Three Amherst Regional Middle School counselors absolved of Title IX offenses

AMHERST — Even with complaints that their actions and behavior, including intentional misgendering students were likely offensive, three counselors at the Amherst Regional Middle School have been cleared of violations of the federal Title IX law in...

All about conviction: PVPA team wins state, heads to nationals of Mock Trial Championship

SOUTH HADLEY — Prepare, prepare, prepare.That’s the motto that mock trial coach Gary Huggert passes along to each new mock trial team at Pioneer Valley Performing Arts Charter School, a motto that took the team to the state finals for the past three...

Most Read

Next 5-story building cleared to rise in downtown Amherst

Next 5-story building cleared to rise in downtown Amherst

‘Our hearts were shattered’: Moved by their work in Mexico soup kitchen, Northampton couple takes action

‘Our hearts were shattered’: Moved by their work in Mexico soup kitchen, Northampton couple takes action

Hampshire County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Hampshire County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Amherst-Pelham schools look to address school absences with new plan

Amherst-Pelham schools look to address school absences with new plan

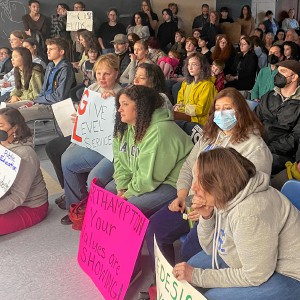

Northampton School Committee takes stand for budget increase during emotional meeting

Northampton School Committee takes stand for budget increase during emotional meeting

Amherst regional superintendent candidate stresses inclusion, broad expertise

Amherst regional superintendent candidate stresses inclusion, broad expertise

Editors Picks

Photos: Hearts and arts

Photos: Hearts and arts

Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries

Spring brings new art: A look at what's on tap in April at selected local galleries

Area briefs: Hadley cleanup; Mini golf in Holyoke; Dash and Dine race at UMass; HCC president inauguration

Area briefs: Hadley cleanup; Mini golf in Holyoke; Dash and Dine race at UMass; HCC president inauguration

Springfield man charged with murder in Holyoke stabbing

Springfield man charged with murder in Holyoke stabbing

Sports

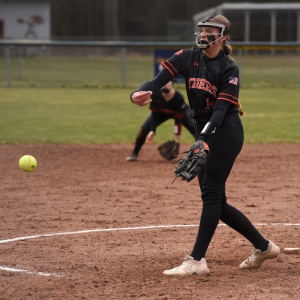

High school: Northampton softball slugs past Mahar for season's first victory (PHOTOS)

Following four frustrating losses to start the season, including three straight in five innings, the Northampton softball team was on the other side of a mercy-rule contest on Monday afternoon.The Blue Devils scored at least three runs in each of the...

Baseball: Smith Academy can't overcome early deficit in 13-6 loss to Mahar

Baseball: Smith Academy can't overcome early deficit in 13-6 loss to Mahar

Opinion

Guest columnist Jay Fleitman: Can’t leave Hamas intact

The editorial space of this newspaper is replete with demands for a cease-fire in Gaza, and similar demands have been made by the governing bodies of Northampton and Amherst. This really is a “demand” for the Israelis to unilaterally stop their...

Walter Krzeminski: Locals who homered at Fenway for the home team

Walter Krzeminski: Locals who homered at Fenway for the home team

Mary Collins: Let’s create 413 Day

Mary Collins: Let’s create 413 Day

Judy Gutlerner: More smiles

Judy Gutlerner: More smiles

Business

Recognizing an ‘inspiring force’: City business owner honored with Black Excellence award

NORTHAMPTON — A “good soul” and “inspiring force” who enriches western Massachusetts by bringing African culture to her new downtown store recently garnered some attention from the eastern part of the state.Aimee Salmon, the founder and operator of...

Black business group presses demand for Amherst relief funds

Black business group presses demand for Amherst relief funds

Black business association contests Amherst’s final $3.8M in ARPA spending

Black business association contests Amherst’s final $3.8M in ARPA spending

Arts & Life

Weekly Food Photo Contest: This week’s winner: Nicholas Horton of Northampton

This week’s winner, Nicholas Horton of Northampton, made Ethiopian food at home with his daughter Nari Horton (also of Northampton) “with injera provided by a daughter visiting from Minneapolis.”Submit pics at features@gazettenet.com.

