Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

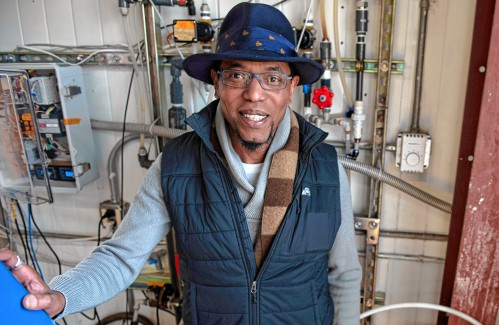

HOLYOKE — Like many people, Michael Garjian believes global warming is a pressing issue of our times.Unlike most, he’s putting his ideas for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into practice — and at the same time bidding for a share of the...

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

AMHERST — In the four years since its founding on the UMass campus, startup Elateq Inc., a water treatment and hardware company, has landed contracts big (think PepsiCo) and small (think town of Amherst).Now the company, which uses advanced...

Sports

High schools: Northampton boys tennis takes down Amherst in rain-shortened title-game rematch (PHOTOS)

AMHERST – Amherst’s Miles Jeffries took the first set from Northampton’s Reilly Fowles on Wednesday afternoon, but rain shortened what had the potential to be the best boys tennis match of the season in Hampshire County. Amherst coach Kevin Jeffries...

High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby

High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby

Local briefs: Amherst Youth Baseball, Northampton Youth Softball

Local briefs: Amherst Youth Baseball, Northampton Youth Softball

Girls lacrosse: Anna Puttick helps Hampshire take down Granby 13-9 (PHOTOS)

Girls lacrosse: Anna Puttick helps Hampshire take down Granby 13-9 (PHOTOS)

Opinion

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Vacancies at programs operated by human services providers — despite some progress over the last two years — are still much too high. More than one in four direct support professional positions in adult residential and day programs for people with...

Lora Sandhusen: Discourage ultra-wealthy consumption habits with carbon tax

Lora Sandhusen: Discourage ultra-wealthy consumption habits with carbon tax

Guest columnist Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Guest columnist Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Wendy Parrish: Northampton Volunteer Fair

Wendy Parrish: Northampton Volunteer Fair

Business

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

NORTHAMPTON — A joint meeting between the Northampton City Council’s Committee on Legislative Matters and the city’s Planning Board heard public comments on a petition to ban further automobile dealerships near the city’s downtown, an issue that...

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

During a recent lecture on evolutioin I had to explain the differences between three different processes known as geographic, temporal and behavioral isolation. Geographic isolation is the easiest of these concepts to understand because it involves...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Donald E. Hooton

Donald E. Hooton

South Hadley, MA - South Hadley Donald E. Hooton, 91, passed away peacefully on Sunday, April 21 st , 2024, surrounded by his loving family. He was born in Holyoke to the late Eva (Utley) and Leonard Hooton. Donald moved to South ... remainder of obit for Donald E. Hooton

Peter G. Tobin

Peter G. Tobin

Leeds, MA - Peter G. Tobin, 59, of Evergreen Rd. in Leeds passed away peacefully at his home on Tuesday, with his daughter Meghan and his former wife, Cathy Tobin at his side. Peter leaves his devoted daughter Meghan and his beloved cat... remainder of obit for Peter G. Tobin

Doris Ilnicky

Doris Ilnicky

S. Hadley, MA - Doris M. Ilnicky, 76, of S. Hadley, passed away peacefully on Friday, April 12, 2024, with her daughter, son in law, and niece by her side. She was born February 26, 1948, in Northampton to the late Octave and Alice (Bai... remainder of obit for Doris Ilnicky

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

William Strickland, a longtime civil rights activist, scholar and friend of Malcolm X, has died

William Strickland, a longtime civil rights activist, scholar and friend of Malcolm X, has died

Northampton City Briefing: Council adjust start time for its meetings; Farmer’s Market to begin 49th year on Saturday; CDH blood drive coming up

Northampton City Briefing: Council adjust start time for its meetings; Farmer’s Market to begin 49th year on Saturday; CDH blood drive coming up

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Report tallies pros of energy retrofit at Hopkins Academy

Report tallies pros of energy retrofit at Hopkins Academy

Belchertown mobile home village getting new water system

Belchertown mobile home village getting new water system

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

A Look Back, April 25

A Look Back, April 25 Photos: Plaque of remembrance

Photos: Plaque of remembrance Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more 2024 Gazette Girls Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Allie Sullivan, Northampton

2024 Gazette Girls Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Allie Sullivan, Northampton Guest columnist Rob Okun: Still No. 1 in male mass shootings 25 years after Columbine

Guest columnist Rob Okun: Still No. 1 in male mass shootings 25 years after Columbine Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28 Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

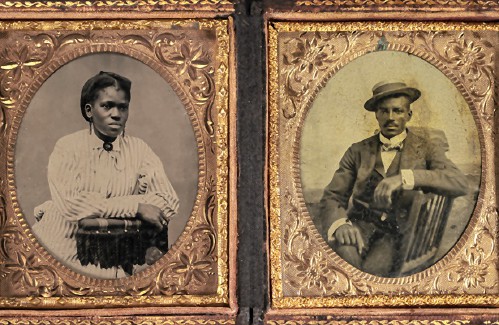

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near