Latest News

Holyoke man finds bear paw in his yard

Holyoke man finds bear paw in his yard

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

NORTHAMPTON — A joint meeting between the Northampton City Council’s Committee on Legislative Matters and the city’s Planning Board heard public comments on a petition to ban further automobile dealerships near the city’s downtown, an issue that...

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

AMHERST — From their own journeys in Europe and across New England and the Northeast, and their experience in the hospitality industry, a Northampton couple is creating a market featuring wines, pantry staples and fresh, local produce in downtown...

Sports

High schools: Offense on fire for Granby girls lacrosse in 20-2 win over McCann Tech

Fourteen first-half goals helped the Granby girls lacrosse team to a dominant 20-2 victory over McCann Tech on Wednesday afternoon.Eleven different players recorded goals in the win.Brenna Moreno’s four goals and Kalli White’s hat trick led the way...

Baseball: Chicopee Comp strikes early, takes down Amherst (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Chicopee Comp strikes early, takes down Amherst (PHOTOS)

Florence’s Gabby Thomas gearing up for 2024 Paris Olympics

Florence’s Gabby Thomas gearing up for 2024 Paris Olympics

Jiri Smejkal gets 1st goal, Senators beat Bruins 3-1 in regular-season finale

Jiri Smejkal gets 1st goal, Senators beat Bruins 3-1 in regular-season finale

High schools: Belchertown, Easthampton split dual track meet (PHOTOS)

High schools: Belchertown, Easthampton split dual track meet (PHOTOS)

Opinion

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Under seige from all sides

When I first heard John Lennon’s masterpiece “Imagine,” and heard the line “imagine no religion,” I thought, “How awful is that; religion is a good thing!” Probably in junior high at the time, I couldn’t understand the significance of the line. I do...

Julia Riseman: Join Friends of Northampton Trails

Julia Riseman: Join Friends of Northampton Trails

Shelly Berkowitz: More examples of corporate greed

Shelly Berkowitz: More examples of corporate greed

Rachel Vigderman: Area women ending silence over weaponization of rape

Rachel Vigderman: Area women ending silence over weaponization of rape

Business

Area property deed transfers, April 18

AMHERST 44 Chapel Rd, $560,750, B: Kristin M. Flewelling and Christine L. Larson, S: Paul A. Schroeder and Maria Monasterios BELCHERTOWN 203 South St, $507,150, B: Glenna J. Young, S: M & F Land Dev LLC 45 West St, $200,000, B: Serenity Ft and...

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

I have just about reached the end of my patience with the winter of 2024. I realize that this may sound a bit strange, especially because we are now in the beginning of spring, but those of us who bore the brunt of the April snowstorm may sympathize...

Obituaries

Garry Tudryn

Garry Tudryn

[IMAGE]GARRY TUDRYN HATFIELD, MA - Garry Morrison Tudryn, 67 of West Street in Hatfield, passed away April 13, 2024 at the Care One Nursing and Rehab Center in Northampton. Born in Northampt... remainder of obit for Garry Tudryn

Jacques Ben Abbes

Jacques Ben Abbes

HADLEY, MA - Jacques Ben Abbes, leaves his wife, Ngoc Anh Tran. Children; Vincent Tran (Nhu Nguyen) and Jacqueline Ben Abbes (Victor Loye) Grandchildren, Benjamin and Scott Tran. CALLIN... remainder of obit for Jacques Ben Abbes

Geraldine Packard

Geraldine Packard

Northampton, MA - Geraldine Packard, 87, passed away at her home in Northampton on April 13, 2024. Born to Curtis and Mildred (Smith) Chase on September 23, 1936 in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire... remainder of obit for Geraldine Packard

Russell E. Lent Sr.

Russell E. Lent Sr.

[IMAGE]Russell E. Lent, Sr. Easthampton, MA - Russell Eugene Lent, Sr. 89, longtime resident of Easthampton, passed away peacefully on Friday April 12, 2024, at his home. Born in Coshocton, ... remainder of obit for Russell E. Lent Sr.

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Amherst Fire Chief Walter ‘Tim’ Nelson to retire in June

Amherst Fire Chief Walter ‘Tim’ Nelson to retire in June

First look at how little Amherst’s police alternative being used called troubling

First look at how little Amherst’s police alternative being used called troubling

Developer pitches new commercial building on Route 9 in Hadley

Developer pitches new commercial building on Route 9 in Hadley

Mass. saw nearly 200 percent rise in antisemitic incidents last year

Mass. saw nearly 200 percent rise in antisemitic incidents last year

Three finalists named for Ryan Road School principal in Northampton

Three finalists named for Ryan Road School principal in Northampton

Guest columnist Jim Palermo: Beware the zeitgeist! It’s bad for our kids

Guest columnist Jim Palermo: Beware the zeitgeist! It’s bad for our kids

A Look Back: April 17

A Look Back: April 17 Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries

Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries  News Briefs: Roadwork in Plainfield; bake sale in Hadley

News Briefs: Roadwork in Plainfield; bake sale in Hadley LIME SPREADER

LIME SPREADER Justine McCarthy and Ed Lamoureux: Political will needed to benefit from new power line technology

Justine McCarthy and Ed Lamoureux: Political will needed to benefit from new power line technology Recognizing an ‘inspiring force’: City business owner honored with Black Excellence award

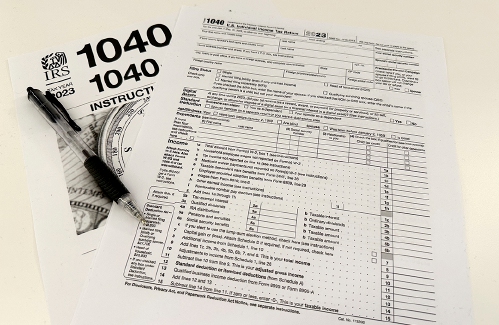

Recognizing an ‘inspiring force’: City business owner honored with Black Excellence award Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips

Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke

Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton

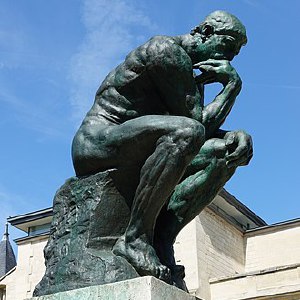

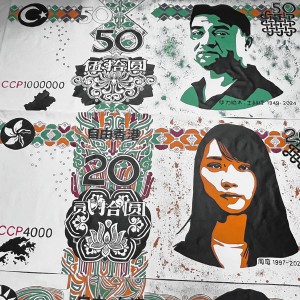

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation

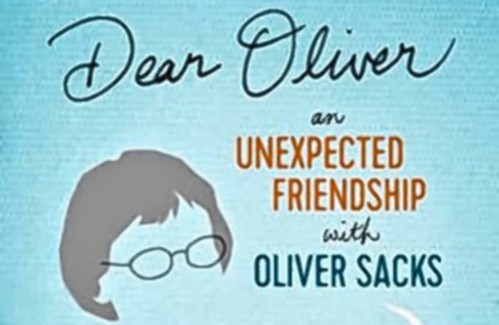

What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin

Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back

Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back