Obituaries

Kathleen A. Dunn

Kathleen A. Dunn

Northampton, MA - Kathleen Ann (Spellman) Dunn, 79, of Northampton, MA, passed away on April 8, 2024 surrounded by family, at Community Hospice House in Merrimack, NH. She was born in P... remainder of obit for Kathleen A. Dunn

Joseph Walter Walas Jr.

Joseph Walter Walas Jr.

Joseph Walter Walas, Jr. East Haddam, CT - Joseph Walter Walas, Jr., 73, of East Haddam, formerly of Durham, and husband of the late Linda (Good) Walas, passed away on Wednesday, March 27, 2... remainder of obit for Joseph Walter Walas Jr.

Rose C. Trojanowski

Rose C. Trojanowski

Northampton, MA - Rose C. Trojanowski, 103, of Agawam, formerly of Northampton, passed away on Thursday, April 11, 2024, at Agawam North Nursing Home. She was born in Chicopee Falls on Janu... remainder of obit for Rose C. Trojanowski

Raymond P. Drewitz

Raymond P. Drewitz

Greenfield, MA - Raymond Drewitz, 40, of Greenfield, MA passed away peacefully with his wife and family by his side on April 10th 2024 at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, MA. Ray gre... remainder of obit for Raymond P. Drewitz

Hadley’s Brad Mish, Northampton’s Elianna Shwayder top Hampshire County finishers at 128th Boston Marathon

Hadley’s Brad Mish, Northampton’s Elianna Shwayder top Hampshire County finishers at 128th Boston Marathon

Softball: South Hadley’s Ella Schaeffer records 500th career strikeout in loss to East Longmeadow

Softball: South Hadley’s Ella Schaeffer records 500th career strikeout in loss to East Longmeadow

Two men dump milk, orange juice over themselves at Amherst convenience store

Two men dump milk, orange juice over themselves at Amherst convenience store

Columnist Razvan Sibii: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

Columnist Razvan Sibii: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

Lawmakers, Jewish groups accuse Massachusetts Teachers Association of bias

Lawmakers, Jewish groups accuse Massachusetts Teachers Association of bias

Homeless man gets three years for Northampton rape

Homeless man gets three years for Northampton rape

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Shutesbury Elementary School principal leaving in June after 10 years

Shutesbury Elementary School principal leaving in June after 10 years

Columnist Sara Weinberger: The appalling silence over the atrocities of Oct. 7

Columnist Sara Weinberger: The appalling silence over the atrocities of Oct. 7

High schools: Holyoke boys volleyball sweeps Athol for 5th straight victory (PHOTOS)

High schools: Holyoke boys volleyball sweeps Athol for 5th straight victory (PHOTOS) More history for Tiger Woods. He makes the Masters cut for a record 24th time in a row

More history for Tiger Woods. He makes the Masters cut for a record 24th time in a row Track & field preview 2024: Not happy with last year’s performance, Northampton boys seeking redemption

Track & field preview 2024: Not happy with last year’s performance, Northampton boys seeking redemption Guest columnist William Lambers: Boston Marathon winner inspires action against hunger

Guest columnist William Lambers: Boston Marathon winner inspires action against hunger Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips

Consumer Corner with Anita Wilson: A two-day reprieve in tax filing deadline offers time for tips Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke

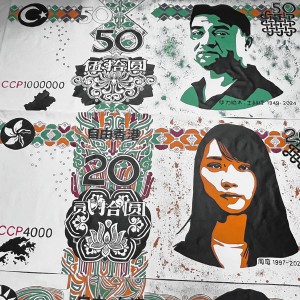

Sublime Systems lands $87M federal award for low-carbon cement plant in Holyoke What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation

What does freedom look like today? On view at Williams College, seven Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin

Book Bag: ‘Dear Oliver: An Unexpected Friendship With Oliver Sacks’ by Susan B. Barry; ‘Benjy’s Messy Room’ by Barbara Diamond Goldin Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back

Only Human with Joan Axelrod-Contrada: To journal or not to journal: Advice for when journaling feels like it’s holding you back Arts Briefs: An arts festival at Smith College, a theatrical version of an iconic 1920s novel, and more

Arts Briefs: An arts festival at Smith College, a theatrical version of an iconic 1920s novel, and more