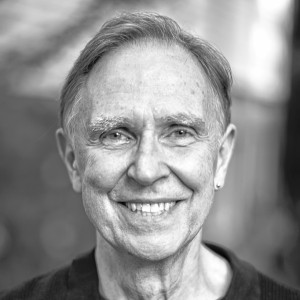

New HCC president reflects on journey: Timmons sees his own struggles and arc in students’ paths

HOLYOKE — George Timmons knows just how much a difference a college president can make in a student’s life.As a senior at Norfolk State University, a historically black university in Virginia, Timmons faced the possibility of not being able to...

Boards balk at limiting use of Hadley Town Common

HADLEY — Significant work and time for municipal staff associated with preparing for New England Public Media’s annual Asparagus Festival is prompting Hadley officials to examine whether fees should be increased and other adjustments made to how...

Most Read

Holyoke man finds bear paw in his yard

Holyoke man finds bear paw in his yard

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

First look at how little Amherst’s police alternative being used called troubling

First look at how little Amherst’s police alternative being used called troubling

Developer lands $400K loan for affordable housing project in Easthampton mill district

Developer lands $400K loan for affordable housing project in Easthampton mill district

Developer pitches new commercial building on Route 9 in Hadley

Developer pitches new commercial building on Route 9 in Hadley

Boyfriend accused in slaying of Hampden sheriff’s assistant, former legislator’s top aide

Boyfriend accused in slaying of Hampden sheriff’s assistant, former legislator’s top aide

Editors Picks

A Look Back: April 19

A Look Back: April 19

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

The Beat Goes On: Album release shows by Barnstar! and Lisa Bastoni, a Young@Heart Chorus concert with new special guests, and more

Sports

Southampton’s Hannah Wodecki breaks Westfield State softball’s single season RBI record

WESTFIELD — As cliche as it sounds, records are truly made to be broken.And Westfield State sophomore Hannah Wodecki didn’t just break an Owls softball record, she’s going to shatter it when all is said and done.With still 10 regular season games...

The Real Score: Curveballs and casinos rarely save cities

The Real Score: Curveballs and casinos rarely save cities

Opinion

Taylor Guss: Northampton's zoning should align with its climate goals

Humanity is currently facing the crisis of a generation with climate change. We exceeded 1.3 degrees Celsius of warming in 2023, just shy of 1.5 degrees, the threshold scientists warn could have catastrophic consequences for the planet. Northampton...

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Under seige from all sides

Guest columnist Mariel E. Addis: Under seige from all sides

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Julia Riseman: Join Friends of Northampton Trails

Julia Riseman: Join Friends of Northampton Trails

Business

Petition to block auto dealership on King Street falters in Northampton

NORTHAMPTON — A joint meeting between the Northampton City Council’s Committee on Legislative Matters and the city’s Planning Board heard public comments on a petition to ban further automobile dealerships near the city’s downtown, an issue that...

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Flair and flavor: Couple draws on European, regional travel and food expertise to bring gourmet Aster + Pine Market to Amherst

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Prices up, sales down in early spring housing market

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Area property deed transfers, April 18

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Arts & Life

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

A lot can change in 20 years: Presidents and other politicians come and go, new cultural fads and technologies emerge, clothing styles morph, and music and movies take on different dimensions.In these parts, one tradition hasn’t changed. Since 2005,...

Obituaries

Garry Tudryn

Garry Tudryn

[IMAGE]GARRY TUDRYN HATFIELD, MA - Garry Morrison Tudryn, 67 of West Street in Hatfield, passed away April 13, 2024 at the Care One Nursing and Rehab Center in Northampton. Born in Northampt... remainder of obit for Garry Tudryn

Jacques Ben Abbes

Jacques Ben Abbes

HADLEY, MA - Jacques Ben Abbes, leaves his wife, Ngoc Anh Tran. Children; Vincent Tran (Nhu Nguyen) and Jacqueline Ben Abbes (Victor Loye) Grandchildren, Benjamin and Scott Tran. CALLIN... remainder of obit for Jacques Ben Abbes

Geraldine Packard

Geraldine Packard

Northampton, MA - Geraldine Packard, 87, passed away at her home in Northampton on April 13, 2024. Born to Curtis and Mildred (Smith) Chase on September 23, 1936 in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire... remainder of obit for Geraldine Packard

Russell E. Lent Sr.

Russell E. Lent Sr.

[IMAGE]Russell E. Lent, Sr. Easthampton, MA - Russell Eugene Lent, Sr. 89, longtime resident of Easthampton, passed away peacefully on Friday April 12, 2024, at his home. Born in Coshocton, ... remainder of obit for Russell E. Lent Sr.

Columnist Andrea Ayvazian: Standing as witness to Armenian martyrs

Columnist Andrea Ayvazian: Standing as witness to Armenian martyrs

South Hadley man fatally shot in attempted robbery

South Hadley man fatally shot in attempted robbery

Historic murals restored at Victory Theatre in Holyoke

Historic murals restored at Victory Theatre in Holyoke

Guest columnist Bill Dwight: How to make sense of Northampton’s school budget dilemma

Guest columnist Bill Dwight: How to make sense of Northampton’s school budget dilemma

Holyoke man gets 5 years for assault, drug charges

Holyoke man gets 5 years for assault, drug charges

Shelter money fading, but ‘not at the end of the line’

Shelter money fading, but ‘not at the end of the line’

Columnist Russ Vernon-Jones: Climate solutions tough, but can be done

Columnist Russ Vernon-Jones: Climate solutions tough, but can be done

Sinkhole closes Eastman Lane in Amherst

Sinkhole closes Eastman Lane in Amherst

AT&T’s proposed cell tower extension moving forward in South Deerfield

AT&T’s proposed cell tower extension moving forward in South Deerfield

2018 World Series trophy to be in town for Sunday’s Northampton Baseball and Softball League opening day

2018 World Series trophy to be in town for Sunday’s Northampton Baseball and Softball League opening day Boys lacrosse: Landon Andre, Nico St. George help Belchertown hold off Amherst 11-9 (PHOTOS)

Boys lacrosse: Landon Andre, Nico St. George help Belchertown hold off Amherst 11-9 (PHOTOS) High schools: Offense on fire for Granby girls lacrosse in 20-2 win over McCann Tech

High schools: Offense on fire for Granby girls lacrosse in 20-2 win over McCann Tech Bridget Miller: Why walkability is the pathway to a healthy Amherst community

Bridget Miller: Why walkability is the pathway to a healthy Amherst community Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton