Latest News

LightHouse Holyoke to buy Gateway City Arts, expand offerings and enrollment at alternative school

HOLYOKE — After months of work on securing a new home elsewhere, LightHouse school plans to buy Gateway City Arts in a move that will allow the burgeoning alternative secondary school to meet its growing demand and expand its offerings.LightHouse...

Neighbors lifting neighbors: Demand at South Hadley’s food bank spiking as more families seek help

SOUTH HADLEY — Never go hungry.It’s the one rule that must not be broken at Neighbors Helping Neighbors, the organization that over the last 14 years has helped thousands of people from South Hadley and surrounding towns keep food on the table during...

Sports

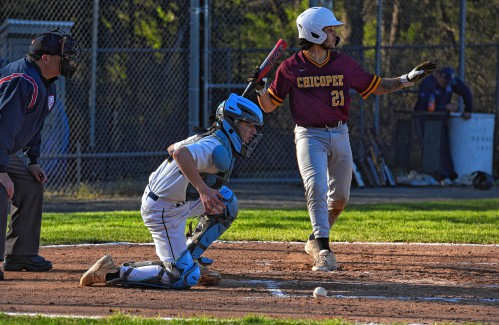

Baseball: Northampton nearly comes all the way back before falling to Chicopee 15-14 (PHOTOS)

NORTHAMPTON — It looked like a comeback that would be talked about for years to come for the Northampton baseball team.Behind 14-5 entering the bottom of the sixth inning on their home field, the Blue Devils refused to roll over in the late stages of...

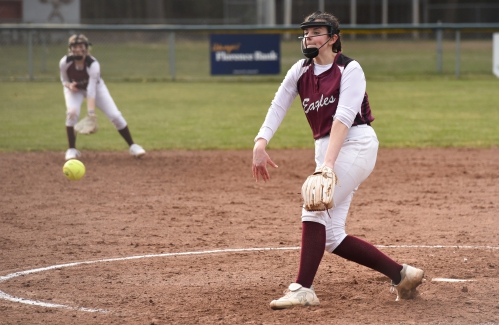

High schools: Rosie Follet, Easthampton shut down Agawam in 3-1 win

High schools: Rosie Follet, Easthampton shut down Agawam in 3-1 win

Opinion

Guest columnist Oriel Strong: Think impossible thoughts

Mariel E. Addis’s April 17 guest column “Under siege from all sides” was heartfelt and thought-provoking. I share Addis’ foundational ethic that we must resist ranking any human being as better or worse than another. Trans and gender-nonconforming...

Guest columnist Barry Hirsch: Palestinians should turn to Israel for real path to peace

Guest columnist Barry Hirsch: Palestinians should turn to Israel for real path to peace

Patricia Crosby: Meeting of Friends call for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza

Patricia Crosby: Meeting of Friends call for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza

Columnist Richard Fein: National debt — A threat to our nation’s future

Columnist Richard Fein: National debt — A threat to our nation’s future

My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights

My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights

Business

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

NORTHAMPTON — A joint meeting between the Northampton City Council’s Committee on Legislative Matters and the city’s Planning Board heard public comments on a petition to ban further automobile dealerships near the city’s downtown, an issue that...

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Arts & Life

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

A lot can change in 20 years: Presidents and other politicians come and go, new cultural fads and technologies emerge, clothing styles morph, and music and movies take on different dimensions.In these parts, one tradition hasn’t changed. Since 2005,...

Obituaries

Maryann Burke

Maryann Burke

Hatfield, MA - Maryann Burke (DeMatto), beloved wife, mother and Nonna, passed away on April 19, 2024, with her loving husband by her side. Maryann was born in Holyoke, MA on September 3, 1944, to the late Joseph and Emelia DeMatto. ... remainder of obit for Maryann Burke

Crystal L. Bergeron

Crystal L. Bergeron

Crystal L Bergeron Easthampton, MA - Crystal L Bergeron, 39, of Easthampton sadly left us as she passed away peacefully at home on April 11th, 2024. She was born July 18, 1984, to Roger J Bergeron and Darlene J Bergeron. Crystal had the ... remainder of obit for Crystal L. Bergeron

Richard A. Weber

Richard A. Weber

Richard A Weber Shutesbury, MA - In the earliest hour of Saturday, April 13, 2024, surrounded by the tremendous love of his family, Richard Weber, 60, gently left this world. Rich leaves behind an amazing group of folks who loved him wh... remainder of obit for Richard A. Weber

Daniel James Moriarty

Daniel James Moriarty

Granby, MA - Daniel J. Moriarty, 66, passed away unexpectedly on April 14, 2024. He was born January 12, 1958 in Holyoke, MA. to the late Donald and Marie Moriary. Daniel grew up in South Hadley and graduated from South Hadley High Scho... remainder of obit for Daniel James Moriarty

Senate may reform trio of consumer laws: competitive electricity, used car sales, heating oil leaks

Senate may reform trio of consumer laws: competitive electricity, used car sales, heating oil leaks

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

Granby man admits guilt, gets 2½ years in vehicular homicide

South Hadley residents will pay more for trash, wastewater rates next fiscal year

South Hadley residents will pay more for trash, wastewater rates next fiscal year

Area briefs: Transhealth to celebrate 3 year; Holyoke to plant tree at museum; Documentary film about reparations focus of Unitarian talk

Area briefs: Transhealth to celebrate 3 year; Holyoke to plant tree at museum; Documentary film about reparations focus of Unitarian talk

Leverett Town Meeting voters will decide cease-fire call, budgets, town elections

Leverett Town Meeting voters will decide cease-fire call, budgets, town elections

UMass set to inaugurate Javier Reyes as chancellor on Friday

UMass set to inaugurate Javier Reyes as chancellor on Friday

Amherst seeks public input on opioid settlement money

Amherst seeks public input on opioid settlement money

Deerfield residents petitioning to fix ‘dangerous’ intersection

Deerfield residents petitioning to fix ‘dangerous’ intersection

Amherst officials examine Quincy shelter for ideas to develop former VFW property

Amherst officials examine Quincy shelter for ideas to develop former VFW property

A Look Back: April 23

A Look Back: April 23 Photos: Hangers for history

Photos: Hangers for history Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more Softball: Offense erupts as Hampshire Regional thumps East Longmeadow 15-3 to get back in win column

Softball: Offense erupts as Hampshire Regional thumps East Longmeadow 15-3 to get back in win column Owen Dawson notches 200th career point for South Hadley boys lacrosse team

Owen Dawson notches 200th career point for South Hadley boys lacrosse team South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College

South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

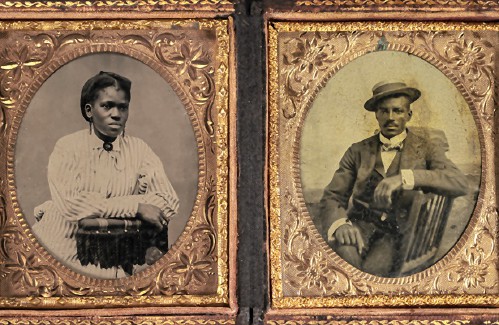

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here