Book Bag: ‘A Stranger in Baghdad’ by Elizabeth Loudon; ‘A Slant of Light’ by Ken Samonds

| Published: 06-09-2023 3:23 PM |

A Stranger in Baghdad

By Elizabeth Loudon; Hoopee/The American University in Cairo Press

British author Elizabeth Loudon, who once lived in the Valley, also lived for several months in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1975 to 1976 when she was in her late teens, a time she remembers vividly.

She made a number of Iraqi friends and was charmed by Baghdad’s souks and ancient mosques. But political tension and fear were rising, Loudon recalls, as the Ba’ath Party under Saddam Hussein cemented rigid control of the country.

Loudon, who later earned an MFA at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and taught at Smith and Amherst colleges, has revisited her experience in Iraq with her sweeping debut novel, “A Stranger in Baghdad,” a story that spans seven decades and examines modern Iraqi history from the viewpoint of an Iraqi-British family.

As such it offers a meditation on the impact of colonialism — Britain oversaw a good part of Iraqi life for decades after the country was carved out of the former Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I — and how British-Iraqi conflicts play out within the ranks of a mixed family.

Told alternately from the standpoint of Mona Haddad, an Iraqi-British psychiatrist, and her English mother, Diane, “A Stranger in Baghdad” begins with a short section set in London in 2003, after the U.S. has invaded Iraq in its quest to depose Saddam Hussein.

Mona, who’s 50, gets an unexpected visit from an aged former British diplomat, Duncan Claybourne, who had known Diane as a young woman in Baghdad in the late 1930s. He has a confession to make, one that will shed some light both on a mysterious event from Diane’ s past and other aspects of Mona’s family history.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

‘Knitting treasure’ of the Valley: Northampton Wools owner spreads passion for ancient pastime

‘Knitting treasure’ of the Valley: Northampton Wools owner spreads passion for ancient pastime

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

South Hadley Town Meeting OK’s budget that lays off 24 school staff; nuisance bylaw tabled

South Hadley Town Meeting OK’s budget that lays off 24 school staff; nuisance bylaw tabled

Host of road projects to begin Friday in Amherst

Host of road projects to begin Friday in Amherst

That’s the cue for the novel to pivot to the late 1930s, when Diane, a young nurse whose unconventional views exasperate her parents and older sister, impulsively marries an older Iraqi doctor, Ibrahim, who’s studying in London, and then moves with him to Baghdad.

Culture shock may be a cliché, but Diane certainly experiences it as she deals with blazing temperatures, her lack of Arabic, and the initially cool reception she gets from Ibrahim’s mother and sisters, who wonder what he sees in this Englishwoman, beyond her good looks.

Yet Diane eventually begins to find her way, learning Arabic and developing a better relationship with one of her sisters-in-law, Laila, who had previously lived in England. She also gets a job, through the British embassy, as a nanny of Faisal, the young son of Iraq’s monarch, King Ghazi, though Ibrahim is not pleased that his wife is working outside the home.

Tensions flare when Ghazi suddenly dies, reportedly in a car crash, though many Iraqis are convinced he’s been murdered, perhaps with British cooperation. Even Diane’s Iraqi family looks suspiciously at her, wondering if she’s somehow involved.

These Iraqi-British conflicts will only increase in the ensuing decades, as the country is wracked by a number of military coups, including the assassination of Diane’s former charge, King Faisal II, Iraq’s last monarch, killed in 1958 at age 23.

Mona, one of three children of Diane and Ibrahim – Mona has an older and younger brother – takes over the novel’s narration at this point, lending a new twist to the story as she clashes with her mother and tries to win more approval from her father, at a time when there’s growing hostility in Iraq to westerners.

The family’s mixed Anglo-Iraqi status brings them increased scrutiny from the government. “For the first time ever, our letters from England are censored,” Mona relates. “They make no effort to hide the censorship. If anything they are mocking us. They tear envelopes open and and black out whole lines at random.”

The family’s phone line is tapped, and paranoia increases: “We suspect everybody now. The garden boy who comes once a week lingers too long on our porch … The parafin seller … stares in a strange way at our house.”

The dangers the family faces are real, and the story turns into something of a page turner as the Iraqi security state steps up its scrutiny in the 1970s and upends the family’s life, bringing some tragic losses.

But in press notes, Loudon, a former college lecturer in England who has also published short fiction and poetry, says her goal with the book has been to show a deeper side of Iraqi culture, one extending beyond the stereotypes westerners have gleaned from news coverage of the 1991 and 2003 U.S.-Iraq wars, while acknowledging the problems Iraq has had under dictatorial rule.

Reflecting on her time in Iraq in 1975 and 1976, she says, “I wanted to share the spirit of hospitality and friendship that I felt so strongly amongst my friends … (and) I wondered how I might tell a story that brought Iraqis and westerners together, a story that presented believable people with whom we could all empathise.”

“A Stranger in Baghdad” also examines issues specific to women, such as young marriage, miscarriages, sisterhood, and Mona’s struggle to please her father; Loudon says all these themes are critical parts of the narrative.

“I’m interested … in how our perspectives illuminate each other. Different cultures challenge me to explore or change my own beliefs about my experiences as a woman.”

Elizabeth Loudon will read from and discuss “A Stranger in Baghdad” June 14 at 7 p.m. at Broadside Bookshop in Northampton.

A Slant of Light: The Stained Glass Windows of Grace Church

By Ken Samonds

Combray House Books

William Gibson may not be a household name in U.S. history, but the 19th-century craftsman is generally regarded as having established the first stained-glass business in the United States.

In fact, the Scottish immigrant, who worked in New York City, called himself the “Father of American Stained Glass” in some of his advertisements.

Today, little of Gibson’s work survives. But it can still be seen at Grace Church in Amherst, and in his book “A Slant of Light,” Ken Samonds, a former University of Massachusetts Amherst professor, examines the history behind the work.

Samonds, who became an unofficial historian of Grace Church over the years, has researched the story behind its historic windows, 20 of which were installed in 1865. His richly illustrated book also digs into Gibson’s background and the technologies he used in making his windows.

Samonds notes that many U.S. churches updated their windows in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, adding new styles – but not Grace Church.

In addition, the windows are unusual in that several of them commemorate the lives of local residents, using unconventional symbols rather than traditional Christian iconography. One of those people was Susan Davis Phelps of Hadley, a friend of Emily Dickinson.

Oh, and the title of Samonds’ book? It’s from a Dickinson poem, of course.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia

Connected through art: Rocky Hill Cohousing community participates in art exchange with group from Australia Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets

Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season

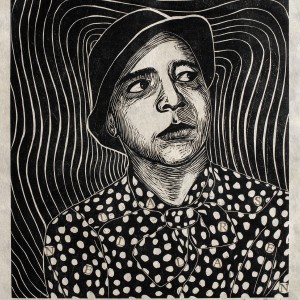

Get Growing with Mickey Rathbun: Venture beyond your garden walls: Plant sales and noteworthy gardens to visit this season Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past

Overlooked no more: Leverett artist’s woodcut prints celebrate remarkable women of the past