Latest News

Donating hope: Survivors share stories at Northampton event as part of Organ Donation Month

NORTHAMPTON — The day before Thanksgiving in 2016, Northampton resident Bob Wood got a life-changing call — literally. A 42-year-old woman in Pennsylvania had recently died, and her liver would be a perfect fit for Wood, now 68 years old, who...

Amherst poised to hire police department veteran as new chief

AMHERST — Temporary Police Chief Gabriel Ting, who has led the department since last May and been a member of the force for almost 27 years, will become Amherst’s permanent chief, pending approval by the Town Council.Ting’s appointment to serve a...

Sports

Girls lacrosse: Anna Puttick helps Hampshire take down Granby 13-9 (PHOTOS)

GRANBY – Anna Puttick won the draw, sprinted downfield, weaved between a few Granby defenders and then scored to give Hampshire Regional a 6-4 lead on the opening possession of the second half.Then, about 20 seconds later, the Raiders senior captain...

Boys lacrosse: Jack Carpenter, Northampton hold off Belchertown for 7-6 win

Boys lacrosse: Jack Carpenter, Northampton hold off Belchertown for 7-6 win

Mount Holyoke names Abby Wemhoff as new head basketball coach

Mount Holyoke names Abby Wemhoff as new head basketball coach

Opinion

Guest columnist Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

I continue to be consumed by the Israel-Hamas war. I read, watch, write, pray, dream, agonize, and do my best to engage in intentional and nuanced conversations about it. And yet there remain things I have not said.Or things I have said by...

Wendy Parrish: Northampton Volunteer Fair

Wendy Parrish: Northampton Volunteer Fair

Guest columnist Oriel Strong: Think impossible thoughts

Guest columnist Oriel Strong: Think impossible thoughts

Business

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

NORTHAMPTON — A joint meeting between the Northampton City Council’s Committee on Legislative Matters and the city’s Planning Board heard public comments on a petition to ban further automobile dealerships near the city’s downtown, an issue that...

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

During a recent lecture on evolutioin I had to explain the differences between three different processes known as geographic, temporal and behavioral isolation. Geographic isolation is the easiest of these concepts to understand because it involves...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Charles W. Curtin

Charles W. Curtin

Northampton, MA - Charles W. Curtin, 96, passed away peacefully on April 19, 2024 at Cooley Dickinson Hospital in Northampton, MA. Born on November 1, 1927 to the late William and Gertrude (Duffey) Curtin. He was raised in Florence, MA.... remainder of obit for Charles W. Curtin

Carol Butler Watelet

Carol Butler Watelet

Greenfield, MA - Carol (Virginia) Soucie Butler Watelet, 85, passed away suddenly and peacefully on April 20, 2024, joining the love of her life, Mr. Wonderful, Robert Watelet who passed away 2 years earlier. Carol was born on March 17,... remainder of obit for Carol Butler Watelet

Maryann Burke

Maryann Burke

Hatfield, MA - Maryann Burke (DeMatto), beloved wife, mother and Nonna, passed away on April 19, 2024, with her loving husband by her side. Maryann was born in Holyoke, MA on September 3, 1944, to the late Joseph and Emelia DeMatto. ... remainder of obit for Maryann Burke

Guest columnist Rob Okun: Still No. 1 in male mass shootings 25 years after Columbine

Guest columnist Rob Okun: Still No. 1 in male mass shootings 25 years after Columbine

Contentious dispute ends as Hampshire Regional schools, union settle on contract

Contentious dispute ends as Hampshire Regional schools, union settle on contract

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

Shutesbury TM on Saturday will rule on battery storage, lighting bylaws, citizen petitions and hold elections

Shutesbury TM on Saturday will rule on battery storage, lighting bylaws, citizen petitions and hold elections

Amherst regional district towns seek middle ground on school increase

Amherst regional district towns seek middle ground on school increase

Prescription drug take back day set for Saturday in 15 communities in Hampshire, Franklin counties

Prescription drug take back day set for Saturday in 15 communities in Hampshire, Franklin counties

Area briefs: Suicide prevention forum; ‘American Symphony’ screening; Zonta grant awards

Area briefs: Suicide prevention forum; ‘American Symphony’ screening; Zonta grant awards

Senate may reform trio of consumer laws: competitive electricity, used car sales, heating oil leaks

Senate may reform trio of consumer laws: competitive electricity, used car sales, heating oil leaks

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

A Look Back, April 24

A Look Back, April 24 Photos: Hangers for history

Photos: Hangers for history Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more 2024 Gazette Boys Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Nicolas Lisle, Amherst

2024 Gazette Boys Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Nicolas Lisle, Amherst Baseball: Northampton nearly comes all the way back before falling to Chicopee 15-14 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Northampton nearly comes all the way back before falling to Chicopee 15-14 (PHOTOS) Guest columnist Barry Hirsch: Palestinians should turn to Israel for real path to peace

Guest columnist Barry Hirsch: Palestinians should turn to Israel for real path to peace Patricia Crosby: Meeting of Friends call for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza

Patricia Crosby: Meeting of Friends call for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28 Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

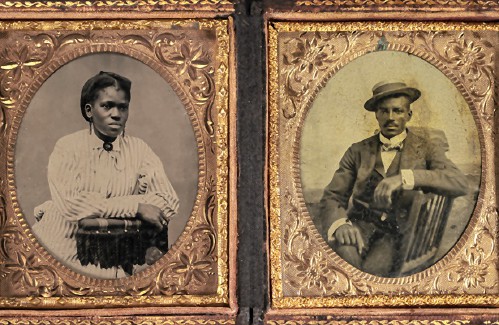

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near