Latest News

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

SUNDERLAND — Police located a cabin in the woods around Clark Mountain Road Thursday afternoon believed to belong to Taaniel Herberger-Brown, the suspect accused of murdering a man at 92 Chapman St. and storing his body in a plastic barrel for an...

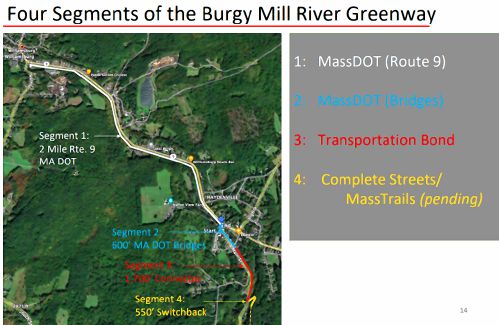

Haydenville residents resist Greenway trail plan, float alternative design

WILLIAMSBURG — With decision time nearing on the first section of the long-planned Mill River Greenway that will one day create a trail connection from Northampton to Williamsburg, a dispute over the project’s design through Haydenville’s residential...

Most Read

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

Treehouse, Big Brothers Big Sisters turn race schedule snafu into positive

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Northampton man will go to trial on first-degree murder charge after plea agreement talks break down

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Contentious dispute ends as Hampshire Regional schools, union settle on contract

Contentious dispute ends as Hampshire Regional schools, union settle on contract

South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College

South Hadley’s Lauren Marjanski signs National Letter of Intent to play soccer at Siena College

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Editors Picks

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more

Arts Briefs: A themed exhibit in Northampton, new opportunities for artists in Easthampton, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

2024 Gazette Ice Hockey Player of the Year: Cooper Beckwith, Amherst

It was the beginning of the 2021-22 hockey season, and Amherst captain Carter Beckwith and assistant captain Nick Paul were tasked with finding a second assistant captain to round out the group.It didn’t take long for the pair of seniors to come to a...

High schools: Northampton boys tennis takes down Amherst in rain-shortened title-game rematch (PHOTOS)

High schools: Northampton boys tennis takes down Amherst in rain-shortened title-game rematch (PHOTOS)

High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby

High schools: South Hadley baseball shakes off slow start, runs past Granby

Local briefs: Amherst Youth Baseball, Northampton Youth Softball

Local briefs: Amherst Youth Baseball, Northampton Youth Softball

Opinion

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution pins ‘aggression’ on Iran

Both the Iranian government’s bombing of Israel and the Israeli government’s bombing of Iran are extremely perilous for the Middle East and the United States. That is why the dangerously one-sided U.S. congressional resolution, H.Res. 1143,...

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

David Kirk: Northampton schools spending beyond means

Richard Clifford: We all need to look in a mirror first

Richard Clifford: We all need to look in a mirror first

Business

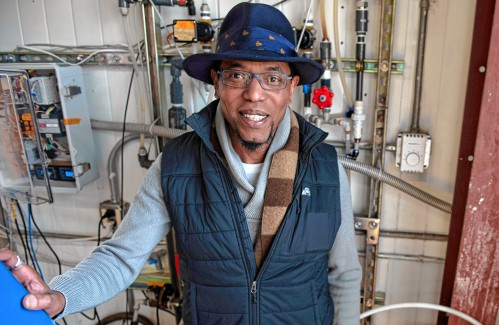

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

HOLYOKE — Like many people, Michael Garjian believes global warming is a pressing issue of our times.Unlike most, he’s putting his ideas for reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into practice — and at the same time bidding for a share of the $100...

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Area property deed transfers, April 25

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

Upon Nancy’s Floor: 33 Hawley event celebrates iconic dancers, history, and a new dance floor

Among the many features that are part of 33 Hawley, the Northampton Community Arts Trust building that was finally completed in early January following 10 years of construction, there’s probably nothing more important to dancers than the floor of the...

Obituaries

Eli Knapp Abrams

Eli Knapp Abrams

Florence, MA - Eli Knapp Abrams, of Florence Massachusetts, passed away suddenly on Monday, April 22nd, 2024 in Goshen, MA. Eli was born in Beverly, MA on March 19th, 2003. He is the cherished son of Jennifer and Maury Abrams, and belov... remainder of obit for Eli Knapp Abrams

Donald E. Hooton

Donald E. Hooton

South Hadley, MA - South Hadley Donald E. Hooton, 91, passed away peacefully on Sunday, April 21 st , 2024, surrounded by his loving family. He was born in Holyoke to the late Eva (Utley) and Leonard Hooton. Donald moved to South ... remainder of obit for Donald E. Hooton

Peter G. Tobin

Peter G. Tobin

Leeds, MA - Peter G. Tobin, 59, of Evergreen Rd. in Leeds passed away peacefully at his home on Tuesday, with his daughter Meghan and his former wife, Cathy Tobin at his side. Peter leaves his devoted daughter Meghan and his beloved cat... remainder of obit for Peter G. Tobin

Doris Ilnicky

Doris Ilnicky

S. Hadley, MA - Doris M. Ilnicky, 76, of S. Hadley, passed away peacefully on Friday, April 12, 2024, with her daughter, son in law, and niece by her side. She was born February 26, 1948, in Northampton to the late Octave and Alice (Bai... remainder of obit for Doris Ilnicky

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Columnist Susan Wozniak: Rising costs long ago swamped hippie ideal

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

Supreme Court seems skeptical of Trump’s claim of absolute immunity but decision's timing is unclear

Supreme Court seems skeptical of Trump’s claim of absolute immunity but decision's timing is unclear

Hatfield eyes reserves to cover unexpected spike in payments to Smith Vocational

Hatfield eyes reserves to cover unexpected spike in payments to Smith Vocational

Ashfield considers seeking ‘Climate Leader’ designation

Ashfield considers seeking ‘Climate Leader’ designation

Building conversion, battery storage bylaws up for vote at Sunderland Town Meeting

Building conversion, battery storage bylaws up for vote at Sunderland Town Meeting

Area briefs: Bonifaz to speak at Law Day events; Easthampton Film Festival preps for third year; Granby Candidates Night

Area briefs: Bonifaz to speak at Law Day events; Easthampton Film Festival preps for third year; Granby Candidates Night

More arrested in pro-Palestinian campus protests ahead of college graduation ceremonies

More arrested in pro-Palestinian campus protests ahead of college graduation ceremonies

2024 Gazette Girls Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Allie Sullivan, Northampton

2024 Gazette Girls Indoor Track Athlete of the Year: Allie Sullivan, Northampton Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

Columnist Carrie N. Baker: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28 Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many