Geraldine Packard

Russell E. Lent Sr.

Russell E. Lent Sr.

[IMAGE]Russell E. Lent, Sr. Easthampton, MA - Russell Eugene Lent, Sr. 89, longtime resident of Easthampton, passed away peacefully on Friday April 12, 2024, at his home. Born in Coshocton, ... remainder of obit for Russell E. Lent Sr.

Floris Cathelineaud

Floris Cathelineaud

Amherst, MA - On April 14, 2024, Floris Cathelineaud Diaz (Abu) was called to Eternal Rest peacefully at home, surrounded by family and friends, at age 96. She is survived by her daughters, Dr. ... remainder of obit for Floris Cathelineaud

Judith Fuhring Seelig

Judith Fuhring Seelig

Amherst, MA - Judith Fuhring Seelig was born April 19, 1950 and passed away on October 21, 2023 Family and friends invite you to a Celebration of Life in memory of our beloved Judith wh... remainder of obit for Judith Fuhring Seelig

Boyfriend accused in slaying of Hampden sheriff’s assistant, former legislator’s top aide

Boyfriend accused in slaying of Hampden sheriff’s assistant, former legislator’s top aide

Revised plan to combat bullying in Amherst regional schools questioned

Revised plan to combat bullying in Amherst regional schools questioned

Wheeling for Healing returns to South Deerfield to raise money for cancer treatment

Wheeling for Healing returns to South Deerfield to raise money for cancer treatment

Sadiq to leave Amherst middle school principal role

Sadiq to leave Amherst middle school principal role

Northampton seeks bids to redevelop former Registry of Deeds property

Northampton seeks bids to redevelop former Registry of Deeds property

Hadley’s Brad Mish, Northampton’s Elianna Shwayder top Hampshire County finishers at 128th Boston Marathon

Hadley’s Brad Mish, Northampton’s Elianna Shwayder top Hampshire County finishers at 128th Boston Marathon

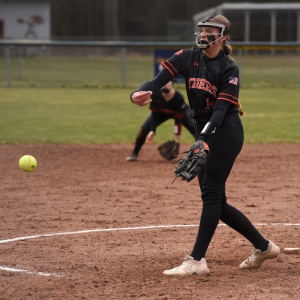

Softball: South Hadley’s Ella Schaeffer records 500th career strikeout in loss to East Longmeadow

Softball: South Hadley’s Ella Schaeffer records 500th career strikeout in loss to East Longmeadow

Two men dump milk, orange juice over themselves at Amherst convenience store

Two men dump milk, orange juice over themselves at Amherst convenience store

Columnist Razvan Sibii: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

Columnist Razvan Sibii: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

High school: Northampton softball slugs past Mahar for season's first victory (PHOTOS)

High school: Northampton softball slugs past Mahar for season's first victory (PHOTOS) Maggie Baumer: Access to prosthetics and orthotics for physical activity a right, not a privilege

Maggie Baumer: Access to prosthetics and orthotics for physical activity a right, not a privilege Recognizing an ‘inspiring force’: City business owner honored with Black Excellence award

Recognizing an ‘inspiring force’: City business owner honored with Black Excellence award Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips

Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke

Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation

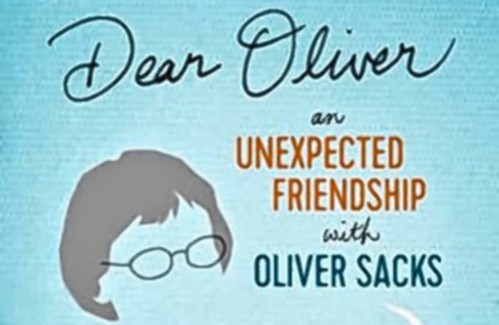

What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin

Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back

Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back