Valley Bounty: Grass-fed animals that feed the grass: Gwydyr Farm in Southampton focuses on ‘restoring the connection between land, food and people’

| Published: 04-12-2024 3:39 PM |

Every piece of farmland has its strengths and weaknesses. Often, the most successful farmers are those that learn to see their land’s potential clearly and — with other things in mind like finances and what customers want — build a business around that potential.

Gwydyr Farm in Southampton doesn’t have the kind of fertile floodplain soils that are great for growing vegetables. But their land can grow one thing really well: grass.

“People can’t eat grass,” says Steven Cowley, one of Gwydyr’s current farmers, “but cows can, and people like to eat cows. And our locally raised meat complements all the produce other farms in the Valley can grow.”

Cowley has been farming for 10 years on his family’s land, which he recently bought from the elder generation, and other nearby parcels totaling 70 acres. At the start, he was literally just farming grass, cutting and selling hay for livestock and horse farms. Then three years ago they started raising beef cattle, and now are adding pasture raised lamb and chicken to what they sell.

The farm’s slow and steady expansion comes as Cowley and his farming partner Caroline Holladay experiment with new farming projects while maintaining the old. All the while, both are still working full-time off the farm at Libertas Academy Charter School in Springfield, where Cowley teaches history and Holladay teaches math.

“Every school break is farm time, and many nights and weekends too,” says Cowley. It’s a lot of work, but breaks in the academic calendar make it manageable. Meanwhile, teaching provides a stable income alongside the farm.

“We realized that owning a livestock farm wasn’t something I could jump right into financially, so for a while teaching has helped pay the bills,” Holladay says. “But we’re both looking forward to expanding the farm until it isn’t just something we do for summers and breaks.”

Gwydyr Farm was originally named by Cowley’s father, a large animal vet whose expertise they appreciate as their menagerie grows. Gwydyr is a Welsh word meaning “wild land,” which Cowley thinks is a fitting description.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

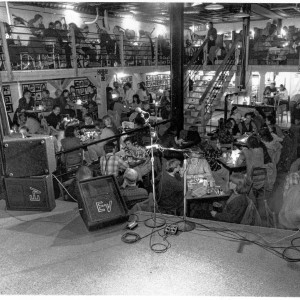

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

The Iron Horse rides again: The storied Northampton club will reopen at last, May 15

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Homeless camp in Northampton ordered to disperse

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

$100,000 theft: Granby Police seek help in ID’ing 3 who used dump truck to steal cash from ATM

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

UMass football: Spring Game closes one chapter for Minutemen, 2024 season fast approaching

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

Final pick for Amherst regional superintendent, from Virgin Islands, aims to ‘lead with love’

“We go from really heavy soils to lighter stony soils,” he says. Some pastures have remained open for years, others are in various stages of returning to forest. As farming operations expand, some of the wilder areas are getting tamed. While Cowley and Holladay are orchestrating it, the animals do most of the heavy lifting.

“They’re our own army of land clearing tools,” says Cowley, “and they love to eat.”

The beef cattle make the first pass, the farmers rotating them throughout the landscape using a mobile electric fence. They clear brush as they eat and fertilize the soil with their droppings, encouraging the grassland species that are best for grazing and haying to grow back stronger. This improves the productivity of the very land that feeds them and sustains the hay business.

Cowley started his herd with different breeds but has since fallen in love with Devon cattle, one of the original breeds introduced to North America by European settlers. They’re a hardy, dual purpose breed sometimes raised for meat or for milk, and they aren’t picky about what they eat.

“Often with newer breeds, people are trying to breed them back towards eating grass instead of grain,” he explains. “But Devons have always thrived on grass. And as a history teacher, having a breed used here back in the 1600s means a lot to me.”

After the cattle, chickens follow in mobile coops. “Chickens are omnivores, eating grass, bugs and grubs and turning that into a source of fertility with their manure,” says Holladay. “We use them to target areas that need more fertility while creating a delicious product for us to sell.”

Sheep have recently joined the grazing rotation too, creating yet another source of income from their fields. They’ve been careful to only introduce animals whose eating habits compliment the other species and don’t cut into their haying revenue. Yet from a business standpoint, offering more variety is good for them and their customers, since fans of local grass-fed beef are often interested in other pasture-raised meat too. As Cowley puts it, after enjoying meat raised this way, it’s hard to compare with meat raised other ways.

“From my experience, raising animals on pasture really affects the quality and taste of the meat,” he says. “Grass-fed beef cattle are raised longer than those in a feedlot, which means better marbling and richer color. And our beef is also vacuum-sealed and frozen immediately after it’s butchered, which is great for quality and convenience.”

Cuts of lamb are available now in addition to beef, and whole chickens will be available again later this summer. And as Holladay points out, “because we’re a small farm, we can really customize orders to exactly what people want. We can sell you the exact cut of lamb you want as the centerpiece for your fancy dinner party, or have your steaks cut a specific way.”

In the future, Cowley and Holladay hope to sell through local stores and farmers markets, but for now, all sales are straight from the farm. Pricing and availability are updated often on Gwydyr Farm’s Facebook page, and customers can contact them via the phone and email listed there.

Beef prices are set to encourage larger orders, including a guaranteed 20% off orders over $100 and an even bigger discount for buying over 10 pounds of ground beef.

Cowley and Holladay farm for a lot of reasons. On a day-to-day basis, they both love working with animals and seeing the tangible results of their work. On a deeper level, Cowley says Gwydyr Farm helps root him in this time and place, while recognizing the local history that precedes him.

“The way I farm, I’m not someone who buys all new equipment,” he says. “I love taking old farm equipment and making it work again. I love rehabilitating overgrown land and making it productive again. And I love restoring the connection between land, food and people.”

“The sense of community and meaning that comes from the Valley feeding itself are both valuable things,” he says. “We had a stronger sense of community and more local food in the past, and I think both are something we’re trying to get back to.”

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Mary Chicoine of Easthampton  Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night

Speaking of Nature: A romantic evening for two birders — To hear the wonderful sounds of the Saw-whet Owl one must go outside at night Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances

Speaking of Nature: Where have all the birds gone?: They’re there, and here’s a handy tool to keep track of their appearances Speaking of Nature: Who is that mysterious woodpecker?: Presence of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker in winter has caused quite a stir with readers

Speaking of Nature: Who is that mysterious woodpecker?: Presence of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker in winter has caused quite a stir with readers